Nov. 4, 2008, was one of the most pivotal days in modern American history. On the night of the fourth, the United States elected its first African American president, a feat that seemed impossible a few years earlier. In a country reeling from the difficulties of a financial recession and a seemingly directionless war on terror, Barack Obama’s imminent ascension to the presidential office was a faint glimmer of hope for many across the country.

While millions were overcome with jubilation, the day was one of loss for the LGBTQ+ community. The political merits of the general election were quickly overshadowed by the passage of California Proposition 8, which promised to ban same-sex marriages in the nation’s most populous state. Across California, outraged and grief-stricken protestors took to the streets expressing their disgust for the ballot initiative.

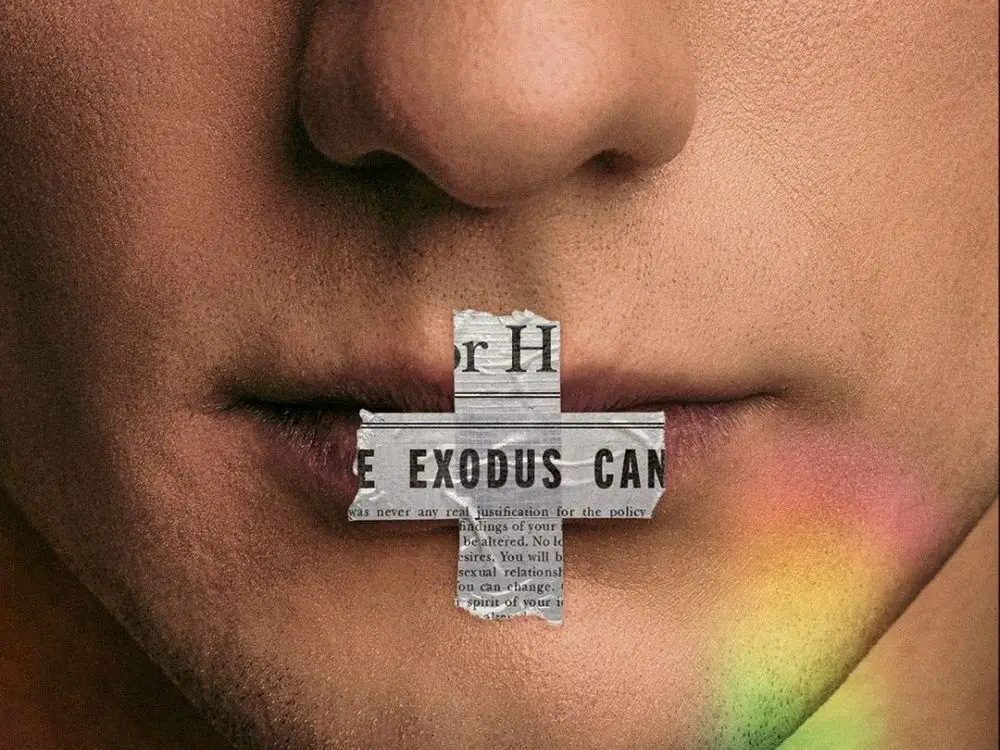

As with any sizeable protest, news cameras were dispatched to the scene, and the footage they captured depicted a profoundly sorrowful atmosphere. The evocative news footage of the vigils occupies a central place in Kristine Stolakis’ new Netflix documentary “Pray Away,” which incorporates it as a contextual tangent to its historical account of conversion therapy in the United States.

Proposition 8 was eventually found to be unconstitutional in the court system, yet this victory was only a marginal step toward addressing the cultural bigotry that has scarred the LGBTQ+ community for decades. The pseudoscientific philosophy of conversion therapy has always overlapped with the root justification of homophobic legislation, yet conversion therapy has slid under the public’s radar for decades. “Pray Away” seeks to shed light on this shadowy dimension of American life, providing survivors and former perpetrators of conversion therapy with a platform to display the long-term consequences of the subject’s low profile.

Conversion therapy is a body of thought and training positing that homosexuality is unnatural and individuals who feel same-sex attraction can become heterosexual through adherence to specific tactics. The film contains many clips of organized retreats where participants listen to speakers, share their own stories and partake in gendered activities under the guise that these behaviors can fabricate heterosexuality.

Contemporary psychologists almost exclusively condemn the practice as pseudoscientific and note the heightened prevalence of suicide among participants in conversion therapy due to feelings of inadequacy and guilt. “Pray Away” seeks to infuse the dialogue around conversion therapy with the perspectives of those who were formerly in close proximity to it using a simple yet effective format.

The film starts by profiling Jeffrey McCall, a man who is shown standing in front of a supermarket offering to share his story as a formerly transgender woman to passersby. Some show disinterest, but eventually, one older couple stops to pray with McCall and express interest in his mission to convince members of the LGBTQ+ community to follow God’s intentions for sexual orientation. The film then cuts to establishing shots of interviews with men and women much older than McCall who proceed to introduce themselves as former organizers of conversion therapy or spokespeople for religious nonprofits that were proponents of the practice.

Over the next 90 minutes, the members of the newly introduced group become guides through the murky waters of conversion therapy, shining a light on specific facets of the practice that they are most acquainted with. One of the most informative interviews is Yvette Schneider’s, which entails a discussion of her previous work as a spokesperson at Family Research Council, a conservative lobbying group. She explains how the AIDS crisis of the 1980s occurred during the ascension of conversion therapy and legitimized its premise due to the perceived danger posed by homosexual relationships.

Unlike many of the other figures whose former careers are profiled, Schneider’s televised monologues on homosexuality are coursing with a thinly veiled vitriol that utterly demonizes the LGBTQ+ community. While she previously spoke with such conviction, the gravity of her words has come back to haunt her, a common theme for the film’s subjects as they reckon with the harm they have done.

“Pray Away” spends a significant portion of its run time exploring the semantics of conversion therapy, as the practice has always selectively used language to portray its mission as a wholesome endeavor. To align itself with conventional therapeutic sciences, conversion therapy organizations use terminology such as “lifestyle” and “confusion” in reference to same-sex attraction to imply that homosexuality is changeable and can be “fixed.” The film includes grainy seminar footage from the 1990s in which these words and their synonyms are used by numerous spokespeople, who oftentimes claimed to have fully abandoned their same-sex feelings.

One of these individuals is John Paulk, a representative for Exodus International. The now-defunct Exodus International was a Christian organization that propagated the view that conversion therapy was effective. Paulk was noteworthy for marrying a former lesbian and having children, parts of his life that quickly turned him into the poster child for sexual conversion. In 2000, Paulk was spotted leaving a gay bar in Washington, D.C., and was subsequently sidelined from his work. He left the ex-gay movement in 2003, eventually embracing his sexuality and becoming comfortable with criticizing his former career.

Upon reflecting on his years as a champion for conversion therapy, Paulk states, “In some ways, I didn’t see myself as a gay person anymore … I based being gay on behavior. It was the behavior that made you gay, not your feelings.” The juxtaposition of Paulk’s old life and his acceptance of his dishonesty perfectly encapsulates the transformation that all the former conversion therapy advocates demonstrate throughout the documentary.

Much of the film’s duration is a retrospective on figures and organizations that are no longer active, yet — as the introduction demonstrates — there is a need to evaluate the current state of conversion therapy. The film does this by sporadically shadowing McCall, who continues to organize gatherings for ex-gay parishioners who share his evangelical beliefs in honoring God’s word.

The contrast between his contemporary religious fervor and the 20-year-old footage of fundamentalist Christian seminars builds a sense of a timeless, internalized prejudice that continues to plague many individuals within the LGBTQ+ community. McCall appears resolute, yet the conversations with former believers in conversion therapy demonstrate how fragility can lurk just beneath the facades required by the practice. Julie Rodgers is a younger survivor of the Christian ex-gay machine who began her road to self-acceptance when Exodus was closed in 2013.

The organization dissolved following several clinics that Rodgers and others associated with Exodus attended in which survivors of conversion therapy shared their trauma and condemnation of the practice. She recalls how “it was the first time that I identified more with the survivors sharing their story than I did with anybody from Exodus.” In addition to her interview, the film documents her wedding planning and ceremony, symbolic moments of resolution and peace that can be seen as a triumph over a system that intended to distort her.

“Pray Away” consistently demonstrates that the pseudoscientific principles of conversion therapy are false, yet it does support the validity of another type of conversion. The profiles of former leaders in the ex-gay movement demonstrate that the beliefs propping up the practice can be abandoned. Alan Chambers, the man who led Exodus when it closed in 2013, sat alongside Julie Rodgers at the survivor clinic and is one of the people interviewed for “Pray Away.” His willingness to express profound guilt and regret on camera only eight years after he was the largest figurehead for conversion therapy is remarkable and the most moving component of the film.

The pain that arrests his demeanor while speaking about his career is identical to that of all the interviewees, and their earnestness to dispel the lies they told means their grief is not in vain. Many of the large, Christian organizations that fought for conversion therapy have disappeared, but grassroots efforts to continue its doctrine still prevail. The practice is far from gone, but the resilience and growth that “Pray Away” embodies offers hope that change is possible and inevitable when people are empowered to embrace their identities.