Why Socrates is Irrelevant

An influencer of ivory tower education and internet flame wars, Socratic skepticism can play an inflammatory role in the age of information.

By Shiloh McKinnon, Reed College

If you’re an American college student, you’ve probably heard of Socrates.

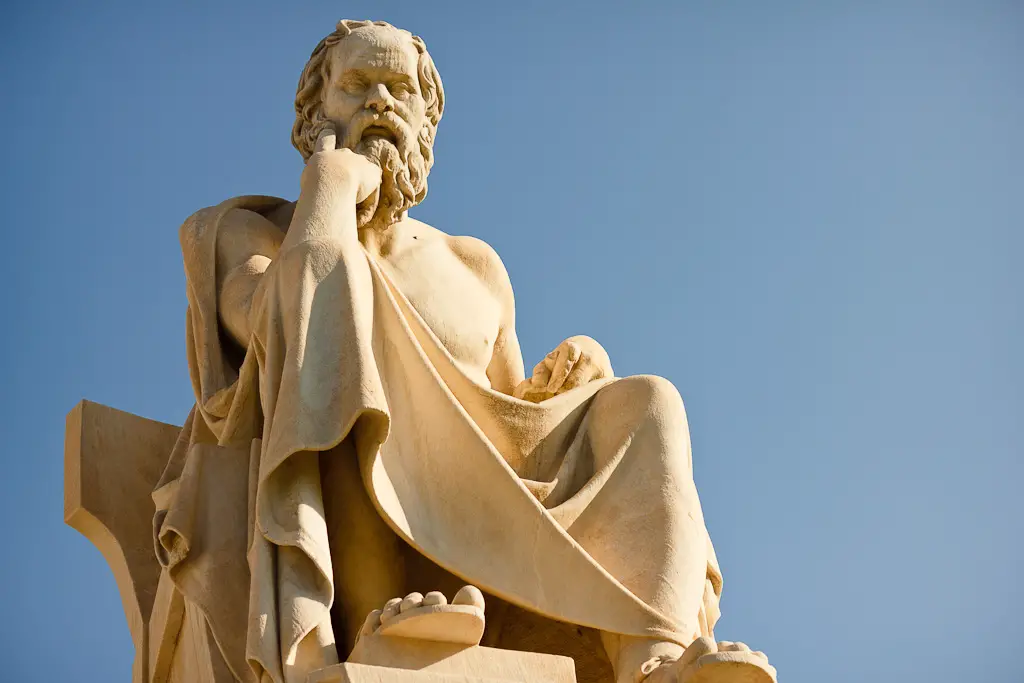

Like many other Ancient Greek guys, he’s hailed as the founder of his field, in his case, philosophy. A lofty title, for sure, but according to my teachers from middle school on, one he earned through his unique way of thinking about the world.

When I was first introduced to the term “the Socratic Method” in seventh and eighth grade, I thought it was the coolest thing ever. As a curious kid who literally never shut up (my most common comment in humanities was to make sure I left room for others to speak), the Socratic method was perfect for me.

As my teacher explained, the core of the method was that Socrates taught his students as if he were just another student. Teachers employing the method may ask questions to steer the conversation toward productive topics, but for the most part, it was left to the students to talk to each other and construct arguments and understanding about the text or issue at hand.

Of course, the Socratic Method made life hell for my less extroverted classmates, and I have a number of friends whose grades suffered because they couldn’t clinch the participation score. All in all though, I massively benefitted from Socrates’ influence in my life.

So what happened? How did I come to be so critical of the Father of Philosophy?

In middle school, it never occurred to me to question why we never learned anything about what Socrates actually said. He focused on making his students teach themselves, and that was that. Wasn’t it enough that he pioneered a method of schooling still relevant today?

I obviously didn’t answer this question then, given I didn’t even think to ask it until I’d found myself taking a year long class that focused on Ancient Athenian history, literature and yes, philosophy. Why did I question his importance? Well, in my second semester, I finally read the closest thing we have to a record of Socrates’ teachings, Plato’s “Trial of Socrates.”

In the first book, “Euthyphro,” Socrates asks his friend Euthyphro to give him a definition of piety, seeing as he is about to be tried for impiety and corruption of the youth. Euthyrphro gives Socrates the most relevant answer he can come up with, that piety is doing what is pleasing to the gods. Socrates rejects that answer with the argument that the gods disagree, which leads to an entire book worth of Euthyphro trying to clarify what he means as Socrates attacks one or another aspect of his definition. At the end of the book, Euthyphro is incredibly confused and Socrates still doesn’t have a definition of piety.

You can start to see how these techniques would evolve into what we see in 100-comment long Facebook threads today. When a number of my classmates and I got into an argument with alumni about the curriculum and the topic of trigger warnings, I noticed that a lot of the arguments being thrown around were more focused on discrediting the other side than trying to make a real point. I was really confused. We were all educated at the same school that praised Socrates as a great thinker and a cornerstone of modern academics, so why was a serious discussion about teachers’ rights and student needs being treated like a high school debate?

Probably because these alumni were arguing exactly like Socrates has taught them.

According to Plato’s accounts, Socrates wasn’t so much a philosopher as a debater. He wasn’t interested in proving himself right so long as he could prove his opponent wrong. When telling the jury about his experience seeking out a man wiser than he, he said, “It is likely that neither of us knows anything worthwhile, but he thinks he knows something when he does not, whereas when I do not know, neither do I think I know; so I am likely to be wiser than he to this small extent, that I do not think I know what I do not know.” Basically, he may not actually know anything, but at least he’s not a hypocrite about it.

I understand why someone with a graduate degree can make the argument, ‘I know more than you so I’m right,’ to argue with a college student on the internet; it’s getting a little away from Socrates’ actual message, but it’s definitely the way he demonstrates his knowledge.

One thing I’ll give Socrates: He was a great debater. Not quite good enough to argue his way out of being sentenced to death, but that’s probably because his style didn’t really allow for that sort of argument. Or for actually coming to any conclusions whatsoever.

In his day, that was important. Socrates taught people to question what their leaders told them, in Athenian society that went a long way. I’ll agree with Socrates on one front—authority figures can’t be trusted just on the basis that they have authority. And honestly, I really appreciate the Socratic Method, at least as a teaching tool. I just think it’s time to remember that since his preferred method of debate ended with him getting sentenced to death, maybe it’s not something we should be copying.