Fighting Sexual Violence with Education

The program might have some problems, but it was still the only test I’ve ever been eager to take.

By Kara Mercer, Northern Illinois University

It’s amazing how much an activity loses its appeal when you’re required to do it, like when a teacher assigns a book you might otherwise enjoy had you picked it up on your own.

That’s why when I read the word “requires” in an email from my university, I worried that students might gloss over its contents.

“The new state law, Preventing Sexual Violence in Higher Education Act…requires that all students attending Illinois public universities be provided with ‘sexual violence prevention and awareness programming’ multiple times throughout the academic year.”

Though no one likes a test, least of all students, at least the one my university was requiring would be useful. The email, which was sent to every student on campus, also expressed a hope that the awareness education could help prevent sexual misconduct on campus. My second thought, after initially worrying that the wording might cause my fellow Huskies to lose interest, was that quite frankly, I’m pretty sure the testing wouldn’t be enough.

The program is called “Title IX Education and Awareness,” and consists of a series of thirty-one slides on Blackboard, a course managing system some universities utilize. Each slide features an explanation of what the Title IX is, including the types of sexual misconduct prohibited under the law.

Originally passed in 1972 to prohibit sex-based discrimination in any federally-funded education program, Title IX means schools are required to address all sexual misconduct on campus in order to protect students, as well as victims (and abusers) of sexual crime. Not only is violence covered, but so is stalking, domestic abuse, sexual harassment and gender- or sex-based discrimination, all of which were discussed in the training.

The slides include explanations and videos from faculty reading off a prompt in the background. At the end of the presentation, there is a ten-question test that students must pass with an 80 percent to show comprehension.

Overall, the presentation and test take very little time; I completed it in a break between classes. The slides were easy to read and were written in clear, plain language, in order to make their message less confusing for students. Videos on the slides broke up the text, explained certain topics and provided examples for different scenarios. The programming even included the “Tea Consent” video, a clip that illustrates how ridiculous it is to not understand what consent is, since one of the educational objectives of the awareness program is to learn the importance of saying yes.

The module was not without problems, however, as for one, it becomes unavailable after the deadline to complete the training in March. The presentation includes useful information, and should be available to students past the deadline.

Second, students can also just blow through the test without committing anything to memory. There is nothing to stop students, such as a time limit or slide-to-slide quiz, from advancing to the next page, so students uninterested in the module could simply click through the presentation, and, since the test questions are multiple choice, they can just guess on the test.

Also, once the test is complete, there is no going back to see what answers were wrong, which means that the test-takers never learn what they got wrong, which somewhat defeats the point of the education.

Despite some flaws though, the Title IX awareness presentation is a great way to educate faculty, staff and students on the laws and procedures for investigating sexual misconduct cases. Sexual assault is a prominent problem in higher education, so more schools should take the time to set up online applications, hold seminars or teach students how to deal with sexual misconduct on campus, whether as a victim or witness.

Helpfully, the awareness education went through some bystander procedures, and listed the contact information for the various resources on- and off-campus to receive help. More states should pass legislation such as Illinois’ Preventing Sexual Violence in Higher Education Act, which requires multiple annual tests and education on sexual misconduct laws; it also requires that the training makes explicit the meaning of consent, how to contact survivor services and what the strategies are for bystander intervention, which should be information easily available to students on any campus.

With all of the uncertainty concerning the stance of the secretary of education nominee, Betsy DeVos, on sexual misconduct in higher education, it is especially important for colleges to step up and provide the necessary education for students. In 2011, the U.S Department of Education issued a letter and official guidance on how schools must deal with sexual misconduct cases. When asked if she would uphold those guidelines, DeVos did not answer directly; then, when pushed, offered that it would be too “premature” to give a direct yes or a no.

Under the Obama administration, preventing campus sexual assault was a staple in the education department, but, unfortunately, there is a disturbing amount of uncertainty regarding how seriously Trump’s cabinet will address sexual assault on campus.

Even though I hope my fellow students took the Title IX training seriously, I think it will be insufficient.

Even if schools aren’t required to provide any kind of awareness training, students should take the initiative.

Students, faculty and staff should take bystander classes to learn how to help their friends, peers, students or themselves. Universities should make it clear on their websites, or through student portals, what the process is for reporting sexual misconduct, and then take those reports seriously to protect their students.

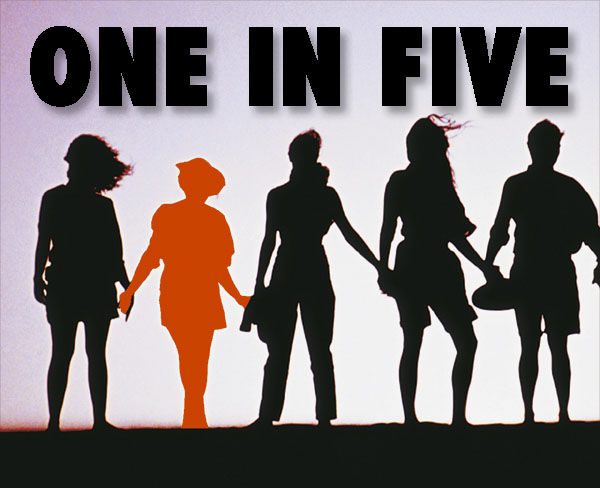

Sexual assault on campus is an epidemic, afflicting nearly 20 percent of college women. It is heartening to see steps being taken by my university system, though those steps should be only the beginning. As a president takes office who may care very little for the problems of college females, it is once again up to the students, faculty and staff of universities to take the initiative. If the federal government refuses to take the problem seriously, we must.