The Harm in Privatized Prisons

The Department of Justice announced it will no longer use private prisons, but what does that mean for our nation’s incarcerated?

By Lauren Grimaldi, Roosevelt University

Though the United States accounts for just 5 percent of the global population, it is responsible for 22 percent of its prisoners.

Regardless of where you stand on the issue of criminal justice reform, that statistic is problematic. Though the prison system, and by extension the issue of punishment itself, is ineradicable in modern society, it could certainly benefit from some changes.

While the Department of Justice still has a long way to go for full reform, their decision to end the use of private prisons is a step toward progress. For years, private prisons have existed, in theory, to help alleviate overcrowding at federally-run prisons. In the 1980s, a time in which the War on Drugs was in full force, the incarceration rate skyrocketed. The resultant overcrowding led the U.S. government to privatize some of its jails, forcing the state to turn to corporations to solve the problem of overpopulated prisons.

In 1984, the Corrections Corporation of America took over a facility in Tennessee, marking the beginning of what has been a very tricky issue in criminal justice. Though private prisons were formed in hopes of lowering costs for taxpayers, they did anything but. In fact, there are even some instances in which the cost of incarceration is higher in private prisons, raising the question of the economic viability of third-party penitentiaries.

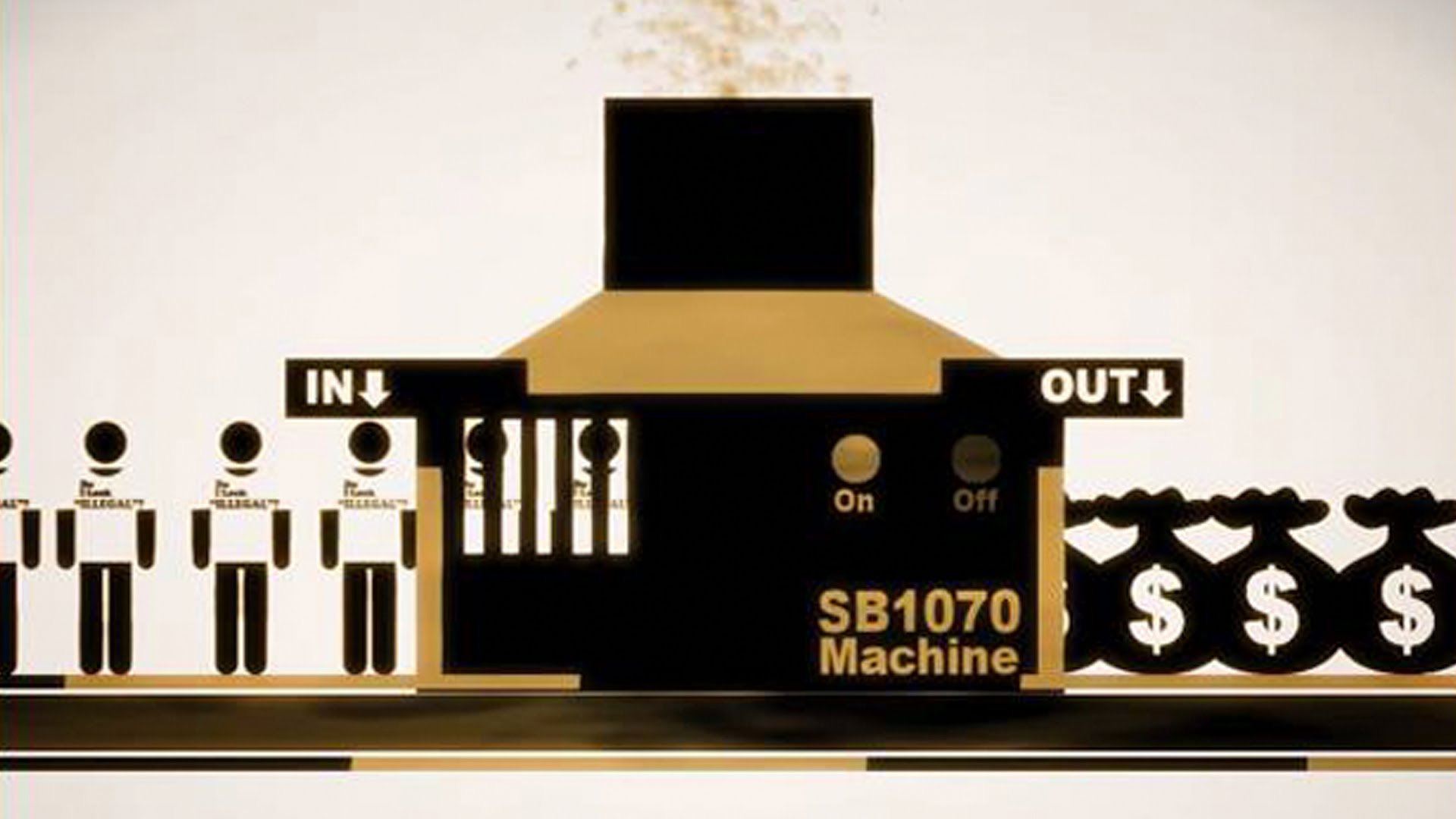

As a result, private institutions have turned into what is essentially a business: The more inmates the jails take in, the more money they make. Though no one wants to see the imprisonment rate go up, the business model of private prisons relies on it. As in any business, owners wish to make as much money as possible, but prisons cannot be treated in the same way.

Across the board, it was found that inmates at these independent institutions were also less safe than those in a federal facility. They are squeezed into their cells and often given inadequate resources. In addition, because resources at these prisons are scant, inmates receive no guidance on how to adjust to society once they are released from jail. This, in turn, only increases the rate of recidivism.

Throughout the election, criminal justice reform has been a popular topic. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s policy on private prisons is on her website as follows:

“Hillary believes we should move away from contracting out this core responsibility of the federal government to private corporations. We must not create private industry incentives that may contribute—or have the appearance of contributing—to over-incarceration. The campaign does not accept contributions from federally registered lobbyists or PACs for private prison companies and will donate any such direct contributions to charity.”

As for Donald Trump, there is no official statement on his website regarding criminal justice reform. However, he has shown support for private prisons, and his “tough on crime” initiative would do little to help the growing incarceration rate.

In fact, immigrants make up a large portion of the population in certain third-party correctional facilities. Trump’s policy on immigration is tough, and his stance on criminal justice will only hinder the system, not help it. While there remains no guarantee that Secretary Clinton will be able to implement all of her criminal justice reform policies, she will, at the very least, try to fix the problem.

When prisoners are seen as dollar signs, the focus shifts from helping inmates to reform their behavior, to profiting from their mistakes. Though those responsible for a crime deserve to be punished for their actions, the mass incarceration rate will only stagnate or increase if nothing is done.

The ending of federal private prisons is certainly a step toward meaningful change, but there are more ways to help end the problems that inmates face both in and out of jail.

One of the more pressing issues in ending mass incarceration is the recidivism rate.

In a study that began in 2005, it was found that more than 50 percent of released prisoners were arrested again within one year; after three years, rates of recidivism jump to 70 percent, and after five years, nearly three of every four prisoners have been reincarcerated.

In order to help prisoners readjust to society, it is imperative that they receive guidance while incarcerated, either through taking classes or meeting with counselors, amongst other options. While unfortunately an unsustainable practice for violent offenders, those arrested for petty theft and low-level drug offenses could certainly benefit from working with someone to reform their life.

Though it cannot eradicate crime, restorative justice, a method in which the perpetrator and the victim work together toward mutual recovery, is a more humane way to ensure that the criminal has an opportunity to reform.

Ultimately, the Department of Justice has made the right choice to end the use of private prisons. But, even this momentous decision will not end the high incarceration rate in the U.S.; lasting reform is worthwhile, but it will take time.