Literature has always been something of a contested territory, the question of to whom it belongs — or should belong — fertile ground for a centuries-long debate. Is literature a product of an elite intellectualism that seeks to exclude the common man from entering the upper echelons of educated society, which, for most of history, has been taken to mean the West? Or is it a space that everyone has access to in some form or another, whether it manifests itself through song, drama or oral storytelling aspects of cultures across the globe?

Embedded within this debate, too, is the debate over what constitutes literature. Should genre fiction such as sci-fi, romance, mystery, young adult and fantasy be categorized as “literature”? Or is literary fiction — the kind of fiction widely considered to be the mark of an “intelligent” reader — the only type that can be reasonable accorded to the title? And then there is, of course, the more glaring issue: what does this debate even matter in a rapidly globalizing, technologically advancing world where the written word appears to be in some danger?

Enter the Nobel Prize in Literature, caught in the eye of the literary storm, battered as much by politics and nation as it is a commitment to maintaining the highest literary standards. To some, the prize is crucial to fostering a healthy, global literary culture; to others, it is a Jurassic invention that has always been more inclined to rewarding obscure European authors or writers who are embroiled in some sort of political controversy at the expense of controversy-less writers working outside the Euro-American sphere.

And to those who aren’t invested in the literary world at all, the prize might very well mean nothing at all. Despite what you think of the award, I do believe that, in many ways, the question of whether Nobel Prize in Literature is relevant or not is asking whether literature, in all its variations and permutations, is relevant or not.

When Swedish inventor and philanthropist Alfred Nobel envisioned the five categories that make up the core of his eponymous prize, the person chosen for literature, according to Nobel, should be one “who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction.”

Nobel, in essence, was asking for individuals who would pioneer new modes of literary expression, just as he was asking for vanguards of chemistry, physics, medicine and peace — change and adaptability, then, are founding principles of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Even though it honored writers working from realist traditions (the predominating literary movement leading into the early 20th century) for the first quarter of its existence, the Nobel committee seemed determined to select those who were innovating the genre, honoring writers such as the Norwegian Knut Hamsun, who started experimenting with the stream-of-consciousness literary technique that would strongly influence novelists and poets alike for the next 50 years, and Rabindranath Tagore, a Bengali poet responsible for bringing Eastern literary traditions to the West.

It was also the prize’s good fortune (or incredibly awful fortune, depending on how you look at it) that it was established right at the turn of the century, when the world itself was changing and adapting at rates beyond what anyone knew, faster than anyone could have ever imagined. Nothing was spared in the whorl of industrialization, colonization, militarization, and expansion of trade routes — not economics, not politics, and most certainly not literature, which, in the 1920s, was undergoing a revolutionary metamorphosis: the move from realism to modernism.

Modernist writers and artists threw realism to the wind, favoring instead abstraction and experimentation. To them, anything that would break down recognized systems of meaning and representation was welcome. Writers pushed the envelope in ways people wouldn’t have thought possible. Literary titans such as Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Ernest Hemingway penned their seminal works during this period from 1920 to around 1940.

The Nobel Prize, still committed to adaptability, rode the new wave; awarding modernists semi-consistently through to the sixties, showing that, when it came to the facts and form of art, the prize committee was open to new ideas. Even when one moves past the modernist period to the postmodern era — when writers crucial to the development of literature on a global scale such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Wole Soyinka were finally afforded a stage — one sees that the Nobel Prize had its finger on the world’s literary pulse.

So, what happened? What crisis of faith compelled the Committee for the Nobel Prize in Literature to choose Bob Dylan, a songwriter whose credentials as a writer of literature are a matter of discussion? And what brought them back to form with the selection of Japanese-British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro?

Bob Dylan’s recognition, in my opinion, was the clearest indication that the Nobel Prize in Literature was begging to be noticed again. With a few notable exceptions, many of the writers chosen for the award were highly obscure. Most were Eastern-European figures (a chronic problem for the committee) whom no one outside Europe knew or particularly cared for. Surely Bob Dylan, loaded with international appeal, would vault the award to its former status as the standard-bearer for all literature.

Whether or not they upheld literature, it certainly was a calculated move towards a millennial cool. Now, I don’t believe Bob Dylan deserved his Nobel Prize in Literature — his songs are literary, yes, and they are undoubtedly masterful works of art, but they are not literature. They aren’t written to be read, they are produced to be listened to; however, what was refreshing about the pick was that it reaffirmed the Nobel’s commitment to newness and ascertaining a place for the literary in contemporary society.

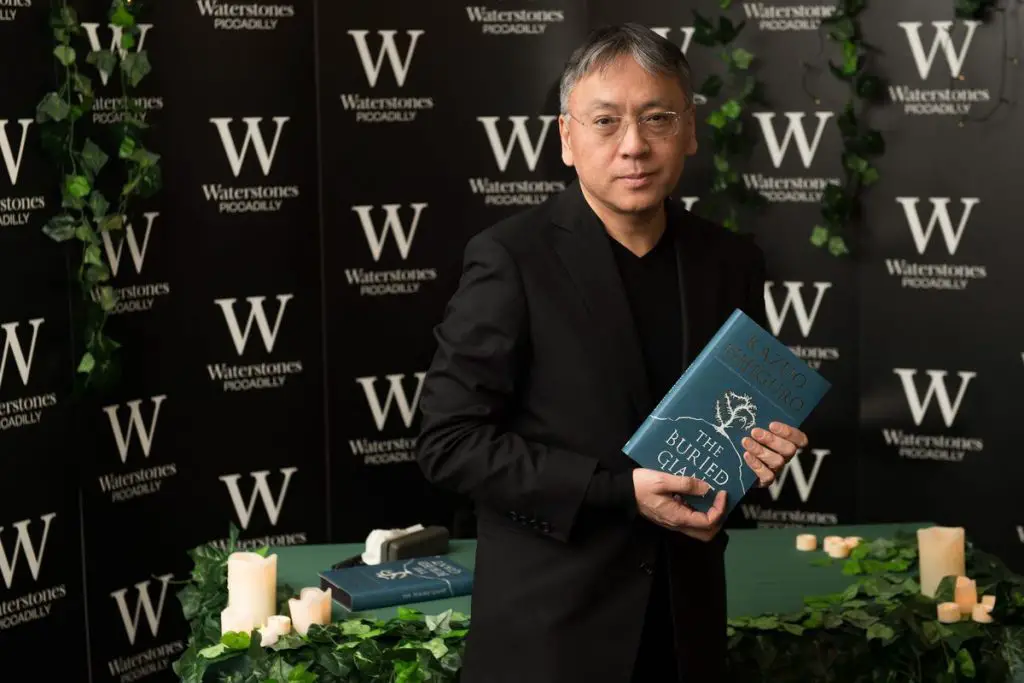

This year’s award, which went to the Japanese-born British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, an internationally best-selling author (those Eastern Europeans have nothing on Ishiguro’s sales), represents the best of what the Nobel Prize in Literature has to offer. Ishiguro is an undisputed master of his craft — read “The Remains of the Day” and you’ll see how much control he exerts over his considerable powers.

Ishiguro is a master of crossing genres, publishing everything from historical fiction to science fiction and fantasy. It may seem strange to gush over something as basic as name recognition, but it’s highly uncommon for a writer of Ishiguro’s appeal in this day and age to ever win, especially for a writer who blends genres as much as Ishiguro does.

I think Ishiguro’s Nobel Prize represents a turn away from the ivory tower towards the masses whose tastes are variegated and tinged by technological and global advances. Ishiguro himself is a transnational figure, a suture shutting close the gap between East and West, and his works such as “Never Let Me Go” are colored by the digital age. In awarding Ishiguro his Nobel Prize, perhaps those whose literary inclinations might not dovetail with the Nobel Committee’s will see a literature they recognize being taken seriously and encourage renewed interest in an award whose prestige and influence is undeniable.

I, for one, don’t believe in proclamations of literature’s imminent death. It is an art that has endured for millennia and will endure for millennia more, but only if it submits to the will of its own mutative potential. The Nobel Prize in Literature, after all, was established on the principle of change and, by continuing a tradition of literary innovation, will no doubt play an important role in pushing the literary landscape “in an ideal direction” for years to come.