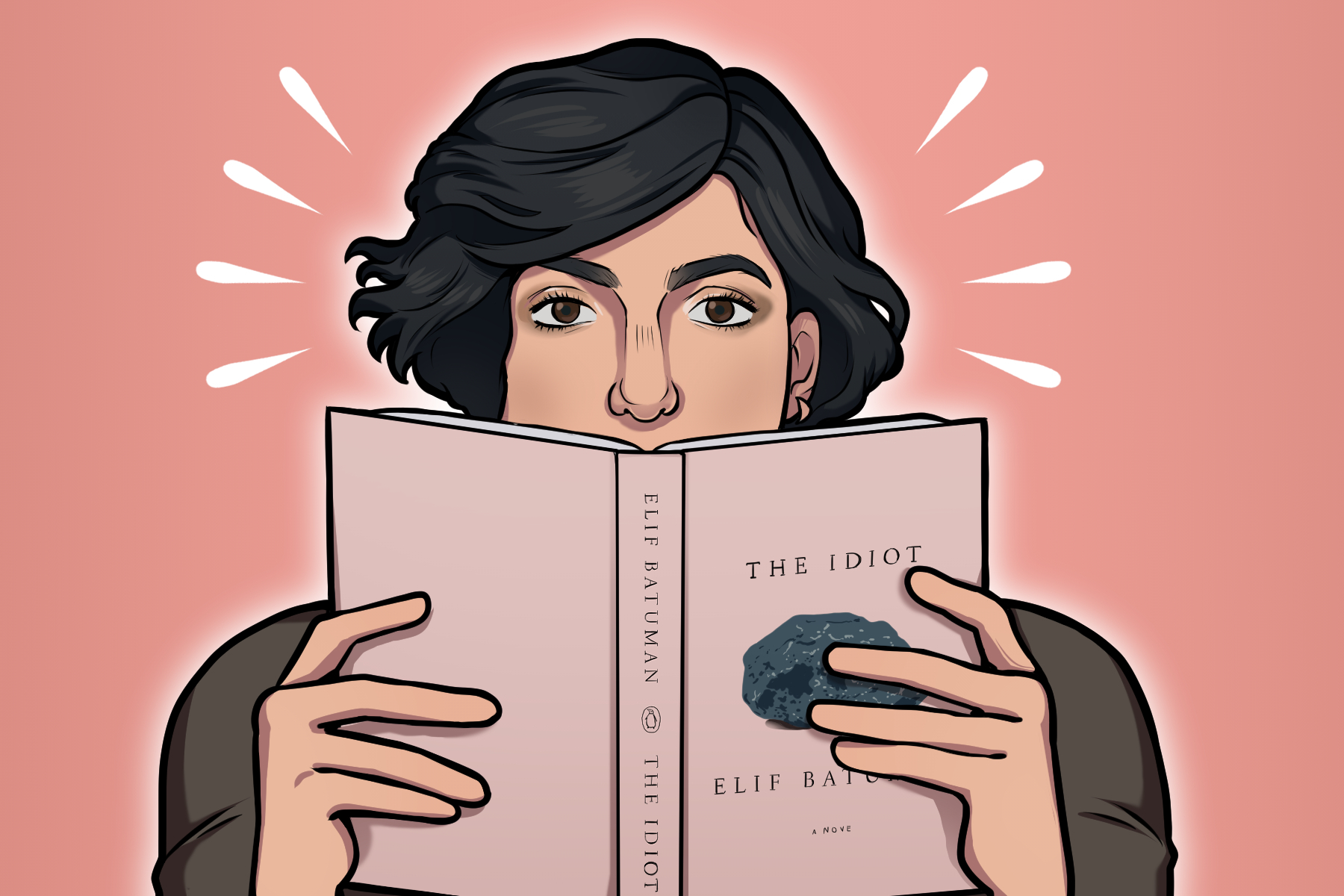

If you read the blurb on the back of Elif Batuman’s 2017 debut novel, “The Idiot,” you’ll see the book described as “a heroic yet self-effacing reckoning with the terror and joy of becoming a person in a world that is as intoxicating as it is disquieting.” I’d like to meet whoever wrote this surprisingly lucid yet appropriately vague description and congratulate them on capturing such an elusive story so perfectly. Batuman wrote a novel that is not easy to pin down.

Set in 1995, “The Idiot” follows Selin, a brainy Turkish American, through her first-year experience at Harvard and abroad. Its loose, almost leisurely plot largely revolves around Selin’s unusual relationship with a student from Hungary, a senior named Ivan. The pair exchange emails featuring some of the oddest ideas and phrases I’ve ever come across in fiction, ones so absurd that I wondered how on earth Batuman came up with them.

“Either/Or,” the sequel that picks up almost right where we left off with “The Idiot,” finds Selin navigating her second year at Harvard. At the beginning of the story, she reels from her last encounter with Ivan and doubts everything she thought she knew about him. Fortunately — or unfortunately, depending on your perspective — the sequel features far less of Ivan and a more invigorating cast of characters, though Ivan is still very mentally present in Selin’s life. In one scene that shows off the dark humor of Batuman especially well, a depressed Selin lies in bed, missing class to wallow about Ivan and listen to objectively the best album for the occasion: Fiona Apple’s album “Tidal.” It’s good to see that despite our heroine’s cerebral personality, she is still a teenager, after all.

Odd, maybe-romantic emails aside, the novel and its sequel are mostly composed of Selin’s ponderous monologues and musings. Without getting too heady, Batuman smoothly weaves in deep linguistic concepts and literature as texts Selin must read for class. These works include everything from the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis to the Russian classics, which she always questions dutifully: “Why did Nina have to look into Leonid’s eyes, instead of into the telescope? How did Leonid solve anything? Why did every story have to end with marriage?”

Almost every page features questions like these, valuable simply for being asked in the first place and not for any answers you might come up with. Selin is perhaps the most introspective and inquisitive narrator in contemporary fiction, and this is what makes her so much larger than life and so admirable. While reading “Either/Or,” I noticed that no matter how ignorant, rude or pompous the person she’s talking to is, Selin always considers what they have to say, questioning their words and her reaction to them carefully. Often, she ends up dismissing their thoughts, but only after giving them a chance. How many of us can say we take the time and effort to embody this practice? Certainly not many — including me. It’s not necessarily a display of trust in everyone, but rather, a way of treating everyone like their words may hold merit, no matter what.

This intellectual nobility of hers (a trait I’ve never seen in a fictional character before) was something of an awakening for me. Selin helped me realize that the life of someone dedicated to writing is not just about sitting down to punch out some words, stringing them together into a story and calling it a day. It involves almost every aspect of your interactions with the world and with yourself. You need to cultivate habits that can help you reflect on and notice the small things in your life, to listen eagerly and openly.

Of course, there isn’t just one way to be a writer, just as there isn’t one way to be an engineer, teacher or painter. The writer’s life depends on the individual. But Selin pushed me to consider what kind of writer I want to be and how I can start being them. Through her journeys, she leads readers to look deeper within themselves, to cultivate a sense of wonder essential to every writer. Batuman encourages them to marvel at the absurdities, quirks and charm of people everywhere — whether they’re in the Hungarian countryside or at Harvard Square. Her adventures in these two novels are particularly enlightening and exciting for young aspiring writers who are still early in the process of discovering their personal nook in the world.

“Either/Or,” released in May of this year, gave me the words to describe something I’ve wanted to embody since I was younger, without knowing exactly what it was: the “aesthetic life.” Selin learns this term from Soren Kierkegaard’s “Either/Or,” a philosophical work she finds early on in the sequel. In a scene I’m not sure I’ll ever forget, Selin picks up this book by chance in a bookstore: “‘Either, then, one is to live aesthetically or one is to live ethically.’ My heart was pounding. There was a book about this?” (This scene strikes me as a little funny now, seeing as Kierkegaard’s “Either/Or” has been downright impossible to find in any bookstore I’ve been to.)

From then on, this notion of an “aesthetic life” (more of a subjective sensibility than a rigid term) informs much of Selin’s thoughts and reflections within “Either/Or.” She’s able to identify with this somewhat Romantic worldview, despite it seeming to have disintegrated into a mere relic of classic novels over the last century or so. But thankfully, Batuman revives it, answering the calls of every young writer or artist who, like me, retreats to the world of aesthetics when everything becomes too much. She writes for those who daydream about traveling to new places, meeting strange and fascinating people, scribbling anecdotes in a little notebook and writing up stories in the evenings.

For anyone who’s indulged in these ideas, aspiring to live freely and lightly the way Selin does, her odyssey will revitalize you, move you and push you to rethink how you go about each day. I know that after finishing “The Idiot” and “Either/Or,” I hesitated each time I was about to make a hasty judgment about something or reach for my phone without needing to. Selin inspired me to question my own actions and thoughts before I let them define me; every writer should at least consider this mode of being as a personal practice.

I can’t guarantee that everyone, including writers, will enjoy Selin’s introspective tendencies or relate to her inquisition of the world around her. Even I found her questions a little too incessant at times. Every once in a while, I asked myself, “Does this person ever turn her brain off?” But Batuman has created an intellectual heroine, someone who strives first and foremost to understand and experience the world she’s been dropped into. This is why she’s so captivating — and why there is so much to learn from her.