There is no denying that the United States is a diverse country, and diversity can only serve to help the country grow. When thinking of impactful black inventors, minds might trail to the inventor of beauty products, Madam CJ Walker, the first self-made woman millionaire, or to the contributions of Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson who inspired the film “Hidden Figures.”

Yet, many other black inventors, unbeknownst to most, have played significant roles in improving the lives of the public. Here is the list of black inventors that have impacted the modern lifestyle.

Sarah Boone

Not much is known about the black inventor, Sarah Boone, who saved people from wrinkled clothes with her invention of the ironing board. Before Boone’s invention of the ironing board, many people resorted to using a board made of wood laid across a table or a set of chairs to iron their clothes.

Other ironing boards were patented before Boone’s, but none of them had the same level of sophisticated design that Boone’s had. Her board, an improvement to the ironing board, was made up of narrow wooden boards and had a reversible feature making it easier to iron each side of a sleeve.

With collapsible legs and a padded cover, the board was designed to be put away; her design became the predecessor for the modern version of the ironing board. After her patent application was approved in April 1892, Boone became one of the first black women to receive a patent.

Sadly, she was not recognized for her work and there is no record of whether her invention was produced and marketed.

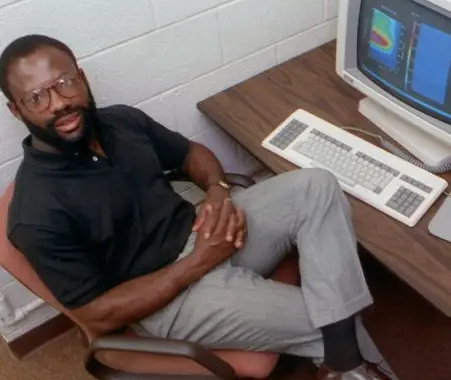

Philip Emeagwali

Nicknamed the “Bill Gates of Africa,” Philip Emeagwali was born in a poor family in Nigeria in 1954. Due to the fact that his father could no longer afford to continue paying for his school fees, he was forced to drop out of school at 14.

Instead, his father continued to teach him at home; Emeagwali would continue to perform daily mental exercises. Viewing intellect as a way to escape his harsh upbringing, Emeagwali studied hard and earned a scholarship to Oregon State University. There, he received his bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

Emeagwali saw the natural efficiency in the process of how bees build and work with honeycomb and concluded that if a computer could imitate this process, it would be much more powerful.

Emeagwali used 65,000 processors to invent the world’s fastest computer, which performs computations at 3.1 billion calculations per second, and is now used to forecast weather and predict the likelihood and effects of global warming. This discovery earned him the Golden Bell-Nobel Prize.

Marie Van Brittan Brown

Restricting the entrance of unwanted guests, the first home security system was invented by a black inventor, Marie Van Brittan Brown. Brown was born in Oct. 1922 in Queens, New York, where she continued to live in an unsafe part of the city until her death in 1999.

Growing up in this area of New York, even when the police were contacted, the usual response was slow. As she was working as a nurse, her husband worked with electronics, creating a work schedule that did not fit the typical nine to five. As a result, Brown invented her security system to help promote the safety of her and her family.

Brown’s original invention had three peepholes at various height levels, a camera with the ability to slide up and down allowing a person to see through each peephole, monitors and a two-way microphone.

Additionally, the device had an alarm button that, when pressed, contacted the police immediately. Brown and her husband filed the patent for her invention in August 1966, and their application was approved in Dec. 1966.

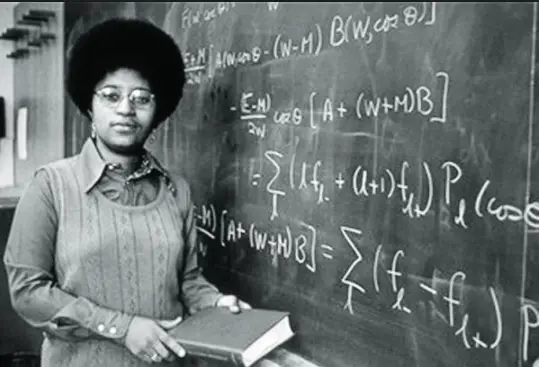

Shirley Ann Jackson

Shirley Ann Jackson, born in Washington D.C in 1946, accomplished many firsts for a black woman. Graduating as the valedictorian from her high school, Jackson was accepted into the MIT where, despite discouragement, she majored in physics.

Proving her naysayers wrong, she received her bachelor’s degree in 1968. Learning from the first black physics professor in her department, James Young, Jackson decided to stay at MIT for graduate school. In 1973, she received her doctorate degree, making her the first black woman to earn a Ph.D. in physics from MIT.

After leading successful experiments in theoretical physics, the knowledge gained from Jackson’s test runs were used to facilitate developments in telecommunication including the invention of the touch-tone telephone and the portable fax, and her research was also used as the backbone behind the technology for caller ID and call waiting.

Jackson was the first black person and woman to chair the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and additionally, she was the first black woman to be elected president and then chairman of the board of the American Association for the Advancement for Science (AAAS) and to president of a research university, Rensselaer University where she currently serves.

Garrett Morgan

Born in 1877 in Kentucky, the next black inventor on this list helped prevent future accidents from occurring. Although Garrett Morgan stopped attending school after the sixth grade, he was ambitious and had an impressive understanding of machinery.

While this might tempt many people into dropping out of school, Morgan learned everything he knew about machines after working in a textile factory.

Morgan soon after became the first black adjustor, fixing and improving machinery. He then opened his own repair shop in 1907 and launched a clothing business with his second wife Mary Anne Hassek.

Although it was a difficult period for black Americans, Morgan made enough money and became the first black man in Cleveland to own a car. After witnessing a serious accident, he invented the traffic signal in 1922.

Morgan eventually sold his invention to General Electric, and although it is now widely used, Morgan received $40,000. Although it might not seem like too much these days, $40,000 during that time would equal about $569,997.69 today.

From the invention, Morgan also made it a point of interest to support to the black community by joining the NAACP, donating to black colleges and starting “The Cleveland Call” for black Americans.

Patricia Bath

Born in 1942, Patricia Bath is an ophthalmologist and an inventive research scientist who advocates for blindness prevention, treatment and cure. Inspired to study medicine after hearing about Dr. Albert Schweitzer’s services to lepers in the Congo, Bath received her medical degree from the Howard University College of Medicine.

Simultaneously interning at Harlem Hospital and Columbia University, Bath observed that half of the patients at the Harlem Hospital were blind or visually impaired. Yet, strangely enough, the eye clinic at Columbia had few blind patients.

Following her observation, she conducted a retrospective epidemiological study which had shocking results. Her research found that the rate of blindness among black people was double of that in white people.

She concluded that the high rate of blindness among blacks was a result of the lack of access to ophthalmic care. As a result, she proposed a new discipline known as community ophthalmology.

Community ophthalmology promotes eye health through public health, community and clinical ophthalmology to underserved populations.

However, her contribution to ophthalmology didn’t stop there. After five years of research and testing, Bath invented the laserphaco probe which was a new device to remove cataracts, and in 1988, she became the first black female doctor to receive a patent for a medical invention.

Her other accomplishments include being the first woman to chair an ophthalmology residency program at Drew-UCLA.

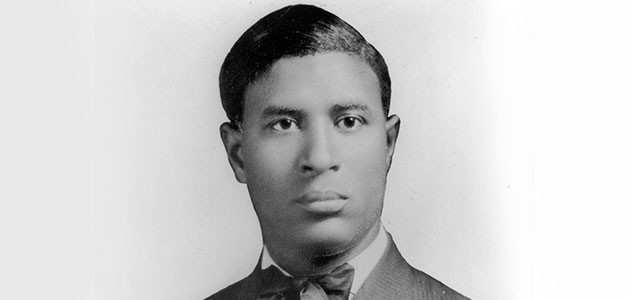

Charles Drew

As a black inventor, Charles Drew altered medicine by establishing the first blood bank and is the first black surgeon examiner of the American Board of Surgery. While attending Dunbar High School, Drew’s academic and athletic excellence earned him a scholarship to Amherst College in Massachusetts.

Years later, he was offered a research fellowship by the Rockefeller Foundation to study blood at the Presbyterian Medical Center. Critically during that time, he discovered plasma could be stored and preserved for future emergencies.

A little while after earning his Ph.D., Drew directed an experimental program focused on collecting, testing and distributing plasma in Great Britain. Ending the trial run on a successful note, Drew and his team collected blood from about 15,000 people and gave over 1,500 transfusions.

Drew was then appointed as the director of the first American Red Cross Plasma Bank. By recruiting 100,000 blood donors for the U.S. Army and Navy during World War II, his leadership helped save the lives of thousands of wounded soldiers.

Unfortunately, the U.S. military had a segregated blood system that refused to give blood from black people to white soldiers. Citing the fact that there is no evidence of differences in blood between the races, Drew criticized the policy and resigned from his position.