I should begin, I think, with a distinction: A strong female character is by no means the same thing as a Strong Female Character. The former is well-written and important to the story and the latter is, frankly, a mess we could all live without.

The distinction lies in the modifier “strong.” If a woman is a strong female character, she’s three dimensional and well-developed, with occasional moments of weakness and poor judgment that all human women are, in fact, subject to. Her writing is strong, perhaps even stronger than her constitution as a character. A Strong Female Character (SFC for brevity’s sake) has only one (often poorly written) character trait—strength—driven to such an extreme that nothing else about her character has any room to grow at all.

Hollywood likes writing Strong women and then patting themselves on the back for how equitable they’re being. My preferred example of this is Gazelle (a name I had to look up because it’s so briefly mentioned in the movie that I straight-up forgot it) from “Kingsman: The Secret Service.” As SFCs go, I’ll concede that she isn’t the absolute worst. She isn’t in the movie as a love interest, and her status as a double amputee is never discussed as or considered a liability, but is instead turned into an admittedly badass asset.

That said, I found this clip that introduces her explicitly as “the sexy assassin,” and ultimately, that’s all she is. She kills people and looks rad doing it, but she has no character outside of that. The director says at one point in the video that in the comic’s version, this character was a man, and he changed it to a woman because he thought, again, that it could be sexy. Not that the change would add an interesting layer to character interaction or to the narrative, but that it would add sex appeal. Yay Hollywood.

(Also, the literature major in me is eternally annoyed that her name is Gazelle. I know what they were going for—she’s agile and graceful, yes, like a gazelle—and the argument could be made that that’s not her real name, but the connotations of having her named after an animal and not something with a little more dignity leave a bad taste in my mouth. But I digress.)

I could keep going on about this one SFC and the never-ending list of ways she’s not as feminist as the movie-makers would like to make her out to be, but she’s not the point of this article. She does enumerate the point rather nicely though, which is that giving female characters traditionally male characteristics does not make them inherently strong.

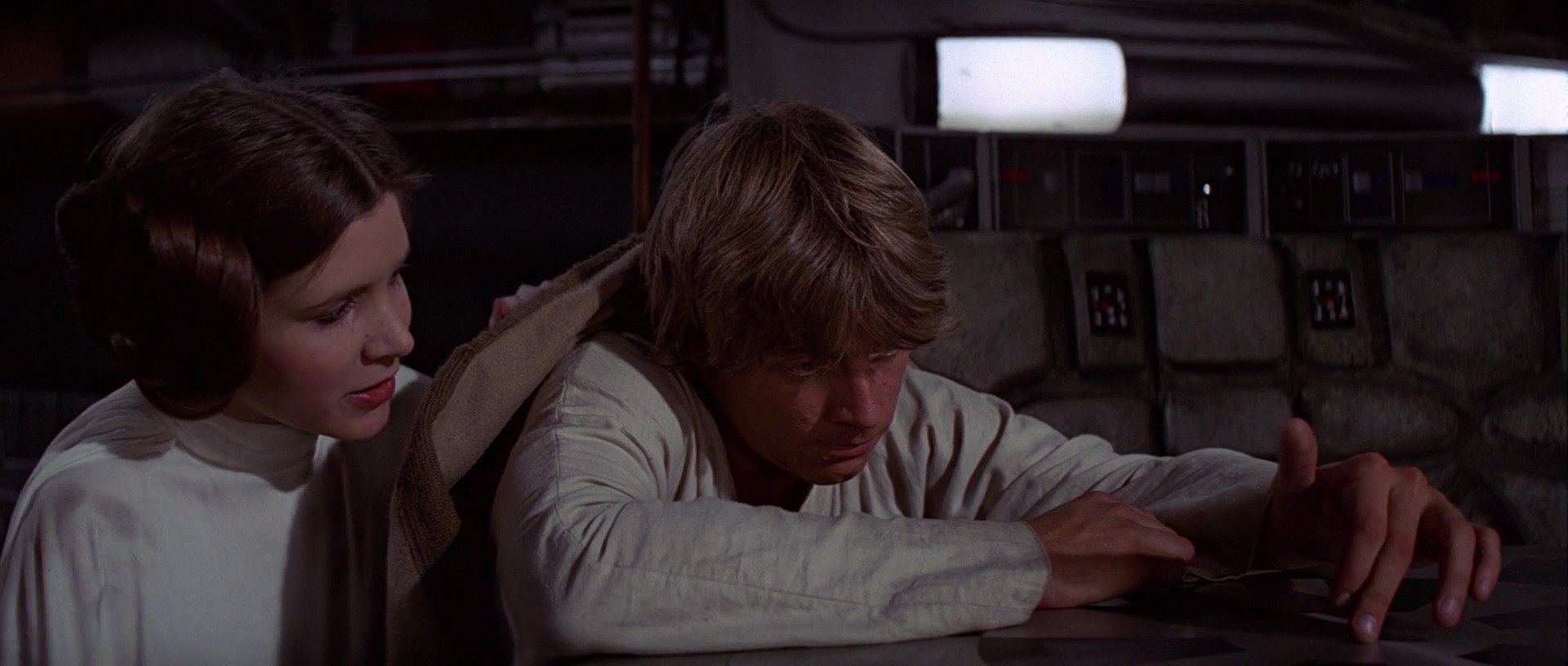

The SFC is not, at this point, as subversive as she might have been at the early points of her existence. She’s everywhere—Black Widow in the Marvel Universe, Princess Leia in “Star Wars,” just to name a few—and her writers think that because she’s physically strong, she doesn’t need anything else. Black Widow has a background with incredible potential that remains continually untapped, and Princess Leia watches her home planet and everyone she knows be destroyed only to comfort Luke about Obi-Wan moments later.

My problem with these characters and others like them is not that they are physically strong or stoic at times, but rather that they have no other depth. They are never allowed to be anything other than physically strong or stoic. Leia is given no time to grieve for her family and her planet because were she to do so, she would be written off as typically feminine and weak.

Still far from the ideal but creeping closer are the women of “Game of Thrones.” I have a lot of problems with what the show has done with their development (I have a lot of problems with a lot of things, if you haven’t caught that drift already), but I also have a lot of good things to say about their original writing in the novels (see, I can be a pleasant person).

In two separate interviews I found among the apparently millions he’s done, George R.R. Martin unceremoniously professes to being a feminist (here and at around eighteen and a half minutes here, if you’ve got time to kill and want to read/hear some genuinely interesting conversations), and that belief shows in how he writes his female characters.

They aren’t all likable—some aren’t likable at all—but they are, I think, realistic. They are strong, some physically and some mentally, and smart and capable, but they are also flawed. They make bad decisions and mistakes, and that’s okay. Nobody is all one thing all the time, and even women who are badass have moments of weakness. To think and to write otherwise is just untrue.

I’m excited, now, when I see women cry on screen or admit to other characters that they need help or that they aren’t perfect. These are things that real women do; for women to do them in media is not unrealistic and not, I think, a very high bar for the writers to be meeting. Big time writers have no problem writing men who are interesting and well-developed, but for some reason (*cough sexism cough*) those same writing skills aren’t extended to their female counterparts.

I feel like I’m simultaneously asking for too much and too little, which is, of course, ridiculous. Experiencing women in media who are badass in all the ways women can be should be the only way they are experienced. With that said, I know how slow Hollywood is to change, and I also know that women are being given new and exciting chances in film, and I’ll take Strong female characters over no female characters any day.

Bravo. So many people seem so enraptured by SFCs that they don’t notice the problems you point out. Hopefully we will see more of the strong female characters you want to see, which I also want to see.

[…] https://studybreaks.com/2016/09/21/why-the-strong-female-character-doesnt-represent-real-women/ […]