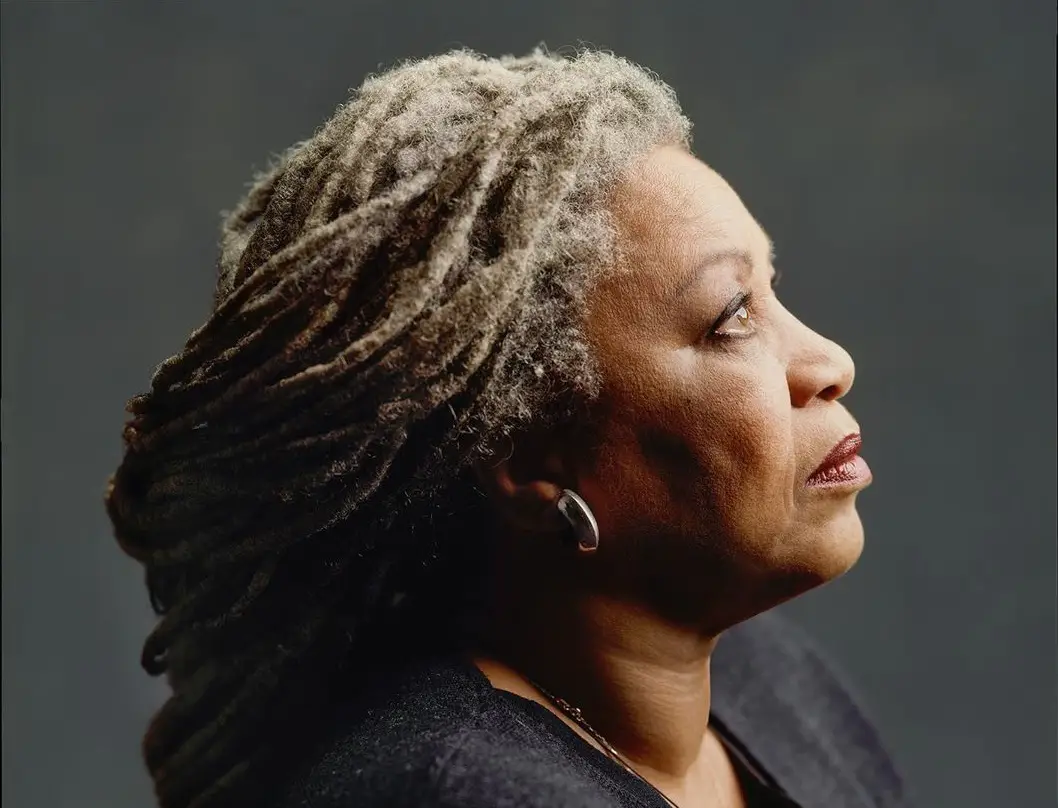

As avid readers know, it can be difficult to explore the works of a prolific author. If they penned five, 10 or even 20 books, where should an unfamiliar bibliophile begin? Toni Morrison, a Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, recently passed away, leaving behind nearly thirty works of fiction, nonfiction and children’s literature. Morrison, as a “towering novelist of the black experience,” forever changed the American canon. So how can a beginner dive into her abundant portfolio and rich legacy?

First, it’s good to get some background information; it typically provides insight into an author’s influences. As it turns out, “Toni” was not her given name. She was born Chloe Anthony Woffard on February 18, 1931, to George and Ramah Wofford in Lorain, Ohio. The new parents adored sharing African American stories and music with their children, which perhaps lended itself to the rhythmic quality of Morrison’s later writings.

In addition to her family’s stories, Morrison devoured the works of Jane Austen and Leo Tolstoy, both of whose work focused on the experiences of those overlooked. Soon, the budding author realized that she wanted to display another disregarded corner of reality: the experiences of black women, in all their complexity and heartache.

During her school days, Morrison’s memorable nickname surfaced. Classmates dubbed her “Toni,” since they could not pronounce her real name and, as you probably know, the moniker stuck. Morrison later attended Howard College and graduated with an English degree. After earning her master’s from Cornell University, she began a successful teaching career.

However, before reaching icon status, Morrison experienced difficulties that were formative to her career. In 1958, she married Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architectural student at Howard College. After giving birth to two healthy boys, Morrison found her marriage in tatters and, soon, she began life anew as a single, working mother.

At this point, the busy woman took a step back from her hectic schedule. Morrison honed in on her chief goals in life by asking herself a simple question: “What is it I have to do that’s so important that I’ll die if I don’t do it?” Immediately, Morrison knew she had to love her children well, and write.

“Oppressive language does more than represent violence. It is violence.” – #ToniMorrison

— Wilson Cruz (@wcruz73) August 14, 2019

In her books, attentive readers will notice ever-present musings on femininity and love. More specifically, Morrison chronicles the lives of black women who wrestle with these slippery concepts. In order to grasp the spirit of her writings, readers must track these themes. In three particular novels, the ideas unfold in a heroic, heartbreaking and deeply human way.

“The Bluest Eye” follows Pecola Breedlove, a young black girl living in the wake of the Great Depression. The 11-year-old suffers daily torrents of abuse, and gets told she’s ugly from every corner. In their insults, cruel people target her dark skin and eyes. As a result, the vulnerable girl longs for blue eyes, believing her bleak life will transform if she looks like Shirley Temple.

In the novel, Morrison contemplates beauty standards and the consequences of racism; uninclusive standards are damaging those who do not conform. Traditionally, women endure the most criticism for failing to meet beauty ideals, and for black women, the difficulties only intensify. In “The Bluest Eye,” Morrison shows that if society only allots love to Shirley Temples, the Pecola Breedloves of the world suffer.

“Sula,” published shortly after “The Bluest Eye,” explores a complex relationship between two disparate young women. Nel lives in a rigid, mainstream home with strict, conventional ideals. In her world, women marry early in life and become devout homemakers. Sula, on the other hand, experiences the complete opposite: She lives in a home run by her mother and grandmother, who outsiders see as odd and whorish. When the girls collide, their respective realities expand.

In “Sula,” Morrison illustrates the limited options for women throughout the 20th century. The surrounding world dubs women as either “homemakers” or “whores,” leaving no other personas available. Nel and Sula each emulate their mothers and grow to function within these constrictive labels. However, their love for each other transcends petty societal categories and, against all odds, the two girls build a meaningful friendship. Although complicated, their childhood relationship withstands the test of time (and various other trials).

Speaking of trials, “Beloved” describes the hardships encountered by a slave on the run. Morrison based the book on Margaret Garner, a woman who killed her daughter to spare her from a life of slavery. Garner tried to kill herself, as well, but slave catchers prevented her from carrying out the deed. In “Beloved,” Morrison follows a woman named Sethe, who committed a similar atrocity. The novel begins years after its primary conflict, when a familiar ghost begins to haunt Sethe’s house.

At its core, “Beloved” displays the psychological effects of slavery. Without freedom, Sethe’s motherly love becomes a desperate force of nature. Her maternal drive is chilling, gritty and difficult for readers to understand. As Margaret Atwood, bestselling author of “The Handmaid’s Tale” once said, “In three words or less, it’s a hair-raiser.” Although petrifying, “Beloved” prompts valuable questions about motherhood, liberty and the past’s crippling influence.

Toni Morrison was a national treasure, as good a storyteller, as captivating, in person as she was on the page. Her writing was a beautiful, meaningful challenge to our conscience and our moral imagination. What a gift to breathe the same air as her, if only for a while. pic.twitter.com/JG7Jgu4p9t

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) August 6, 2019

Questions are the most valuable resources a book can give. Without Morrison, some readers might never have contemplated the complex ideas she introduces. Pecola’s longing for blue eyes would seem like an irrelevant scruple, and not a heart-wrenching social problem. We might never examine female friendship or feel its unconditional warmth. In many minds, motherly love would remain a simple, fluffy sentiment.

If you think questions are precious, Morrison’s works will shimmer like a treasure trove of inquiry. If you tend to flee from unsettling ideas, then brace yourself for a long run. But if you abandon your idea of comfort, you’ll find a small miracle within each of her books. Pecola, Sula and Sethe will meet you in your sadness. These women’s stories will give you insight, edification and even an occasional laugh. At this point, Morrison’s abundant portfolio will no longer seem like a challenge. You’ll see her prolific career for what it is: a priceless gift.