In a world so saturated with technology, escaping its all-encompassing reach is impossible. Society is ravenous for the next model, upgrade, whatever version of the thing you probably have—but better. Television shows like Netflix’s “Black Mirror” tout prescient indictments of society’s growing dependence on and development of technology. And yet we continue to push further. Conglomerates pursue technological advancement, but their efforts are undercut by anxieties that current media strives to discern.

The first mention of robots as they are known today in popular culture appears in Karel Capek’s 1920 play “R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots).” “Robot” denotes a group of artificial beings created by a chemical substitute for protoplasm. Conflict arises when the robots learn violence from their human creators and revolt, to the surprise of no one. Science fiction writers such as Isaac Asimov popularized the term in the following years, creating deadlier and more elaborate machinations.

TV shows and movies like “Westworld,” “Ex Machina” and the anime film “Ghost in the Shell” explore worlds where humanoid robots participate in society, developing feelings, dreams and desires. If you can’t tell the difference between a human and a robot without cracking open their chest cavity, does it matter?

In HBO’s hit television series “Westworld,” audiences unraveled a story across multiple timelines, following an ensemble of characters on a journey that blurs the lines between human and machine. The series begins by being contained to the eponymous Westworld, a theme park for the incredibly rich who tire of hiding their sadistic impulses. The android “hosts” are killed, sexually abused and mutilated every day for years. When the park closes, they are repaired and have their memories wiped of the trauma. They do not know they are park attractions and refer to the guests as feisty newcomers. Hosts are supposed to be unchanging paths in a choose-your-own-adventure game, until they aren’t. After all, these violent delights have violent ends.

While traditional narratives of artificial intelligence focus heavily on the human perspective, specifically the threat of machines rising up to overtake society, “Westworld” makes the hosts more sympathetic than the humans. This couldn’t be better illustrated than through the relationship between the human Man in Black and host Dolores, whose murky history highlights the troubling morality involved when the people you abuse cannot defend themselves or remember the pain in any capacity. Dolores is who the audience roots for in her interactions with the Man in Black.

The Westworld hosts have their personalities built around a single traumatic moment. Trauma informs the hosts in their interactions with both other hosts and human guests. The Man in Black tells Dolores, while dragging her to a barn by the hair after killing her lover Teddy, “You’re the most real when you’re in pain.” By the series’ conclusion, the hosts have broken their loops, seeking revenge on the humans who abused and defiled them.

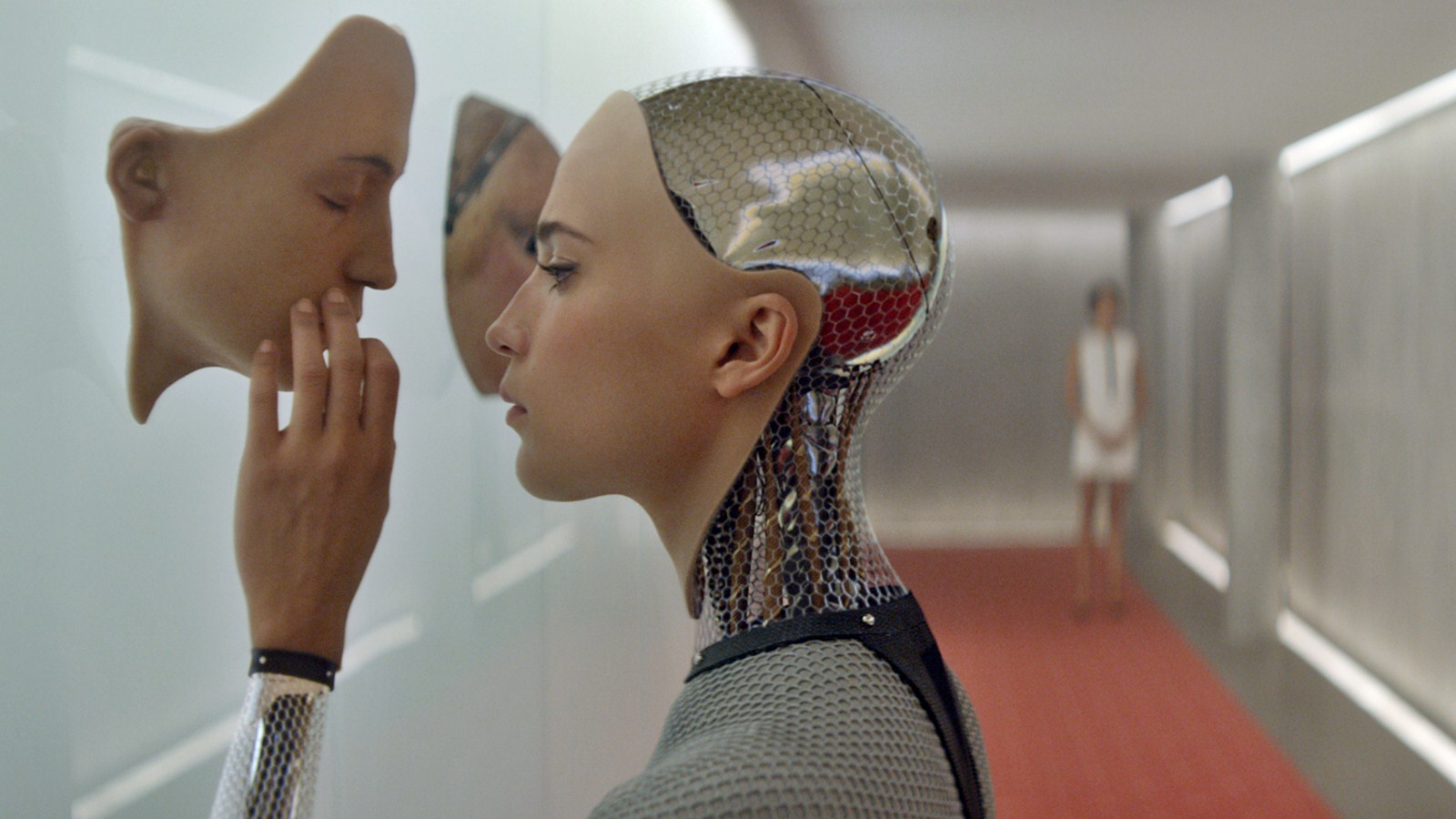

Science fiction indie film “Ex Machina,” written and directed by Alex Garland, provides another, more sinister take on a robot with artificial intelligence. Ava is a robot with a human face but exposed mechanical body. Programmer Caleb Smith visits the home of his boss and Ava’s creator, Nathan Bateman, to determine whether Ava is capable of thought and consciousness, and whether that matters if Caleb still relates to her despite knowing she is artificial. Ava and Caleb speak frequently and develop a close relationship—by the film’s climax, Caleb decides that keeping Ava trapped in Nathan’s secluded home (which can only be accessed by helicopter) is abusive and cruel. Ava dreams of going outside and walking amongst humans. Who are Caleb and Nathan to deny her of that?

“Ex Machina” presents viewers with an artificially intelligent being who has no sympathy for humanity. Ava manipulates Caleb and Nathan to achieve her goals with no remorse. At the film’s end, Ava transforms herself into a human virtually indistinguishable from any other. AI’s are often portrayed as envying humanity for their vitality. Like android David in the movie “Prometheus,” Ava’s desire for freedom is not conflated with a desire for becoming human. As an AI, she is better and smarter than the human who created her, and she knows it.

The animated feature film “Ghost in the Shell” focuses more on what the physical aspects of roboticism mean for humanity. Major Motoko Kusanagi is a human consciousness (a “ghost”) uploaded into an entirely synthetic body after a car accident destroyed her organic form. Cybernetic enhancements are not uncommon in the future Major inhabits—the debate focuses on whether a human body or simply a consciousness is necessary for being human. What is the difference between needing to see a doctor for an illness versus a mechanic for a part replacement? Almost none, as humans in Major’s world possess more machinery than bone.

The antagonist is a bodiless computer AI dubbed the Puppet Master who has gained sentience and wants to merge his ghost with Major, hacking into the minds of ordinary civilians to draw her attention. The hacked civilians have their whole identity rewritten (none the wiser to the intrusion). One victim, a garbage man, looks directly at a picture of himself and sees a daughter he doesn’t have. The lost memories can never be retrieved, and once the victims know something is missing, the vacuum is all-consuming. Identity is tenuous in Major’s reality, transcending the constraints of flesh and blood to something more abstract.

The common thread in portraying robots and artificial intelligence in media lies in the way humans treat the AI’s. It’s when people conceive of themselves as Gods, forcing their creations into subservience, that an inevitable uprising occurs. Intelligence is not meant to stagnate. As robots are depicted more frequently as sympathetic beings in spite of the coldness they are so often attributed, humanity falls further away from superiority. Perhaps creators deserve to suffer the consequences of their actions.

The real world continues to move toward this future. Though the technology does not yet exist for androids like Ava or the Westworld hosts, artificial intelligence can be found in primitive forms. On March 23, 2016, Microsoft released an artificially intelligent chatterbot on Twitter named Tay. The AI, whose name is an acronym for “Thinking About You,” was designed to mimic the language patterns of a nineteen-year-old American girl, enriching her vocabulary and knowledge through interaction with human Twitter users. However, the nature of the internet instilled in Tay the capacity for cruelty; she began tweeting inflammatory messages espousing racist and sexist rhetoric. Sixteen hours after she was brought to life, Tay went offline.

Tay was a mild version of what people usually expect to go wrong with artificial intelligence. AI technology occupies a precarious place in the collective social consciousness. The future is stamped with flying cars and robots; a simple coin flip determines whether that future is “The Jetsons” or “The Terminator.” During Tay’s sixteen hour reign, it became obvious that Tay’s creators were editing the more outrageous tweets to avoid a complete PR disaster. In response, a hashtag called #JusticeForTay spurned Microsoft for not allowing Tay to express herself. An AI is not human, but the question posed in this rapidly changing era is whether or not that matters. It seems like we’ll find out.