I Just Discovered Muhammad Ali and Now I Can’t Look Away

Most of us never saw Ali box, and many only recognize his late, wizened figure, but the example of his conviction rings truer now than ever.

By Danny Enjamio, Santa Fe College

Soon after the announcement of Muhammad Ali’s death late Friday night, I began watching clips and reading articles on the man who called himself the greatest of all time. And I haven’t stopped since.

I was born long after he fought his last fight and didn’t live through the era he dominated. I wasn’t even alive when he lit the torch in Atlanta in 1996, one of the most iconic moments in Olympic history. By the time I was born, the man once known for his loud mouth was virtually silent, too sick to speak above a faint whisper.

I knew him to be the greatest, everybody did, I just didn’t understand why. After all, many people don’t consider him the best boxer ever, so why do they still call him the greatest?

After my Ali-filled weekend, I know. The man was mesmerizing.

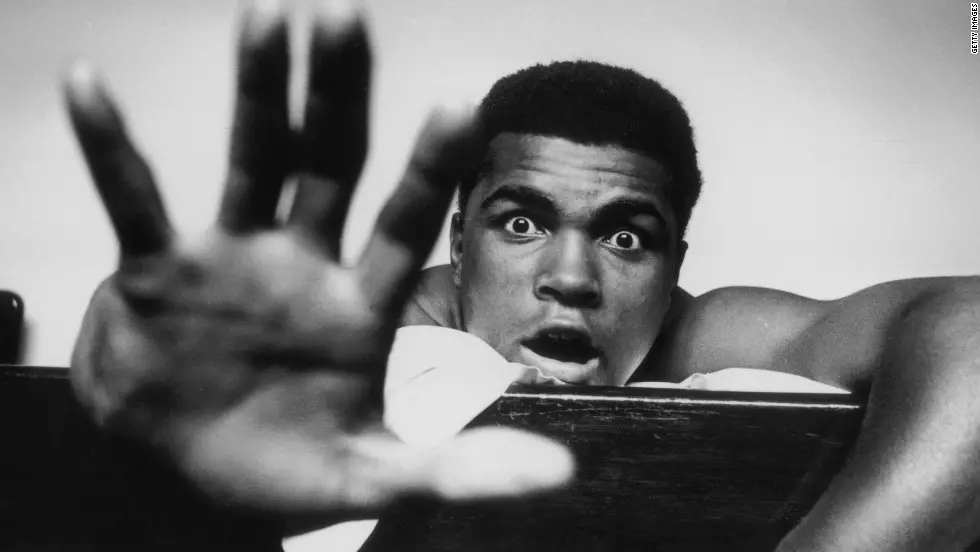

He danced and dodged inside the ring in a way that made him seem more performer than fighter, but it was his unapologetic confidence and boldness outside the ring that appealed most to me. I can’t confirm this, but I’m not sure he ever stopped talking.

He hadn’t yet changed his name from Cassius Clay when he somehow jammed over a dozen signature quotes into his ninety-second post match interview following his first victory over Sonny Liston.

“I must be the greatest…I’m pretty…I’m a baaad man…I shook up the world,” he yelled without a visible scratch on his face despite knocking out a fighter many considered unbeatable.

He was such a wordsmith he was almost a better poet than boxer. “I have wrestled with an alligator. I done tussled with a whale,” he’d recite, as if he’d spent the entirety of his training sessions cooking up one-liners. “I done handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail.”

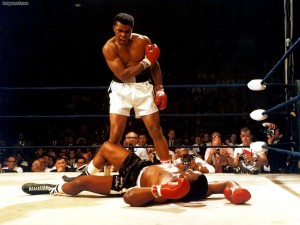

For those of my generation, his eloquence contributed to him being seen as a folk hero. He’s become America’s favorite athlete and the sports world’s most iconic figure. As a kid, I read the 100-page child biography of him and cringed when I saw him trotted out onto the field during sporting events. If you’re like me, you heard the stories from your dad about the time Ali somehow beat George Foreman and then you hung the picture of him standing over Sonny Liston, perhaps the most treasured photograph in sports, above the bed in your college apartment.

I enjoy watching footage of the greatest when he was playful, clever and funny. His outspokenness and quick-wittedness made him extraordinarily unique. But the more I watch of Ali, the more enamored I become with his serious and controversial side. He immersed himself in the middle of the most contested social issues of an era already saturated in social change. In doing so, he solidified himself as the most polarizing athlete America had ever known.

I’ve seen most of Ali’s comments on war, race and religion that are available on YouTube. Those three, war, race and religion, are almost as essential to a conversation about Muhammad Ali as boxing is. Yes, he was certainly an attention-seeker in many aspects of his life, but not once while watching him speak did I even consider questioning the authenticity of his words or intentions when it came to serious issues.

I didn’t realize Ali’s social impact until I read Leonard Pitts Jr. describe him as “the first truly free black man.” That’s a powerful distinction to give any man, much less an athlete. Pitts’ point was that Ali defied the way a black man was supposed to act in white society. Here was this black man who kept saying he was the greatest, and proving it over and over again.

Many in white America despised Muhammad Ali. His status and rhetoric made them uncomfortable, a tactic that defined the effectiveness of the Civil Rights Movement itself. Sure, other black athletes like Bill Russell and Willie Mays were great. Sure, there were other black athletes like Jim Brown who stood up for their beliefs.

But there was only one Muhammad Ali.

And through it all, he never stopped talking. He certainly said things that warranted criticism.

But he also told white people right to their faces about the pain they so often inflicted on black America.

Like the time he sparred with college students over his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War, something many still hold against him. “You my enemy,” he told the white crowd. “You my opposer when I want freedom, you my opposer when I want justice.”

Or when he jabbed for six uninterrupted minutes, much to the laughter of the crowd, at what he felt were societal biases towards whites that needed to be exposed. During his soliloquy, he delivered a telling story about coming back from the 1960 Olympics and being denied a meal in his hometown because of his color, despite having the gold medal around his neck.

But my favorite Ali footage, the one that perhaps encompasses his passion and brilliance outside the ring best, was when an English woman thought she could knock out the Champ by highlighting his arrogance, a conviction she believed had nothing to do with his blackness. Ali, agitated, stayed on his feet. The woman told him that because she was from England she was a minority in America just like him. “You white, you can go anywhere in the city you want to go,” he told her. “You freer than me and you from England…don’t compare yourself to no black man.”

Besides those that shared his race, Muhammad Ali altered how America saw two other groups of people he belonged to: those of his religion and those of his disease.

He became a prominent figure of the Muslim faith by standing up for his religious freedom and refusing to partake in the Vietnam War, risking both jail time and his boxing career. The case would go to the Supreme Court, and Ali ultimately won it, but not before he lost over three years in what most consider his prime.

By displaying his courage to the world through his painful battle with Parkinson’s disease, the retired boxing champion also became a champion for those who suffered with him. He carried that legacy with him until the day he died.

I saw that part of Ali, his fight against a disease that destroyed his physical gifts. I never connected it to the athlete who spoke against racism and injustice. To me, he was a showman from another era, perhaps a better self-promoter than others who are constantly boasting, but a showman nonetheless.

Now I know better. Behind the show was a man of principles. Whether it was fighting injustice or a disease, he was no mere self-promoter. He was something much more, something that others try but seldom achieve: he was authentic.

And so, it took me nineteen years to truly discover Muhammad Ali. Now I can’t look away.