The Joe Gould Standard

The “King of Bohemian New York” spoke seagull and wrote the world’s longest book, “The Oral History of Our Time.”

By John David White, University of Texas at Austin

Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” one or two of the Harry Potter books, and the freaking Bible—what you know about all of them, whether you’ve read them or not, is that they’re long as hell.

They’re too long, in fact—they’re the reason CliffsNotes exists. But for some reason, there’s a lot of people out there who still eat that stuff up. It’s in our nature to have a bit of a romantic fascination with books and movies that are mind-numbingly long. Writing an epic, any epic, is a pretty rad task because they are, after all, epics. As rapper Gibbs once said, “You ain’t gotta like my music, shit respect my hustle.”

Our respect for the hustle could be born of jealousy or curiosity or fandom, but usually it stems from an appreciation for the raw perseverance it must have taken for another human to actually sit there, ass to chair, and translate so many fleeting thoughts to paper.

Our respect for the hustle could be born of jealousy or curiosity or fandom, but usually it stems from an appreciation for the raw perseverance it must have taken for another human to actually sit there, ass to chair, and translate so many fleeting thoughts to paper.

The works mentioned all sit pretty comfortably under a million words, but the longest book in existence is estimated by many people to be around 7 million words. It’s “The Oral History of Our Time,”—it wasn’t a novel or a textbook or a memoir of a biographical piece, nor was it anything else, because the work was its own genre. The “Oral History” was a collection and recording of conversations the author heard and put on paper, which would come to represent a generation. In the author’s words,

“I could see the whole thing in my mind—long-winded conversations and short and snappy conversations, brilliant conversations and foolish conversations, curses, catch phrases, coarse remarks, snatches of quarrels, the mutterings of drunks and crazy people, the entreaties of beggars and bums, the propositions of prostitutes, the spiels of pitchmen and peddlers, the sermons of street preachers, shouts in the night, wild rumors, cries from the heart.”

In theory, it’s a pretty overwhelming idea—that we’re defined by our words to one another, not by the speculations of historians or political leaders looking back on what we’ve accomplished. In Gould’s opinion, to understand a certain point in history, simply listening to what’s being said around you has more bearing on reality than any academic perspective ever could.

Because the author knew that to understand someone you had to speak to them, Gould spent several decades writing anything and everything he heard. If he couldn’t listen, he would eavesdrop. As a result, his book had no plot or structure because it was just conversations on paper. All the writing was without sequence or pattern, and could hardly be understood by anybody but the author, if even him. Writers like Ezra Pound and E.E. Cummings regarded Gould as one of the most significant historians of the century, as well as a great friend and colleague.

And if you have ever heard anything about “The Oral History of Our Time,” then you probably know that it doesn’t actually exist.

I really wasn’t that surprised when I learned that a book of that length (which in written form was supposedly a stack of journals 7 feet tall, towering a foot and a half above the author’s own head) never existed—no publisher in their right mind would print such a monstrosity. I was actually relieved for reasons that I can’t explain.

But even stranger, the volumes upon volumes of this unpublished note-taking never existed either.

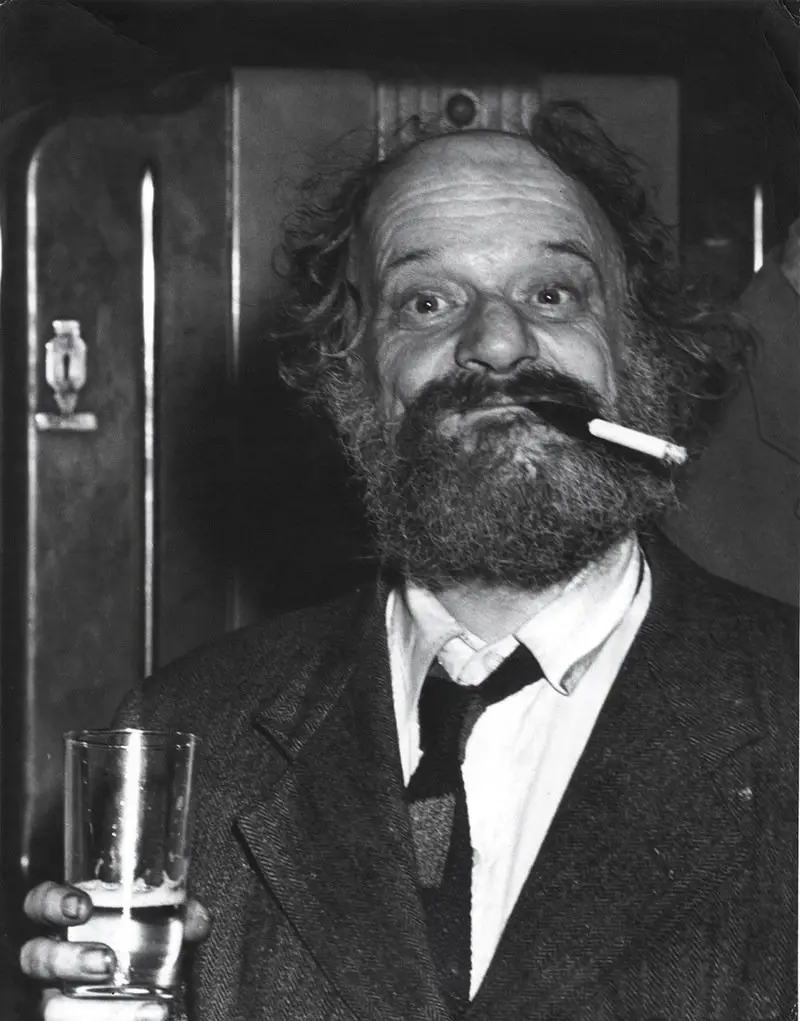

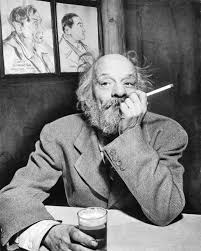

The life and works of Joe Gould, aka Professor Seagull, aka author of the longest book ever written, are all figments of the imagination of, you guessed it: Joe Gould.

While listening to an NPR interview with Jill Lepore, author of a book that documented a few unknown facts about the Joe Gould mystery called “Joe Gould’s Teeth,” I realized the unwavering obsession that other writers had for Joe Gould is much more profound than any actual detail about the real Joe Gould’s short life.

The title is a nod to Gould’s personality—he took little care of his possessions and lost literally everything all the time—he would lose his glasses, his money, his manuscripts when hungry publishers begged him for a taste of the lengthy masterpiece, but most famously he lost his teeth. It was a common practice for psychologists to treat mental illness with the removal teeth based on the presumption that a rotten tooth would also rot the mind.

Not only had so many great influential novelists, poets and intellectuals been fooled by his lies, but even years after his death and the revelation of his insanity, compulsive nature and utter lies of grandiose accomplishments, many journalists and writers continued to delve deeper into his myth, trying to understand the fascination with this crazy homeless guy.

Although Lepore recently resurrected Joe Gould’s story into current literature, he was the muse of many other famous journalists in the last century, most notably a writer for “The New Yorker,” Joseph Mitchell, who was regarded by his peers as one of the greatest reporter of his time.

Although Lepore recently resurrected Joe Gould’s story into current literature, he was the muse of many other famous journalists in the last century, most notably a writer for “The New Yorker,” Joseph Mitchell, who was regarded by his peers as one of the greatest reporter of his time.

To avoid writing the longest article in history, I’ll paraphrase some key points in Gould’s life that Mitchell reported on in the 60’s:

Joe Gould came from a rich family—strange, but rich. He talked to seagulls as a child—they whispered to him and he whispered back. He craned his neck and gawked and flapped his arms to tell the gulls stories in their native tongue. He brought this “skill” with him throughout his life—acting like a bird at bars and parties in a drunken stupor, which coined him the nickname Professor Seagull. Teachers, parents, friends couldn’t tell if he was a prodigy or if he should be locked up.

He failed the majority of his courses in Harvard and ultimately dropped out. He once walked five hundred miles to Canada to straighten out his life. He was homeless and compulsively wrote down his thoughts and his observations day and night, but that was later proven wrong. After Gould’s death, Mitchell revealed that all the notes Gould had been supposedly taking—and witnesses swear he was constantly, constantly writing—were just the same few irrelevant passages again and again.

Jill Lepore also mentions in her book that writers were drawn to Gould because of the fact that he was always writing—a skill they all wished they possessed. Since there was no complete works ever found by Gould, only a few dirty notebooks without context or fluidity, the scribblings of conversations he heard in passing seemed less like an anthology and more like the ravings of a lunatic.

In Gould’s heyday—when he could string together intelligent thoughts and maintain the façade of his fake book, he was the King of Bohemian New York. Unfortunately he eventually his hair and his teeth, and he hurt several people and a woman that was close to him.

When his mind really began to slip, it became more common to find Gould covered in fleas and sores. He scared off most of the reporters that were interested in him, and ironically, after Mitchell’s expose about Gould, he was unable to write another word for the rest of his career.

Lepore says that Gould’s fate was likely lobotomy and death in the largest insane asylum of the 1960’s.