Talking about sex, frankly and openly, is never thrilling. You first hear about it from your same-gender parent, who tells you of all the mysterious and wonderful changes your body will undergo as you go through puberty.

As you start to understand body odor, pubic hair, menstruation, ejaculation, acne and growth spurts, you may have asked: “Why?” Your parent may have answered you directly: sex. You reflect on that, jarred by their honesty, and develop and grow into your teenage years. This is all, of course, a best-case scenario.

In most cases, you hear about the pleasures and horrors of sex from your friends, in school or online. As you gain a vocabulary of sex, you start reading the world in a new way and everything is seen under a new, sex-conscious filter — especially music.

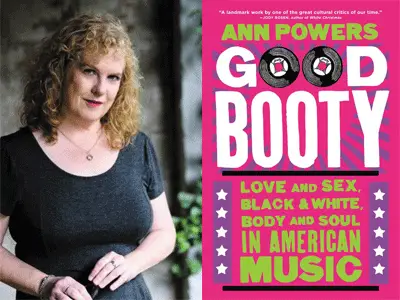

Ann Power’s new book, “Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music,” chronicles the inextricable historical links between sex and music which go overlooked. Powers’ central argument is that American music has an ability — perhaps a duty — to access and express erotic feelings, and as a nation we fully accept this definition. When we chat about sex, it’s discomforting or childish. When we sing about sex? That’s a different story.

Powers has a great deal of authority on the subject of American music as a long-standing popular music critic, but as a woman, she offers a new perspective in rock criticism, which can seem like a boy’s club. Since analyzing the entire body of American music is an insurmountable task, Powers hones in on key settings in the development of erotics in music: antebellum New Orleans, jazz-age New York City and post-World War I Memphis, to name a few. In each setting, Powers considers key performers, songs and events that contributed to the openness of expression that exists in music today.

Powers is sharpest when she writes on the relationship between crowd and performer, which she continues to build in every chapter. The introduction of “Good Booty” showcases how “the sex scenes of American music reveal the most intimate cruelties we have wrought upon each other, alongside the pleasures and kindnesses.” The inherent ambivalence of our own sexual attitudes and the ways these feelings take form in music are essential to building the link between each chapter.

As we choose how to react to our sexual selves, Powers argues, the voices and styles of pop music change. One of her best examples is when she delineates how Elvis’ distance, yet proximity to pure sexuality charged audiences: “the sizzle comes as much from the mastery of his self-suppression as it does from the revelations of his lasciviousness.”

While her prose can be rich, as shown from that excerpt, there are moments when it blanches. For instance, in the book’s first chapter, which compresses one hundred years, leaving the analysis spare and less colorful. There are other times when Powers attempts to synthesize biography with conventions of performance and new technologies that changed the way music is consumed. Her biographies are stellar and connect performer to performer, creating clear chains of influence that are easy to follow. Powers seems to be aware of her strengths, for tracking people and their contributions to American music takes up most of the book.

As a result, some other key features of music production are left out. Powers briefly mentions the invention of recording technology and the ribbon microphone, both of which had massive influences on the way audiences listen and respond to music. She also mentions how the vinyl record allowed the listening experience to become private as well as public, and only ties her point to the erotic charge of the performer.

The ribbon microphone, which captured voices more clearly than other technology, is tied to the same point. It is easy to imagine how new technologies fostered private sexual relationships between listeners and dissuaded attendance to public shows, both of which are relevant topics in music history to discuss.

However, Powers does mention the innovation of the internet and its effect on music in the final chapter, “Hungry Cyborgs: Britney, Beyoncé, and the Virtual Frontier.” Her evaluation of the social, cultural and technological factors on the production of Britney Spears’ music is so savvy. Powers writes that Spears’ “multiple identities—teenybopper queen and hard-core vixen, or, to put it in classic sexist terms, virgin and whore — lifted her beyond those categories, or even negate them,” in an online landscape “where regular folk could reimagine themselves as airbrushed superpeople.” Powers’ analysis of Britney is the rare intersection of biography and frequent bold social claims — it’s nearly poetry.

The book does, of course, try to thread a cohesive narrative of eroticism in music, which at times can feel shoehorned into the narrative at hand. Powers’ lens can be too narrow, dismissing genres of music in paragraphs, as she does with early country music. For example, while her claim that country music’s primary theme is the relationship between the wild and domestic sides of life is ostensibly true, some in-depth unpacking would lend merit to the claim. Some genres and artists may be less evocative and sexual than others (many of whom enjoyed popularity), but that doesn’t mean they should be excluded.

Paradoxically, “Good Booty” reads best when Powers focuses on specific artists and ignores others. Perhaps the cause may lie in the design of her study — to summarize over two hundred years of rapid cultural shifting without missing a beat is a massive task to undertake. Powers’ efforts to make historical factors digestible leads her to adhere to a typical narrative of white appropriation of black talent and tradition.

Her summary is accurate, sure, but in comparison to the rich, original explorations that fill the rest of the book, it seems unnecessary to remind her readers of the original sin — exploitation of black bodies. “Good Booty,” then, could work better as a collection of essays without the ham-handed links between chapter.