In light of its 10th anniversary — and considering his recent Super Bowl performance alongside hip-hop legends Dr. Dre, Snoop Dog, Eminem, Mary J. Blige and 50 Cent — now seems like a good time as any to go over Kendrick Lamar’s groundbreaking album “good kid, m.A.A.d. city.”

“Good kid m.A.A.d city,” subtitled, “a short film by Kendrick Lamar,” is a concept album with a nonlinear Tarantino-like plot structure that spans one pivotal day in Kendrick’s teenage upbringing in the streets of Compton.

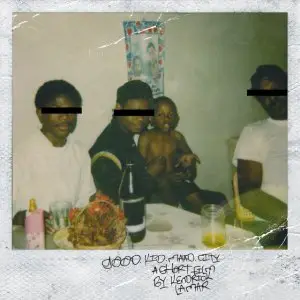

For the album’s cover art, Kendrick used an actual family polaroid of himself as a young boy sitting with family members around a small kitchen table. His uncle holds little Kendrick with one hand and flashes a gang sign with the other. Regarding the album’s cover, Kendrick stated, “It’s really just like a self-portrait. I feel like I needed to make this album to move on with my life… It was a venting process to tell the stories I never told. That photo says so much about my life and about how I was raised in Compton and the things I’ve seen just through them innocent eyes. You don’t see nobody else’s eyes, but you see my eyes are innocent and trying to figure out what’s going on.”

The album begins with the track “Sherane a.k.a Master Splinter’s Daughter” and serves as a flash-forward into the middle of the story. Kendrick, a sophomore in high school, has borrowed his mother’s van to drive outside Compton to Paramount to hook up with Sherane, a girl he met at a party. Although Kendrick knows her cousin is a gangbanger, youthful lust overpowers his intuition and puts Kendrick in danger as he pulls up to Sherane’s house. Two men in black hoodies, who are assumed to be gang-affiliated, approach Lamar and the song ends abruptly — a cliffhanger.

The album’s narrative doesn’t advance with the next track, “B*tch Don’t Kill My Vibe.” Here, Kendrick observes his place in the music industry — the new people around him trying to exploit him and his mission to elevate the current state of hip-hop. The track ends with a skit where Kendrick’s friends pick them up in a Toyota. They drive around Compton freestyling over an instrumental beat CD over the album’s next track, “Backseat Freestyle.” Here, Kendrick is rapping as he did at age 16. The story’s true beginning is a group of young kids driving around the city looking for trouble.

The next song on the album is “The Art of Peer Pressure.” The genius of this song is the way Kendrick advances the narrative with detailed accounts of his friends’ antics while also engaging in deep self-reflection about those actions. He does this with a recurring phrase at the end of each verse: “until/cause I’m with the homies” — acknowledging that his actions are out of character, but he does them anyway due to his friends and the environment around him. He’s a “good kid” in a “mad city.”

“Money Trees,” the album’s next track, recaps the story so far, presumably while Kendrick is under the influence and driving to Sherane’s house. As Kendrick gets closer to his destination, he begins lusting over Sherane on the album’s next song, “Poetic Justice.” At the song’s conclusion, the narrative picks up where Kendrick left it on the opening track, “Sherane.”

The following two songs, “Good Kid” and “m.A.A.d. city,” are the album’s fulcrum. They mark the beginning of Kendrick’s transformation from “K. Dot,” an impressionable boy whose actions are controlled by his environment, to “Kendrick Lamar,” a self-realized enlightened adult. Each of the three verses of “Good Kid” focus on different environmental influences that threaten a good kid in a place like Compton. Verse one speaks on gang culture and the dangers of maneuvering throughout the city without an affiliation.

While “red and blue” in the first verse reference the Bloods and Crips, Kendrick uses the same colors in verse two, only this time to refer to police sirens. He draws a parallel between getting jumped by gangs and being racially profiled by cops. Verse three focuses on the only escape available to a kid in a city surrounded by gang violence and police brutality: drugs and alcohol. He describes these vices as “silence from the violent rhythms of the street” and sympathizes with those who fall victim to it, knowing the temptation of relief it brings.

The track “m.A.A.d. city” expands on the themes in “Good Kid,” though its tone is more immediate, frantic and hysterical. In verse one, Kendrick describes some of the brutal scenes he witnessed growing up, and the line “Pakistan on every porch” likens Compton to a war zone. He raps in a tone of desperation, like a man on the verge of a breakdown. The stories he tells are true, so much so that Kendrick bleeps out the names as not to incriminate anyone.

After repeating the hook and bridge, the song suddenly transforms without warning, switching from the frenetic driving energy of the first verse to a bouncing classic West Coast sounding beat. When Kendrick begins to rap in verse two in the same panic-stricken voice as in verse one, the listener realizes reality is no different. Compton is a nightmare you can’t wake up from. He continues the stories about his experience in this “mad city.”

Kendrick follows with one of the most impactful verses on the album, where he wonders if his audience will stay loyal to him after confessing his sins on record. If so, can the “good kid” become the prototypical model for boys like him to escape the violent cycle of street life? For a good reason, Kendrick says, “Compton, USA,” not “Compton, California.” Kendrick’s experience is part of the American experience — a haunting reality for millions of Americans. It’s also a reality lost in the romantic perfumes of the American Dream, often marketed in political speeches and national rhetoric.

With “good kid m.A.A.d city,” Kendrick is putting a face to the American Dream. He’s a success story, yes, but he refuses to gloss over his past in favor of his present. It provides detailed accounts of his experience and, by proxy, millions of others like him. Kendrick follows “Compton, USA” with the phrase “made me an angel on angel dust” — me, Angel, Angel, dust. Kendrick argues that he, and perhaps all of us, are born pure-born angels, and the things we do are sometimes impure, especially when heavily influenced by the environment we inhabit. But in our hearts, we remain pure.

This transitions into the song ‘Swimming Pools,” the album’s hit single. In it, Kendrick explains his complex relationship with alcohol. He describes a group in a house with so much alcohol that it can fill a swimming pool. He began drinking only because of peer pressure and expands upon the idea outlined in the third verse of “Good Kid.” The skit at the end of “Swimming Pools” sees Kendrick’s friend “Dave” shot and dying in his arms.

The skit is immediately followed by the somber opening phrases, “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst.” The song confronts the repercussions of the horrors of Compton street life — the dead, and the living that mourn the dead. Kendrick responds to the characters he portrays in verses one and two, saying, “I count lives all on the songs / look at the weak and cry, pray one day, you’ll be strong / Fighting for your rights even when you’re wrong / And hope that at least one of you think about me when I’m gone.”

On the skit that bridges “Sing About Me” with “I’m Dying of Thirst,” Kendrick’s friends reach a breaking point. They stand now in front of a store, panic-stricken, angry, frustrated and wanting to seek revenge for their loss. Finally, Dave’s brother snaps, screaming, “I’m tired of this s***,” implying he’s tired of the fatal cycle of death and retaliation. “I’m Dying of Thirst” is a sprawling continuous verse broken up by the refrain “I’m dying of thirst” repeated three times.

He opens the song with the line, “I’m tired of running / tired of hunting my own kind / retiring nothing.” Kendrick and his friends are exhausted by the cyclical nature of death and retaliation but know no other way to live. Kendrick continues the song with multiple vignettes of Compton’s reality, further emphasizing the frustration of being unhappy yet not having the resources to change. The cure for “the thirst” is revealed in the skit that follows “I’m Dying of Thirst.”

A woman leads the boys in the sinner’s prayer, the Christian prayer recited by those who feel the presence of sin and desire a fresh start to a relationship with God. This marks the beginning of Kendrick’s transformation and leads into the penultimate track, “Real.”

In “Real,” Kendrick celebrates knowing and loving one’s authentic self outside of one’s environmental influences. In verses one and two, the characters represent Sherane and women like her in the neighborhood, and Kendrick’s homies represent men like him. He calls out the lifestyle these characters seem to love: clothes, cars, money, drama, violence, and ends both verses with the same refrain: “What’s love got to do with it when you don’t love yourself.” In verse three, Kendrick asks himself if he should hate these things for falsely filling a void in him and stifling his personal growth. He is searching for a resolution between his love and his resentment for Compton.

The answers come by way of a voicemail from Kendrick’s parents, which is cut in the song after the third verse. The harmony created by the emergence of these two worlds, song and skit, which were up until this point sonically separate, is incredibly impactful and moving. Kendrick’s father tells him “real” means responsibility, family and God. Kendrick’s mother tells him that she hopes he learns from his mistakes and comes back as a man. She encourages Kendrick to take his music seriously and give back to his community by giving them hope and showing them that he could rise out of a dark place and become a positive person.

Sounds of the tape being either rewound or fast-forwarded signifies the end of the “good kid, m.A.A.d. city” narrative. Kendrick has found resolution through his parents’ advice and is prime to move forward in life positively and give back to his community through music and leadership.

Following the sound is this song “Compton,” a celebration of the city and Kendrick’s first collaboration with his hometown hero, Dr. Dre. With this in mind, the tape sound can be interpreted as a fast forward from the 16-year-old Kendrick portrayed on the album to the present 25-year-old Kendrick, who collaborates with Dre. The content of the song reinforces this interpretation. It’s an upbeat, cheerful celebration of the city, similar to the kind of music Kendrick’s mom asked him to make in the final skit.

“Good kid, m.A.A.d. city“ is a complex, deeply personal coming-of-age story full of honesty in a genre not known for vulnerability and from an artist whose origins do not always lend themselves to introspection. It would go on to solidify Kendrick’s place and influence in the world of hip-hop as a whole. It managed to be that unique work that achieved popular success without compromising artistry.

The album was met with universal critical acclaim from hip-hop and pop media outlets. Many credible publications named it the album of the year. It was nominated for five Grammy awards, won album of the year at the 2013 BET awards, went certified platinum in less than a year and catapulted Kendrick internationally to world stardom.

Of course, for the reserved and analytical Kendrick, ever aware of his influences on his environment, the transition to stardom was not easy. He was transplanted from a “mad city” ruled by temptation and vice into another kind of world also filled with temptation and vice. The end of the album sees Kendrick celebrating his escape from a tumultuous life, shedding the influence of his environment and bringing hope and joy to his community by telling their story through his music.