Lani Sarem’s YA fantasy novel “Handbook for Mortals” was released on August 15, 2017. A week later, the book was ranked number one on “The New York Times” Bestseller list, knocking down Angie Thomas’s critically acclaimed “The Hate U Give” to second place. That same day, amidst controversy that Sarem bought her number-one title, the book was removed from the list for not meeting proper inclusion criteria.

A novel selling well straight out of the gate is not an uncommon phenomenon. Books make the NYT Bestseller List all the time, some even faster than Sarem’s novel. John Green’s “The Fault in Our Stars” debuted at number one, selling thousands of copies before publication. So did Thomas’s.

The problem lays in the fact that Thomas’s novel dominated the NYT list since being released in February of this year. The next book to take the title would be seen coming a mile away, and would likely have generated more than enough buzz as it worked its way up the list. It would be no easy feat.

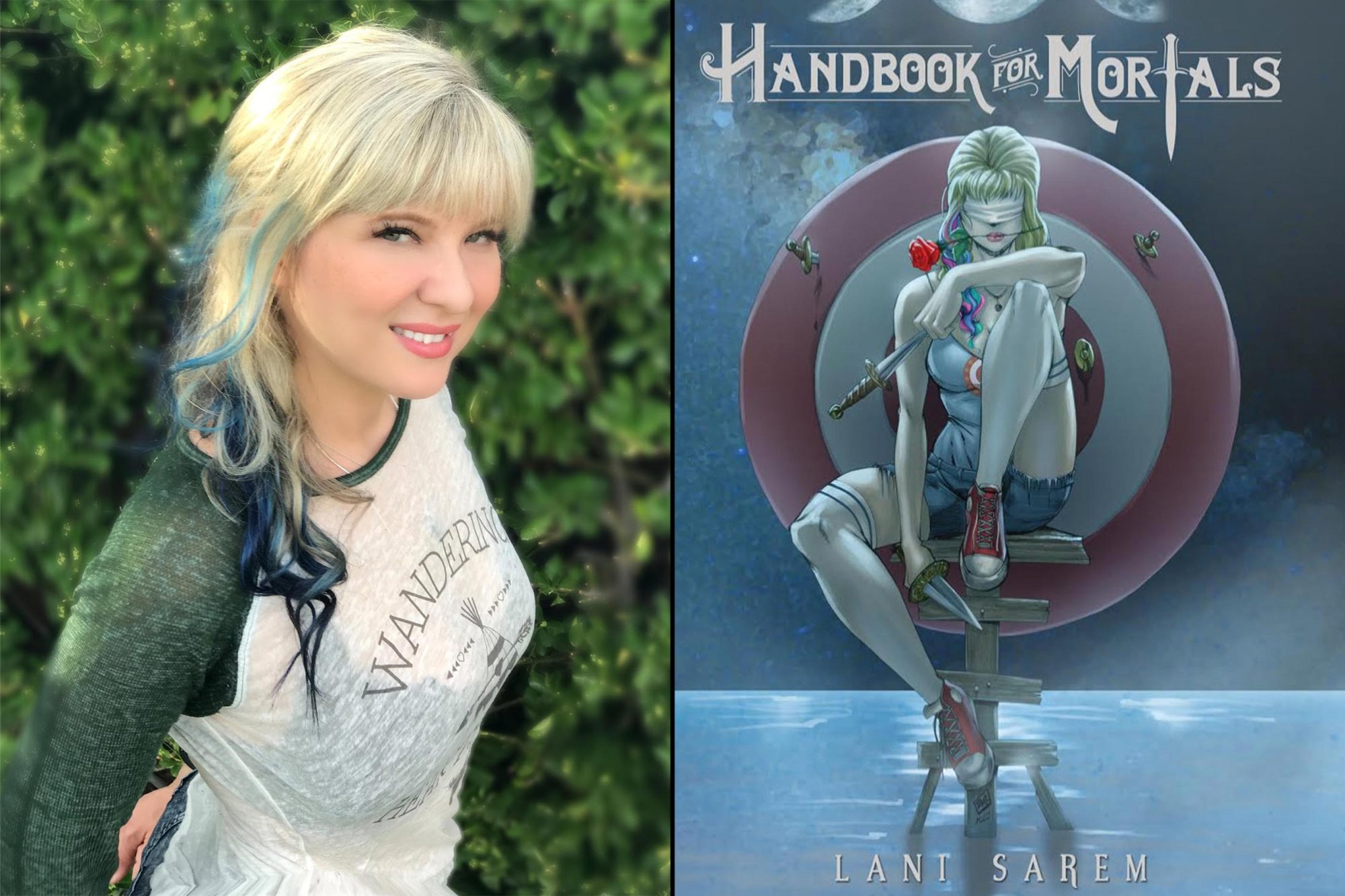

No one had heard of “Handbook for Mortals.” Prior to release, the novel boasted only five reviews, one from Sarem herself, on Goodreads. There were no tours scheduled, no circulation of Advanced Reader Copies (ARCs) around popular blogging platforms. Before fingers were pointed and accusations were thrown, only a few articles about the novel could be found on Google, all press releases published within two months of the publication date. The YA book community, known for being loud and proud about new favorites, was silent. Despite these circumstances, a movie adaptation with “American Pie” actor Thomas Ian Nichols tied to produce and starring Sarem in the lead role, was already in the works. The novel is Sarem’s first foray into publishing after a history of music managing and acting in small, uncredited roles.

“Handbook for Mortals” follows a young woman named Zade, the most recent addition to a dynasty of “magick” users, fortune tellers and tarot card readers. Eschewing the desires of her overprotective mother, Zade leaves her home in Tennessee to forge a new path in Las Vegas. With a bit of supernatural interference, Zade gets casted in a big and bright magic show on the strip, hosted by notorious and obviously named magician Charles Spellman. Eventually, there is a love triangle, a near-death experience and a race against the clock.

Excerpts of the novel are not very promising; Sarem spends more than one paragraph describing her protagonist’s hair and outfit (who bears an uncanny resemblance to the author). If an editor ever got their hands on Sarem’s novel pre-release, they did a terrible job. The publishing company behind “Handbook” is GeekNation, a pop culture media site with no other novels or publishing experience in their repertoire. Currently, a search for both Sarem and her novel respectively turn up nothing on the site.

YA author Phil Stamper became the first to notice the oddities surrounding Sarem’s rise to success. In a series of tweets, later confirmed by “The New York Times,” Stamper uncovered Sarem’s attempts to strategically buy up copies of her own novel to hit the list. This is not a new tactic; the authors of many conservative novels bulk-buy copies of their own book for the numbers and later resell them or give them away. It’s not illegal and not very hard to do. However, “The New York Times” has provisions for cases like these.

In order to get on the bestseller list, a book has to sell five-thousand copies in one week. The list does not count cumulative sales from the release date, just those in a single week. Though the newspaper considers the algorithm for choosing the weekly list to be a trade secret, the sale numbers are gathered from select retail locations to better reflect the desires of the consumer. An order of thirty books or more is considered to be a corporate purchase. A committee then reviews the novels chosen for the list for any discrepancies. For authors who bulk-buy their novels to boost their chances of cracking the top ten, an image of a dagger is placed next to their name, denoting a high number of corporate purchases. “Handbook for Mortals” bore no such image.

In his sleuthing, Stamper received messages from several book store employees providing evidence that anonymous buyers placed orders for just under 30 copies of “Handbook” at stores all over the country. Sometimes they went as high as 29 books, purchasing for events they claimed not to care if the books ever made it to them on time.

Stamper’s thread of tweets went viral, especially in the YA book community. The outrage garnered the attention of “The New York Times,” who released a statement that afternoon revealing a revised list, citing an “unusual pattern of purchases” as reason for Sarem’s removal. In the end, Angie Thomas returned to her rightful spot at the top, to the delight of many.

And what was Sarem’s response to the controversy? In an interview with “The Huffington Post,” Sarem accuses the YA community of gatekeeping: “I didn’t play by the normal YA rules. I didn’t […] send out galleys two years in advance, and I didn’t go talk to the people that thought I should come talk to them. I did it a different way. Do you only get to be successful in the YA world if you only do it the way that they think it’s supposed to be done?” In addition to this, she denies having any knowledge of attempts to scam the list, claiming some of the books were bought with the intention of reselling them at Wizard World cons.

The power of having “#1 NYT Bestseller” on the cover of your novel cannot be understated. I know that I, like many others, give books on the list more consideration than I would a random novel on a shelf. It’s possible that Sarem wanted that recognition before she unleashed her debut novel on the world as a major motion picture, though the likelihood of that happening seems nonexistent now. Maybe the world dodged a bullet.