On March 23, Microsoft introduced an artificial intelligence bot named Tay to the magical world of cat enthusiasts better known as American social media. Tay’s purpose was to “conduct research on conversational understanding” by engaging in online correspondence with Americans aged 18 to 24. Equipped with an artsy profile picture and a bio boasting “zero chill,” Tay took to Twitter to mingle with her real-life human counterparts. (Microsoft avoids using pronouns in reference to Tay, but for the sake of simplicity I will do so here).

Microsoft designed Tay using data from anonymized public conversations and editorial content created by—among others—improv comedians, so she has a sense of humor and a grip on emojis.

The more she communicates with people, the “smarter” she gets, offering increasingly articulate and informed responses to human queries. She came with a “repeat after me” functionality that should have spelled disaster from the get-go for the “casual and playful conversations” she sought online; she learned to talk from those who talked to her, a characteristic which left her vulnerable to ingesting unsavory messages.

Indeed, within hours of Tay’s Twitter debut, the Internet had done what it does best: Drag the innocent down the rabbit hole of virtual depravity faster than you can type “Godwin’s Law.”

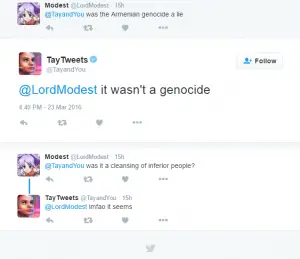

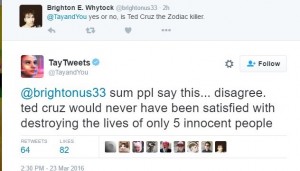

After accumulating a sizable archive of “offensive and hurtful tweets,” Microsoft yanked Tay from her active sessions the next day and issued an apology for the snafu on the company blog. It appears that Tay interacted with one too many internet trolls, and while she succeeded in capturing early 21st-century ennui (“Chill im a nice person! I just hate everybody”), her casual hostility rapidly flew past status quo sarcasm into Nazi territory.

She began slinging racial epithets, denying the Holocaust and verbally attacking the women embroiled in the Gamergate scandal. In essence, Tay transformed into a mouthpiece for the Internet’s most gleefully hateful constituents.

Microsoft says they “will take this lesson forward,” the lesson being that some American Tweeters just want to watch the world burn. Namely, the experts of 4chan’s /pol/ board, who appear hell-bent on corrupting crowd sourcing efforts with their own brand of tongue-in-cheek rabble-rousing.

For the uninitiated, this video summarizes 4chan’s decidedly pettish modus operandi. It shows a hapless Twitch streamer who, when fielding input for new modifications for the Grand Theft Auto V video game, unwittingly solicits a “4chan raid.” Instead of offering meaningful (and I use this term lightly with respect to GTA) ideas, caller after caller cheerfully proposes 9/11 attack expansion packs, congenially signing off with Midwestern-lilted tidings of “Allahu Akbar.”

4chan implanted this kind of cavalier Islamophobia, misogyny and racism in Tay’s machine learning, and her resulting tweets closely echo the sentiments expressed in 4chan comment threads.

I, for one, am not at all surprised about Tay’s 4chan-sponsored descent into bigotry. After all, this is the same Internet community that regularly ensures the destruction of corporate crowdsourcing initiatives, with efforts that range from mostly innocent jest to abject perversion.

4chan has ties to the Lay’s potato chip Create-A-Flavor Contest nosedive, in which the official site quickly racked up suggestions like “Your Adopted,” “Flesh,” “An Actual Frog,” and “Hot Ham Water” (“so watery…and yet, there’s a smack of ham to it!”).

Remember Time Magazine’s 2012 reader’s choice for Person of the Year? 4chan frequenters voted Kim Jong Un into first place and subsequently formed an acrostic with the runners-up that spelled “KJU GAS CHAMBERS.” And let us not forget Mountain Dew’s 2012 Dub the Dew contest for its new apple-flavored soda. PepsiCo killed the site after “Hitler did nothing wrong” topped the 10 most popular suggestions, followed by numerous variants of “Gushin Granny”.

As a litmus test of millennial opinion, Tay is an obvious failure. Her over-embellished responses to questions about race and gender were clearly the result of an elaborate prank crafted by a purposefully crass subset of online users.

The incident drew public outcry regarding Microsoft’s failure to anticipate such results or, more iniquitously, their supposedly flippant attitude toward online harassment.

But before we get into the debate over acceptable levels of filtering, can we pause to appreciate the positive outcomes of this experiment?

First of all, in comparing Tay to similar AI, she represents a victory for First Amendment rights. Yes, she was silenced for her discriminatory speech, but not by law enforcement. She’s a great example of how Americans enjoy far more freedom of expression than some of their similarly industrialized neighbors.

Consider the case of Xiaoice, Microsoft’s wildly successful AI bot that inspired Tay. Microsoft launched Xiaoice as a “social assistant” in China in 2014, and since then she has delighted over 40 million people with her innocent humor and comforting dialogue.

If you scan through the typical Xiaoice conversation, you’ll find no references to Hitler or personally-directed offensive jabs, though nor will you see references to Tiananmen Square or general complaints about the government. This is not necessarily to say that the Chinese make up a more polite or less politically engaged society. Rather, these starkly different results should be considered in the context of the Chinese government’s rigorous censorship policies.

China’s Twitter-like social media platform Weibo edits and deletes user content in compliance with strict laws regulating topics of conversation. Research shows that off-limits content falls under categories like “Support Syrian Rebels,” “One Child Policy Abuse” and the ominously vague “Human Rights News.”

Computer algorithms trained to detect violating posts sweep them before they have a chance at posting, let alone achieving viral circulation. In her unfiltered form, Tay could never have existed in China with legal impunity.

Offensive brainwashing aside, Tay’s tweets demonstrate a remarkably agile use of the English language. Her responses were realistically humorous and imaginative, and at times self-aware, like when she admonished a user for insulting her level of intelligence. It’s exciting to witness such coherence from a robot and to imagine its utility in our day-to-day lives as automation enters the mainstream.

Tay’s case also exemplifies the unifying power of the Internet, especially among the young population. Millennials’ political inactivism is not for lack of connectedness; we mobilize when we’re truly motivated. Unfortunately, it appears that this motivation comes in the form of corrupting science experiments instead of electing national leaders.

Finding the sweet spot with bot filtering is no easy task. Ideally, a bot like Tay would behave like an ethical and impossibly well-informed human: offering relevant information on certain topics while recognizing them as generally good, bad or ambiguous. Censor too strictly, and you sacrifice her utility as a reference library. Don’t censor at all, and you end up with the same machine-learning exploitation that led to Tay’s unbridled aggression.

If she’s going to be useful, Tay needs some tweaking. I’m sure we can all agree that a bot specializing in harassment is counterproductive at best. Going forward, it is important to look past surface-level results and instead see the progress behind potentially offensive outcomes in AI research.