What does it mean to be genderqueer? Genderqueer is a word with boundless gender possibilities and rich history. As writer and activist Jacob Tobia notes in his Inqueery video about genderqueer’s history, for the past 25 years, the word has been an inclusive term that refers to individuals whose identities exist beyond the binary. It can be an umbrella term for “anyone between or outside male and female, refer to anyone who exists between the two and those who identify as a third gender” — genderfluid, androgynous, two-spirit, pangender and agender, just to name a few. The need for an all-inclusive term that went beyond typical gender binary categories gained momentum in the late 1980s and early 1990s — relatively recently, when queer and transgender people were challenging ideas about gender and sexuality in their writing and activism.

This recent convergence on an inclusive term for identities that exist beyond the binary was transformational for Maia Kobabe. Kobabe, who uses the pronouns e, em and eir, was born in 1991, when the term genderqueer was in its infancy. Without a clear term to match Kobabe’s gender identity, eir path to self-identity was an uphill battle. As Kobabe grew up, genderqueer become a term cemented by its use in writing by genderqueer, nonbinary and transgender figureheads. Today, youth finally have a safe space and a word that accurately aligns with their respective gender identities and sexualities. I call that progress!

Before looking at Kobabe’s revolutionary graphic memoir, “GenderQueer,” it’s essential to note Kobabe’s pronouns. Kobabe goes by the Spivak pronouns: e, em, eir, eirs, emself. Although not in widespread use, Spivak pronouns are a perfect solution for those who feel that the standard “he/she/they” pronouns do not fit them, which was Kobabe’s case exactly. As Kobabe notes in eir graphic memoir, as soon as e discovered these pronouns, e felt “the biggest tingle down [eir] spine.” This reaction perfectly describes how comforting it is to discover pronouns that accurately fit and depict one’s gender identity.

Kobabe, a graduate of the first-ever class of the MFA Comics Program at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, has been self-publishing comics and zines since 2010. Before writing “GenderQueer,” e dappled in fan fiction, eir favorite genre, but purposely strayed from writing about eir gender in any way, shape or form. Kobabe’s short comics have been featured in TheNib and anthologies like Mine!, Gothic Tales of Haunted Love, The Secret Loves of Geeks for years before the success of “GenderQueer.” Ironically, Kobabe was originally terrified to write a memoir, despite eir edifying journey; Kobabe simply didn’t think that e could bring eirself to share the deepest, darkest, most emotionally-charged intricacies of eir life.

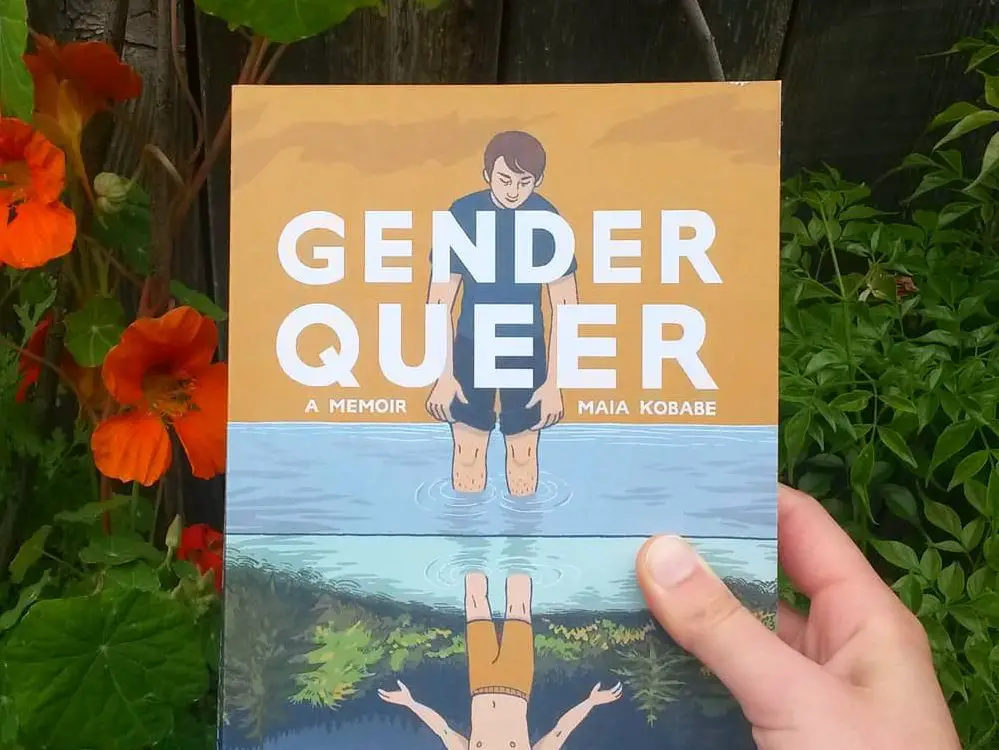

Kobabe toppled this fear, though, with eir graphic memoir, “GenderQueer,” which details Kobabe’s cathartic journey to identifying as nonbinary and asexual. “GenderQueer,” which has attracted a large fanbase that ranges from young adult and college-aged readers to adult readers alike, follows Kobabe’s life, from eir childhood to eir adulthood. “GenderQueer” explores themes such as adolescent confusion with gender, sexuality and crushes. In addition, the book notes how Kobabe grapples with coming out to both eir family and society as a whole. Along with these pervasive themes, Kobabe gives us a glimpse into eir personalized stories and quirks, such as eir love of gay fan fiction, nature, snakes, drawing, fandom and, not shockingly, comics. “GenderQueer” also delves into the trauma Kobabe felt in relation to eir period, breasts and pap smears, which all felt like a violation and contradiction to eir gender identity.

Kobabe’s chosen medium, graphic memoir, is perfect for advancing the message e is attempting to convey to eir readers. As the clichéd saying goes, “a picture is worth a thousand words,” and in the case of “GenderQueer,” this couldn’t be more accurate. When Kobabe attempts to explain eir conflicting, charged emotions, eir graphics solidify the emotions that e is trying to get across.

One clear example of how eir graphics enhance the book’s message is evident when e compares the trauma of eir pap smear to being “stabbed through [eir] entire body” and how “with this came a wave of psychological horror at the realization that things go inside [eir] body” (128). Kobabe includes a graphic visual of eirself being stabbed in the vagina, while e is painfully bent over with eir hand over eir face; this image is coupled with a white background, which allows for complete focus on the horrifyingly painful image. With this graphic, readers get a visual of how traumatizing pap smears are for Kobabe, in a way that words could simply not convey.

Another clear example of how graphics enhance Kobabe’s message is eir use of nature, such as night and day and landscapes, to send salient messages about eir gender identity. The most significant example of this is when Kobabe distinguishes between the mountains, forest and sea to compare gender to a landscape, where “some people are happy to live in the place they were born, while others must make a journey to reach the climate in which they can flourish and grow” (191). In the beginning of eir graphic memoir, Kobabe compares eir gender to an unambiguous scale. This shift from comparing gender to a harsh scale (of give and take) to an all-encompassing landscape shows Kobabe’s growth in self-discovery and identity.

Without these images to accompany Kobabe’s graphic memoir, readers would not be left with the lasting, powerful image that accurately displays the way Kobabe views and feels gender identity. These images give a further glimpse into Kobabe’s personal experiences. They allow readers to fully empathize and put themselves in Kobabe’s shoes, enabling an understanding deeper than a typical novel.

“GenderQueer” is more than just Kobabe’s personal story. It’s an emotionally moving guide for advocates, friends and readers everywhere on gender identity — what it means and how to think about it. “GenderQueer” is a contemporary example of genderqueer writing that seeks to enlighten others about a personal experience about the discovery of one’s gender identity — in Kobabe’s case, eir nonbinary and asexual identities, and in a broader sense, the challenges that LGBTQIA+ individuals face, from their infancy to their adulthood. With “GenderQueer,” Kobabe is broadening horizons and transcending barriers to provide readers with a modern depiction of what it means to be genderqueer.