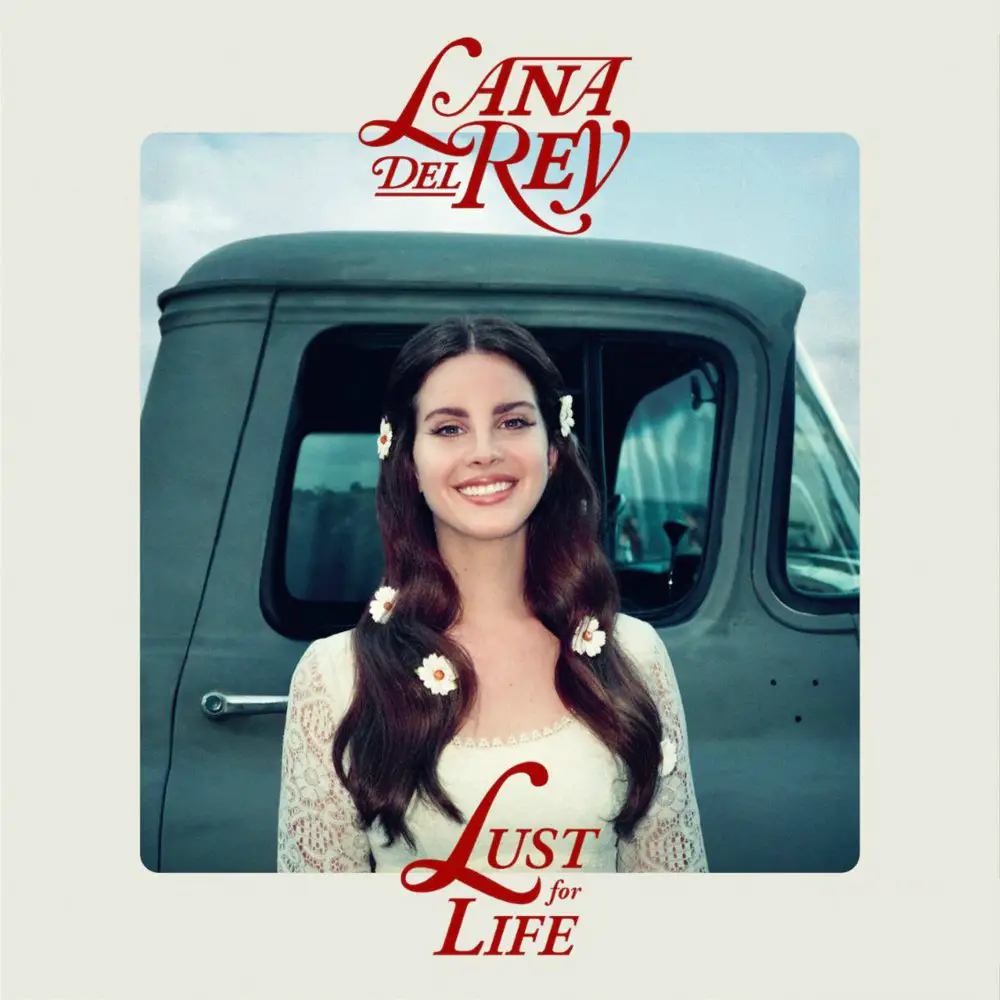

Lana Del Rey’s persona has been carefully crafted over the span of four albums, each with a cover featuring a portrait photo vaguely Californian in setting, an automotive vehicle and defiant block text. Her album titles are either melancholy—“Born to Die” and “Ultraviolence”—or idealistic—“Paradise” and “Honeymoon.” The subject matter of Del Rey’s songs rarely strays from dangerous love, drugs and all things Americana. As a result, her work is formulaic.

As a listener, I felt lost in the layers of cultural allusions and repetitive themes. The real Del Rey was enigmatic; the lines between the real and imagined were blurry. I was a big fan of “Born to Die,” but stopped following Del Rey after “Ultraviolence” was just more of the same.

A Change in Attitude

However, the lead single for “Lust for Life” promised something new. “Love” relied on sonic standbys for Del Rey, but for the first time ever, she sounded hopeful and energetic. Moreover, the song was a direct address to her listeners: “Look at you kids with your vintage music / coming through satellites while cruising / You’re part of the past, but now you’re the future.” “Love” tore down the confines of the universe that Del Rey had occupied and brought her sound to an accessible real place—a triumphant, creative step forward.

The fifth full-length album clocks in at seventy-two minutes with sixteen songs. As usual, the folds of symbolism stack and stack; she references the Manson Murders, Old Hollywood, Motley Crue, Frank Sinatra—all on one cut. Some symbols are more well integrated than others: a nod to The Angels’ “My Boyfriend’s Back” sticks out too much, while the inversion of a verse from Neil Young’s “My My, Hey Hey” adds depth and complexity.

Behind the allusions, “Lust for Life” does offer some insights into Del Rey’s new outlook. Happiness radiates from this album, particularly on the chorus of the eponymous track: “A lust for life / keeps us alive.” The chant is anthemic and effervescent, a one-eighty from the chorus of the title track on her first album: “’Cause you and I / we were born to die.”

Disappointingly, some cuts are depressive and reminiscent of the previous Del Rey persona. On an album that is supposed to be about growth, singing “I was such a fool for believing that you / could change all the ways you’ve been living / but you just couldn’t stop” detracts from that goal.

The Rap Interlude

“Lust for Life” suffers from poor organization and some imbalanced, awkward production. Foremost, the progression of the album is confusing—the first five tracks are standard Lana Del Rey fare, with a feature by The Weeknd, but then the album makes a sharp pivot into a three-cut, swaggering interlude.

For a work that seems primarily concerned with interpersonal reflection and solidarity, “Lust for Life” is carrying extra weight as it tries to balance Del Rey’s classical, timeless sound and elements of trap and hip hop. “Born to Die” did so seamlessly, so the lack of coherence here is perplexing.

The results are convoluted, foreign to the album’s raison d’etre. The confusion detracts from Del Rey’s control over the album, which is further hampered by back-to-back A$AP Rocky features on “Summer Bummer” and “Groupie Love.” Even after Del Rey told Billboard that “Lust for Life” would turn in a different direction than her previous albums, this chunk of trip hop is loyal to the previous themes of “Born to Die,” “Ultraviolence” and “Honeymoon.”

“In My Feelings,” the final track of the interlude, boasts Del Rey rap-singing “Who’s doper than this bitch? / Who’s freer than me?” It’s half-cool, half-awkward to see Del Rey talk herself up like this and take an active role as a speaker in her own music.

God Bless America (and Lots of Other Stuff, Too)

“Lust for Life” jettisons the rap halfway through the album to open an elaborate, heavy-handed ode. Five songs, with emo-length titles, are devoted to Del Rey’s attitudes toward America. She attempts to grapple with monumental ideas—nuclear war, the empire and decay of America, love—but ends up saying little of substance. All of these themes require length and effort to completely flesh out, and breezing through them in five tracks is negligent.

However, the tribute does have some strong moments. “Coachella – Woodstock In My Mind” places Del Rey in a real location and offers some ground for an artist whose work has been so reliant on historical reference. The song opens with a bassline that submerges the listener, as if they were standing with her watching Father John Misty. The verses on this track are sincere— “I’d say he was hella cool to win them over / critics can be so mean sometimes”—another element of emotion that can be lost in the floatiness of Del Rey’s discography.

The features on this leg of the album, Stevie Nicks and Sean Ono Lennon, make a larger contribution to the work. Both of their songs are charming, xx duets that touch on the sounds from Fleetwood Mac and The Beatles, respectively. She performs well accompanying these two artists, but it’s another case of Del Rey being overshadowed on her own album.

Lust Ends

While “Lust for Life” does lose its footing as it unravels, the final three songs return to the album’s apparent themes of growth. From Del Rey’s beaming visage on the sleeve to the positive valence of the title, the artist has had a change of heart. “Heroin,” instead of being another song that glorifies substance, like “Yayo” or “Florida Kilos,” uses the drug as a vehicle to express remorse over using. When she croons “I hope that I come back one day / to tell you that I really changed, baby,” it sounds like she is speaking from the heart.

“Heroin” turns to “Change,” which is a bare piano ballad, abandoning stylishness for honesty and heart. The pair of the soft, clear sounds of the piano and Del Rey’s gauzy, airy voice is a perfect match. The lyrics are free of reference and almost holy, as if the artist were grasping at divinity and forgiveness, especially at the refrain: “Change is a powerful thing, people are powerful beings / Trying to find the power in me to be faithful.” Del Rey sheds the guise of American culture obsession and lets herself be, and the product is some of her best work.

The ultimate track, “Get Free,” is the perfect send-off for an album that is about freeing yourself from the chains of your past. As if she were the solo star of a ’60s girl-group, sedated and washed in reverb, Del Rey sings, “Finally / I’m crossing the threshold / from the ordinary world / to the reveal of my heart.” Other attempts at this style on the album are too aggressive (“shut-up” and “bitch”) to be loyal to the vintage sound, but the energy shines through here.

While Del Rey struggles to arrive at her point, the emotional release at the end of “Get Free” signals a movement within the artist for the betterment of herself—and even the world. It’s a lesson we could all learn again.