On a Wednesday evening, my friends and I found ourselves in handcuffs.

A night out drinking had turned into a terrible mistake. Displays of public intoxication at Fenway Park must have landed the four of us in this drunk tank, yet we had no memory of it. We couldn’t even remember who won the game, but that was the least of our concerns. Because even though being locked in a cell was unconventional, this particular cell was disturbing.

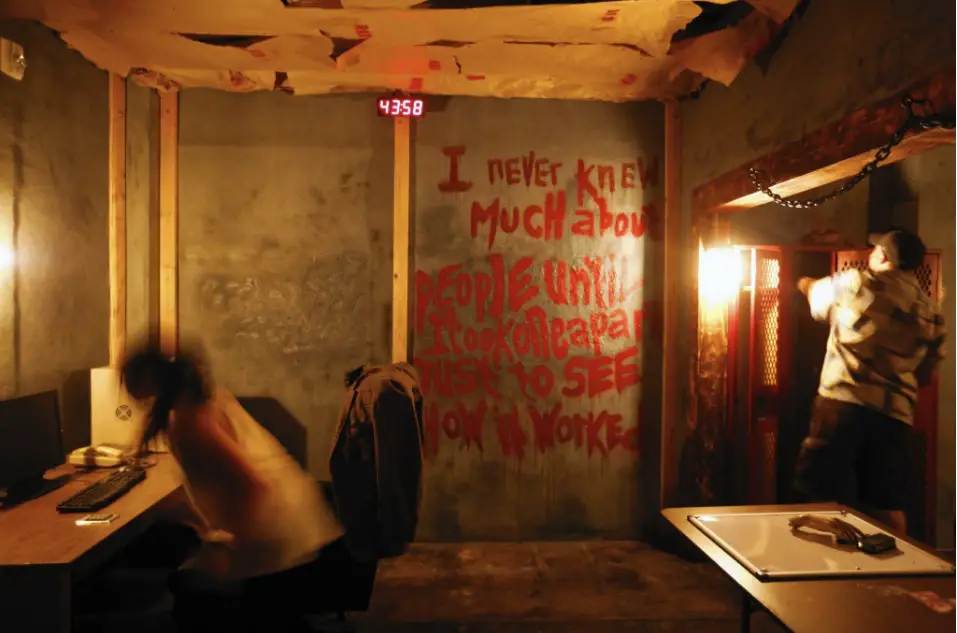

Blood-red scrawls and cries for help painted the cell’s walls. The sheets on the metal bunk bed were torn and stained. Outwardly pointless numbers were everywhere. And there was no guard. It was just the four of us, handcuffed to each other, in a mostly bare cell.

A television we could see through the cell’s bars lit up shortly after we took in our situation. It displayed a timer. 60:00 it said. Then 59:59. Then 59:58. We turned to each other.

“So,” one of my friends said. “Where do we begin?”

In a recently new phenomenon known as “escape the room,” scenarios like this aren’t unusual. The objective is seemingly simple. Get out. But challenging puzzles, unexpected twists and poor communication skills often leave the participants helpless to the timer’s relentless countdown. The room triumphs, and the losers leave to have their photographs taken with handheld signs informing those on Facebook that they were trapped and in need of pizza or in need of smarter friends.

But despite most participants leaving the room as losers, devastation and disappointment do not afflict the players. Rather, their failure leaves them giddy and with a thirst for more of these trials.

The idea behind “escape the room” is not new. In literature, a similar gameplay mechanic is sometimes seen in short stories and “choose your own adventure” books; the hands-on start of the experience is said to date back to the start of interactive text games when John Wilson wrote a computerized text adventure called “Behind Closed Doors” in 1988. In his story, the main character is trapped in a single location—an outhouse—and the player has to make decisions to help the character get out.

This gameplay mechanic has since evolved drastically. Hundreds of PC games that follow this formula—you’re trapped in a room with one exit, find the clues to escape—have been created and available to play on any computer. They are often minimalistic, accompanied by eerie ambient music and lacking other characters, successfully evoking a sense of isolation and sometimes panic as the player attempts to find clues in the room that will earn them their freedom. These games grew wildly popular during the 2000s and became inspiration for real-life versions later in the decade.

Takao Kato of Kyoto, Japan created the first real-life, in-person escape game in 2007, where he found there was the opportunity to have more freedom and creativity with the puzzles players could attempt to solve that a PC game simply couldn’t allow. But it doesn’t venture too far from the PC games. Rather, it’s like the player is being immersed into an actual video game, but they are unhindered by limiting game controls.

“When people are trapped with people they don’t know with challenges to solve, they are free to get really into it because they have control on the adventure,” Takao Kato wrote on his website. “When confronted with time limits and confined spaces, people think outside of the box and really have a blast.”

“Escape the room” games have spread across the world, with many locations scattered throughout the United States. Most places charge around $25 a person for a one-hour room challenge, typically maxing out the room with ten people.

Though it varies from company to company, most will offer clues or advice if the players get stuck or require assistance. A “gamemaker” is also always watching the players in the room via videocameras, so if someone grows uncomfortable during the experience, they can let that person step out. Unfortunately, those with small bladders are warned that the doors won’t open for bathroom breaks.

My friends and I were unable to escape the drunk tank that night, but the giddy high we had from the experience stayed with us on the subway ride home. This was our fourth time playing an “escape the room” game and always after the experience, the four of us found that we could talk about it for hours. If only we had done this instead! We were so close to figuring out this puzzle. Oh my god, I can’t believe we had to remove the mask from that man’s face.

The adrenaline rush stays with the player well after the time runs out. But the thrill of the game doesn’t just come from playing it. It comes from the build-up—the excitement of not knowing why exactly you’re paying someone to lock you in a room for an hour. You’re thrown in the room with nothing except maybe a simple backstory. From there, your freedom is completely in the hands of you, your friends and complete strangers.

And it’s crazy how much fun that can be.

Maybe it’s a desire to be like the superheroes and crime fighters we read about and see on television that draws players to these rooms. Maybe it’s a desire to put down the game controller and step into a real-life game instead. Or maybe it’s just a desire to spice up our normal lifestyle a bit.

On his website, Takao Kato says, “I often think that the normal life we lead could become meaningful if we changed how we look at it. Imagine if there was a secret code underneath this desk, or if a key was hidden under the sofa, or if the young man next to you had a secret letter. If you look at the world as if it were an adventure like this, I think it would be kind of nice and mysterious.”

Whatever the reason is behind the “escape the room” draw, the popularity surrounding it does not appear to be vanishing. The thrill of trying to escape is addicting. And playing the game once is sure to entice you to try again.