In light of the Black Lives Matter Movement, which arose in response to the 2014 killing of Michael Brown and the persistent police brutality that plagues our nation, there is no better time to enlighten yourself about the Black experience. Beyond actively participating in the movement, actively being antiracist, actively donating to just causes and using your voice to fight for change, it’s important to immerse yourself in the literature that emerges from the Black community. Poetry about the Black experience has a way of sending salient messages that invoke change and is itself often a political statement. Black poetry is transformative, calling for and eliciting social change. Black poetry is a powerful tool — for challenging power structures, for mobilizing communities and for re-imagining a just and equitable future.

I chose to look at Claudia Rankine’s “Citizen,” Terrance Hayes’ “American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins” and Tracy Smith’s “Wade in the Water”; all three of these contemporary Black poets offer pertinent insights into the Black experience that invoke emotion and call for social change, for mobilization, for an equitable future.

1. Claudia Rankine “Citizen: An American Lyric”

Rankine’s “Citizen” breaks traditional poetic norms, stretching the conventions of American lyric poetry by interweaving a multitude of textual and medial forms into one unified work that portrays the overt racism that pervades the United States. Throughout the collection, she intersperses striking images from a variety of mediums — paintings, drawings, sculptures, collage and digital forms. To supplement her own message that Black bodies are often invisible, she uses these images to spin this reality on its axis, calling for the visibility of Black bodies and the Black experience.

In Rankine’s first and fourth chapters, she details the cumulative microaggressions that Black people face, such as racial profiling, the derogatory words aimed at Black bodies, and Black inaudibility and invisibility. Her second chapter follows the YouTube character Hennessy Youngman coupled with the racial incidents throughout Serena Williams’ life. This second chapter is all about anger and tensions boiling over. Youngman, in his one video, wryly suggests that Black people’s anger is “marketable,” which itself underlies the difficulty of Black artists to metabolize real rage; this is paralleled with Williams’ justified “outbursts” in response to the overt racial profiling of her Black, female body via targeted, unjust calls and suspensions.

Rankine acknowledges historic and present-day overtly racist acts. Rankine’s view of history centers around the way in which it marks the present; as much as history is burdensome and racked with pain, it can’t be forgotten because it is embedded in us. Therefore, history is itself a macroaggression that adds to the heaviness that builds up in Black bodies. Rankine writes in response to the shootings of Trayvon Martin and James Craig Anderson, the injustice in the Jena Six case, the 2011 English riots in the wake of Mark Duggan’s death, stop-and-frisk practices and Zinedine Zidane’s headbutt of Marco Materazzi in the 2006 FIFA World Cup, to name a few. She is acknowledging the transcendence and continuation of racist acts that target Black lives.

Finally, throughout “Citizen,” Rankins talks about release. Often, we hold all of our boiling-over emotions inside until we feel like exploding. Rankine, however, encourages a methodical release to avoid exploding and boiling over from all of the accumulating abuse. She says, “Feel good. Feel better. Move forward. Let it go. Come on. Come on. Come on” (66). This incantation really embodies how Rankine perceives the healing process — a constant cyclical practice of getting knocked down, picking yourself up, and moving forward (no matter how hard it might be).

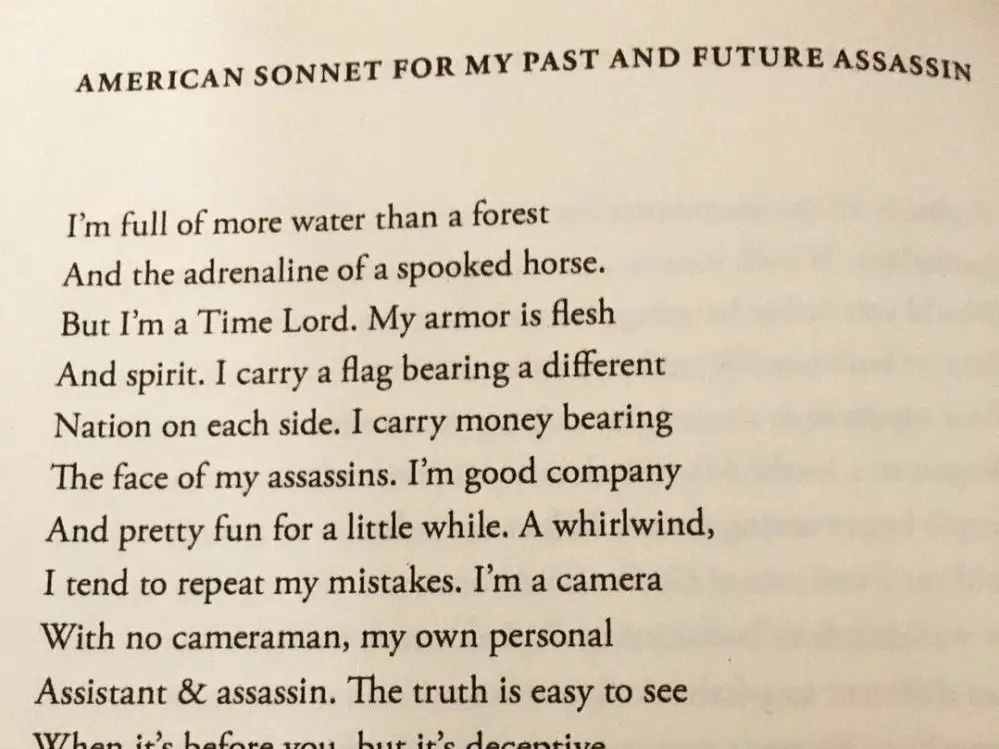

2. Terrance Hayes “American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins”

Hayes’ “American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins” explores the meanings of America and its erroneous history, through the address of his past and future assassins and love in the traditional sonnet form. Hayes wrote these sonnets during the first 200 days of Trump’s presidency, which is a deeply political statement in itself that showcases how integral politics and history truly are, especially for Black lives.

Throughout his collection, Hayes also explores how transcendental our dark history is, and notes how we carry it with us. Hayes primarily forms a connection with this history through the term “assassin,” which like the title suggests, embodies all of Hayes’ past and future assassins. Thus, the word “assassin” mirrors both a dark history and an unstable future.

Hayes’ use of the sonnet format, traditionally seen in love poems, was no accident; he wanted to retain a form of love for his assassins, despite their malicious attempts. With this sliver of love, Hayes reconciles with this dark history, rising against his murderers and oppressors by maintaining love in the light of darkness.

Anger, without a doubt, is also laced throughout this collection. Hayes begins to get increasingly fed up with his assassins as the collection progresses. His assassin is a murderer, a murderer of Black Lives (as exemplified by the listing of notorious states where Black individuals — Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Laquan McDonald and hundreds more were murdered for the color of their skin). Hayes’ interweaving of love and hate showcases the way in which our emotions are often tangled up with each other. Ultimately, with these small acts of love and a lack of fear for all his assassins, Hayes rises above, surmounting his oppressors.

3. Tracy Smith “Wade in the Water”

Smith’s “Wade in the Water” uses erasure poems, a format in which the entirety of the poem is composed of words from a source text. This structure allows Smith to honor historical Black voices that didn’t have a chance to speak for themselves due to the constrictions of the time. This leads to the emergence of deeply poignant commentary on the violence that Black Americans faced historically. Smith uses the Declaration of Independence, letters between slaveowners Mary and Charles Colock Jones and enslaved mother and daughter Patience and Phoebe.

Throughout this collection of Black poetry, Smith also makes a multitude of references to pop culture, making these poems accessible. She talks about David Bowie, the refugee crisis, the protest in Baton Rouge (and the powerful image of Ieshia Evans holding her hands out to be handcuffed, while her dress flows out behind her, seemingly levitating like an angel). This juxtaposition of historical erasure poems mixed with current events is powerful and shows how crucial it is to listen to this country’s long-buried Black voices. We need to learn from our history, so that we are not doomed to repeat it.

Similar to Hayes, Smith interweaves America’s racist history and present with an unlikely emotion. Instead of Hayes’ love, though, Smith champions Black joy. As she notes in an interview, she thinks about joy as something that we have to actively seek, something that we have to make space for, welcome. She also notes that it is harder and bigger than happiness. It’s a gift, but also a kind of choice. Ultimately, Smith compares joy to something that we work to grow; like a sapling, joy takes nourishment, water and light.

After this brief exploration of the themes that are embedded into these poetry collections, I hope that you will be inspired to pick up a copy of at least one, but hopefully all three. The future of our world depends on its inhabitants. A way to change the world is to first understand others’ experiences. One can only begin to understand the Black experience, historically and contemporarily, but immersing oneself in Black art and Black poetry is a step in the right direction, a step toward understanding, cherishing and uplifting Black poets that are often under-appreciated and unacknowledged. These three poetry collections are must-reads for poetry lovers and non-poetry lovers alike. Rankine, Hayes and Smith will render you a changed person and will galvanize you to enact change, fighting for a just and equitable future.