Normally, the road is quiet on a summer morning. Cars slink up and down the rural asphalt locked within two lines of old, stone buildings — the only spectators to the soft rumble of tires as the stagnant air sizzles under the rising sun. However, today the air is different in Dublin, an affluent suburb of Columbus, Ohio. Over the red brick sidewalks beneath the shortening shadows of slate, crowds of white people in red, blue and black face masks raise cardboard signs into the turquoise sky. “I CAN’T BREATHE.” “NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE!” The image of a black man, caught in a fatal chokehold under the knee of a police officer, unites them in fury and resolve. Drivers honk in solidarity.

Even in the most suburban parts of America, citizens swarm to advance the Movement for Black Lives. Not only has the initiative against systemic racism spread domestically, but Black Lives Matter is now an international phenomenon. BLM posters — either on social media or held within the grasp of an activist — are never far from sight, and never without poignancy. For countless people, the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and others have sown the seeds of rebellion, taking thousands to citywide protests of police brutality.

As the people stand up against injustice, it becomes imperative to understand the dual nationhood of America: the white and the black; the free and the asphyxiated. Although there exists no dearth of African American literature, some might be more accessible to the burgeoning civil rights advocate than others.

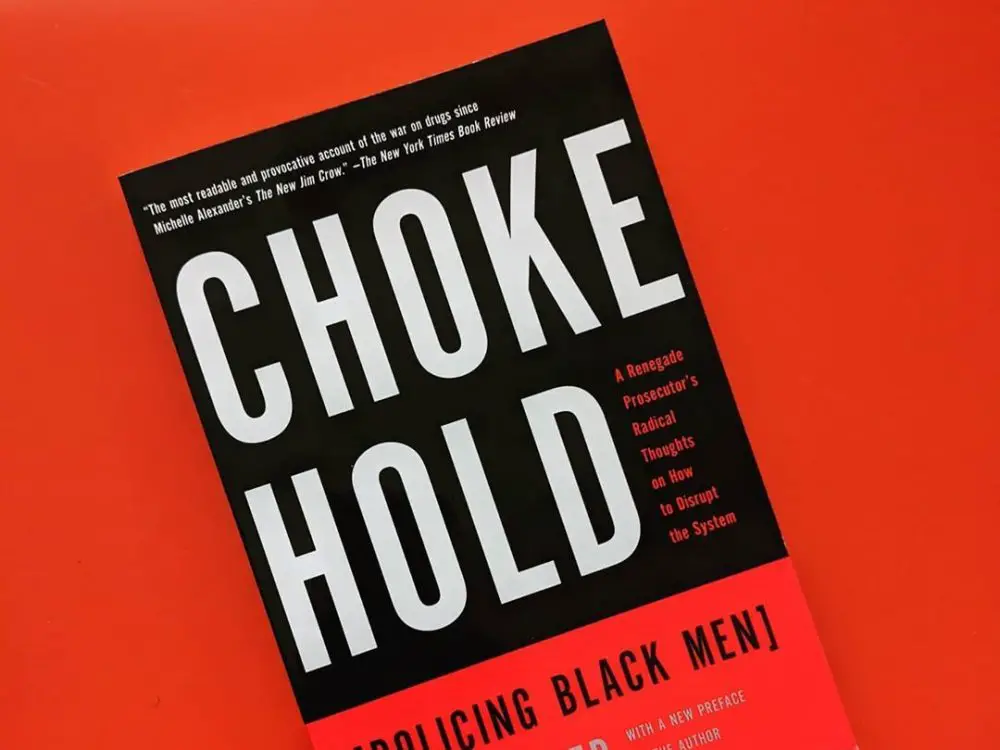

One great book to start with is “Chokehold: Policing Black Men,” written by Paul Butler and published just three years ago. The titular maneuver is both a literal and metaphorical term for black oppression, from racial bias to mass incarceration. Butler, a former prosecutor and professor at Georgetown University, is one of many advocates against corruption in the criminal justice system. Yet the breadth of information in “Chokehold,” from analyses of Supreme Court decisions to descriptions of fatal encounters with police, makes it especially ideal for those who want to get involved but don’t know what needs reforming in the first place.

To achieve the broad perspective necessary to tackle an issue as enormous as racist law enforcement, Butler draws from a number of authors, politicians and scholars to provide further reading after completing his book. From professors Robert Sampson and William Julius Wilson to Barack Obama, the work sprawls academia and politics with a deft consideration for those who have entered the conversation long before and alongside himself.

One of the oft-referenced writers is Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of the 2015 National Book Award winner “Between the World and Me.” In addition to quoting the author’s preeminent work, Butler shrewdly directs his reader to an article published by Coates in the June 2014 issue of “The Atlantic.” The piece, titled “The Case for Reparations,” argues that centuries of systemic racism, from slavery to segregation and redlining by the Federal Housing Administration, should prompt monetary compensation for black Americans. By making these references amid his own analyses, Butler establishes for his audience a major player in the fight against systemic racism.

“Chokehold” is also inspired by the work of Michelle Alexander, specifically her 2010 book “The New Jim Crow,” which puts mass incarceration on the same infamous pedestal as slavery and de jure segregation. Butler, however, rewrites Alexander in a slightly more contemporary context, bringing in new figures and examples, from Tamir Rice to Eric Garner, while yielding to her unquestionable influence on race politics in America.

Additionally, Butler incorporates intersectional analysis, a process coined by law professor Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw over three decades ago, into his own argument about the experiences of black men and women. Not only does this mesh well with his academic sensibilities, but it is also integral to a more comprehensive and personal reflection on Black America.

In the United States, there exists the presumption, in public as well as in court, that black men are criminals. Butler acknowledges this and many other insidious snap-judgments while peeling back what it means to be black, male, and American. The burden of this intersectionality amounts to a list of prohibited activities prescribed to black men that include: laughing in a group, driving a new car, arguing, wearing a hoodie, being in a white neighborhood and running.

Although none are illegal, each public activity gives the police an excuse to investigate, which, according to Butler, could lead to an arrest. The list is one piece of the author’s greater project to put the reader in a chokehold usually reserved for black men, as well as educate others on how to protect themselves. To a white person, the potential for any of these activities to result in a scuffle with the fuzz is almost unfathomable. While the enforcement of respectability politics is distressing, to provide this guideline for the reader is to humanize a demographic often alienated by white society.

Unsurprisingly, the author is a member of this minority, and his membership provides an insightful perspective on racial bias in the U.S. Butler once served as a federal prosecutor for years before becoming a professor at Georgetown and was later arrested in the 1990s on an unfounded assault charge. As police lied and witnesses failed to come forward, the lawyer-turned-jailbird discovered corruption he forgot as a prosecutor. That view from both sides of criminal justice provides veracity to his condemnation of systemic racism, especially for those who have no prior knowledge of what it means to be arrested as a black man.

It is the combination of ugly truths, the acknowledgment of a new canon of black political literature and the author’s self-placement within this literature that makes Butler’s work so accessible for mainstream audiences. Whether you’re marching in the streets, signing petitions or donating to charities, to know race-based discrimination, if you haven’t lived it, is to be a better advocate or ally. Of course, one needs to read more than one book to understand everything wrong with the criminal justice system; even the greatest writer couldn’t explain it all in one volume. Nevertheless, for those still unsure about the Movement, “Chokehold” might just spark a flame within.