The victory of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil’s October presidential elections provoked an an uncanny mixture of both fear and joy among the citizens of Brazil. The policies that Bolsonaro has proposed are reminiscent of the actions of the Brazilian military during its two-decade long dictatorship. For anyone who has grown frustrated with the corruption of previous governments, Bolsonaro represents something of a return to order; those whose memories of Brazil’s dark past are still present, however, are terrified. Regardless, at the forefront of the opposition against the neo-fascist leader are the country’s university students, many of who are not afraid to continue carrying out a historic tradition of political resistance.

What disturbs young Brazilians the most is Bolsonaro’s political past. Brazil’s newest president-elect was an active participant during Brazil military dictatorship of the Cold War. A former paratrooper in the military, Bolsonaro’s chauvinistic policy ideas threaten the safety of women, immigrants, Afro-Brazilians, LGBTQ people and even the Amazon. In past instances, he has even stated that he is in favor of dictatorship and is an admirer of Chile’s own military dictatorship, which lasted from 1973 to 1988, ultimately leading to thousands of deaths. In one speech, Bolsonaro has promised to his supporters to recognize labor unions as terrorists and to commence a “cleansing never before seen in Brazilian history” — a bold statement, considering Brazil’s history.

Bolsonaro’s rhetoric and political vision are nearly identical to those that Brazil’s military junta enacted from 1964 until 1985. Both the previous dictatorship and Bolsonaro’s plan threaten the autonomy of universities. Similar to the military occupations of universities in the 1960s, the police in Brazil have already begun raiding universities for any pro-democracy, anti-fascist materials. All anti-fascist-learning material or art were deemed “illegal,” until Brazil’s Supreme Court deemed such operations to be a violation of freedom of speech. Moreover, rightwing lawmakers called for students to denounce any and all professors whose political ideology did not align with theirs. Freedom of thought among both professors and university students are under a threat that is all too familiar. The hostility and intimidation making its way in university campuses are naturally an inevitable reminder of Brazil’s darker past.

To Brazilians, Bolsonaro’s far-right politics are essentially remnants of the military dictatorship that their country endured during the Cold War. From 1964 to 1985, military generals, rather than civilian politicians, ruled the South American country through systematic torture and massacres. During the dictatorship, the Brazilian police, armed with military training provided by the U.S., waged war on its own citizens, significantly university students, whom they accused of trying to subvert the government.

On campuses, torturers and military squads targeted students for transgressions as minor as complaining about cafeteria food to protesting the coldblooded assassination of a classmate. Rhetorically, the Brazilian military was able to justify its crimes against humanity by alleging it committed such acts in the name of defending the country from becoming “another Cuba” — that is, succumbing to communist rule.

In any country, high school and university students consistently play a key role in opposing violent governments. Because of their sheer numbers and the vast resources that they have at their reach, university students can form wide networks between different universities. Even within the United States’ democracy, students have sometimes found themselves organizing their own unions and student governments to foment a sense of community. In Latin America, however, students find that when dealing with unresponsive governments, forming formal federations is vital in order to demand the government to acknowledge basic human rights.

In Latin American military dictatorships, both paramilitary violence and state repression serve to silence the voices that make up a nation’s civil society, such as its trade unions and journalists. Any form of organization among groups of people would raise suspicions, and often lead to brutal deaths or “disappearances.” Nevertheless, resistance efforts among Latin Americans usually emerged in what was left of civil society. In Brazil, despite the threat of torture and murder from police, student movements from the 1960s to the 1980s organized public demonstrations to counter the state terror that was gradually making its way into their own college campuses.

Perhaps the most influential group in Brazil’s history is the National Student Union (UNE). The UNE was a common target of the military during the dictatorship. The president of the UNE in 1964 even had to seek refuge in a foreign embassy, and thousands of others were forced into hiding, according to historian Victoria Langland. Yet, by 1968, the outlawed student union began to forge enough power to challenge the dictatorship’s legitimacy. The Brazilian youth collectively understood that their lives were at risk in these activities, but they embraced the threat of death as an inevitable part of their urgent fight for human rights.

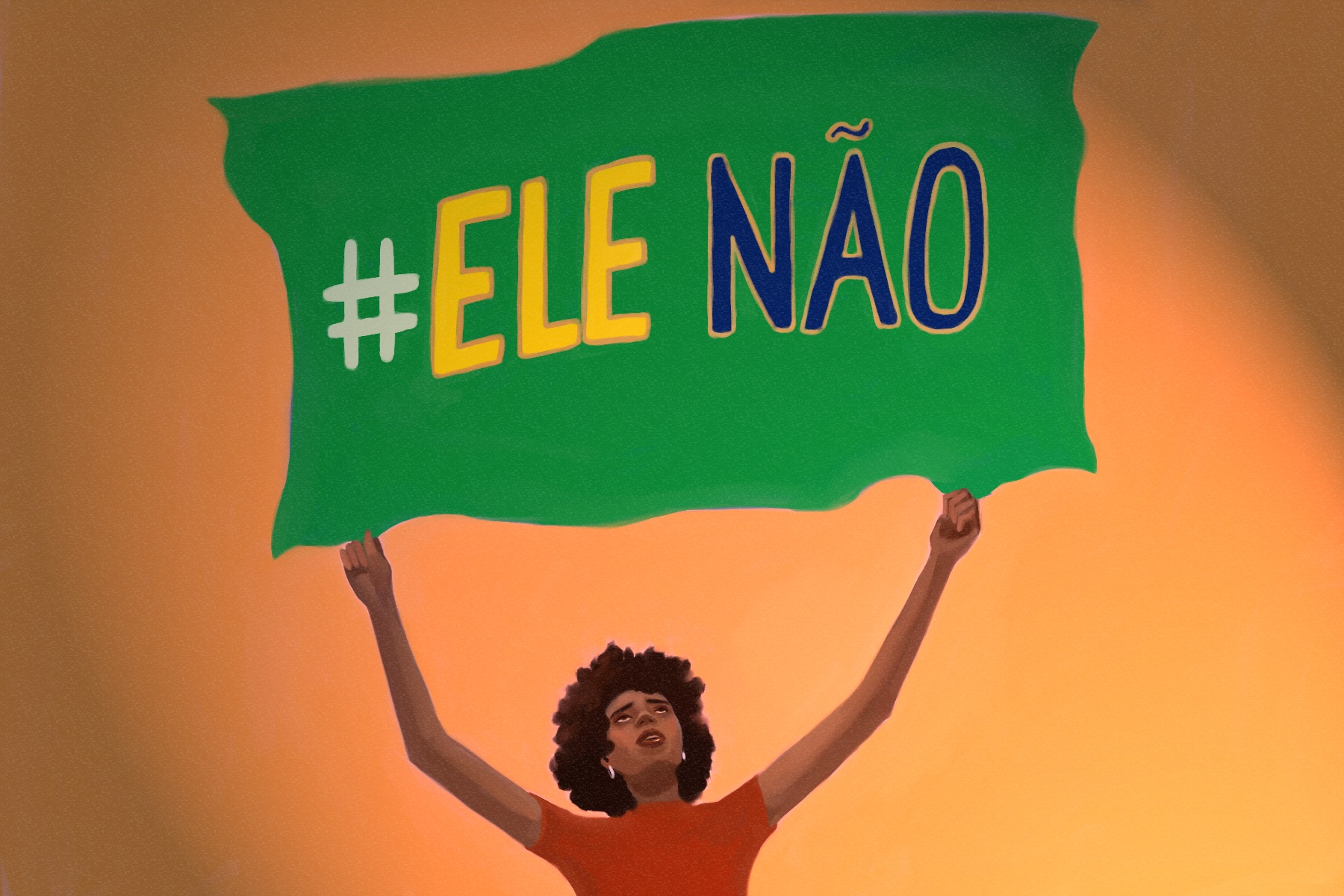

Much like during the Cold War, contemporary student movements in Brazil represent a key source of opposition against Bolsonaro’s fascist politics. Students at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro State placed antifascist banners on campus several days before the presidential election. When asked to remove them by Rio de Janeiro’s electoral court, they did so, but later displayed the banners to the public again in defiance. In 2018, the historic UNE of Brazil has already initiated the early processes of mobilizing youth to respond to Bolsonaro’s electoral victory. Not only are they organizing within their own campuses, but they’ve formed networks between various parts of the country, forming a united front.

Most notably, on Oct. 30, 30,000 university students in São Paulo organized a demonstration in rejection of Bolsonaro. Despite the students’ nonviolence, the military police detained six protestors and claimed the detainees were carrying Molotov cocktails and vandalizing banks. The protestors have all denied these allegations. The counterinsurgency police, on the other hand, unleashed tear gas and bombs on the groups, while dressed in full riot gear. Much like in the dictatorship of the 1960s, the military and police see civil society, a necessary hallmark of democracy, as a portion of society that they need silence. Nevertheless, these Brazil’s student movements will most likely continue to harness grassroots power even after Bolsonaro formally takes the office of president of Brazil.

Under Bolsonaro’s new reign, university students skipping class to march while dressed anti-fascist shirts and carrying wrinkled political banners will continue to represent a threat to the Brazilian government. Still, with the past serving as an example and with their own peers constructing nationwide solidarity, Brazil’s university students have the potential to amplify their voice loud enough to transcend the government’s politics of hate.