The places I find myself missing the most during quarantine are art museums. I miss the stillness inside a gallery, the respectfully curious atmosphere that surrounds me as I wander from painting to painting. Recently, I’ve been going to some online art talks through the Whitney Museum, and I rediscovered my love for the work of Yayoi Kusama.

I learned about her in my high school AP art history class, and I was enamored with her quirkiness and journey to fame. Her work seems even more timely now, during a pandemic that has wreaked havoc around the globe. Her paintings, sculptures, and famous Infinity Mirror Rooms show insights into repetition, meditation and absurdity. With her strange fixation on dots and elementary use of color, her works yield a sense of acceptance and peace amongst the chaos.

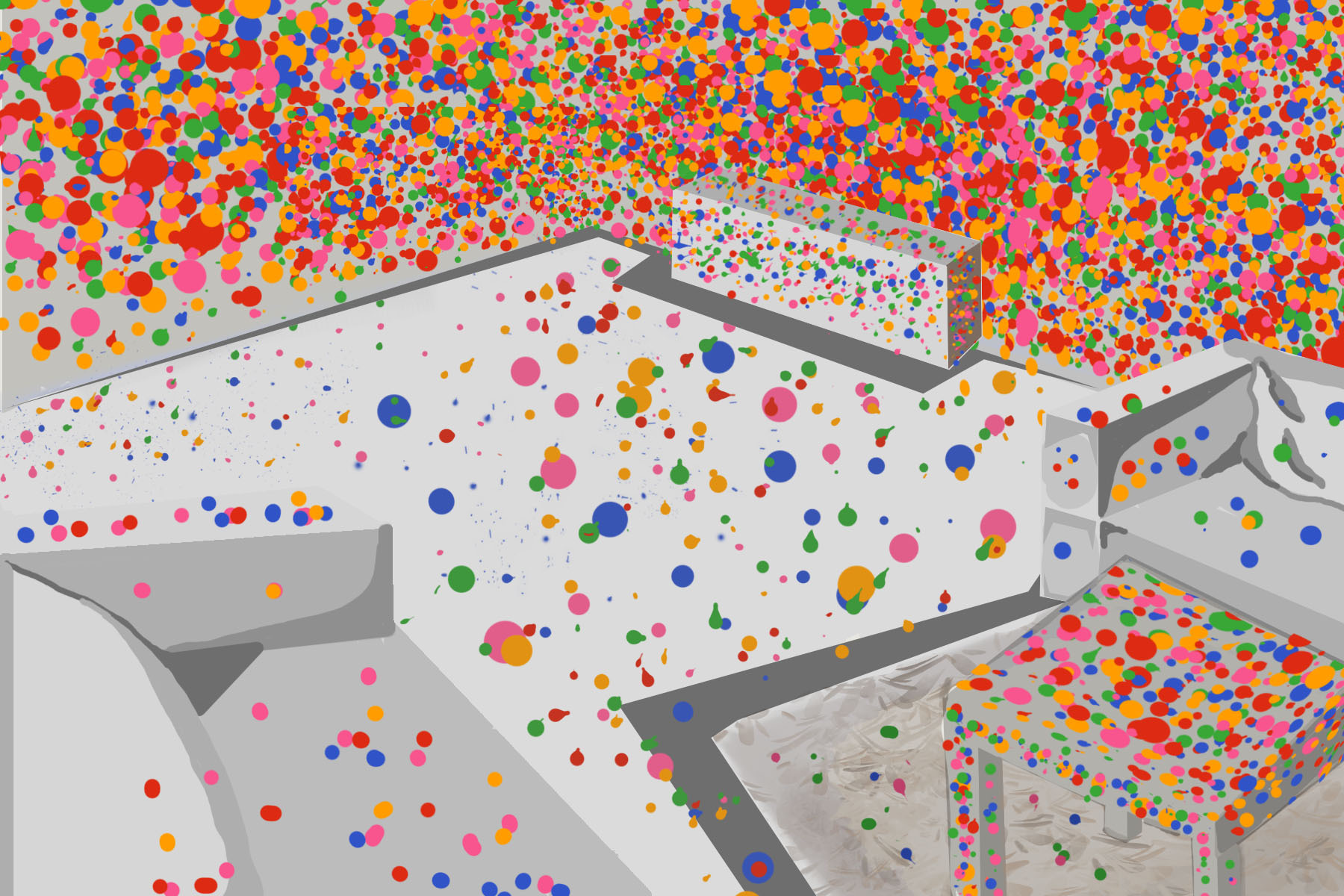

The first time I saw Kusama’s art was in 2017 at her “Festival of Life” exhibition at the David Zwirner Gallery. The estimated wait time to see her famous Infinity Mirror Rooms was five hours. Giving up on the long line, I wandered into Kusama’s 2D paintings. Massive panels of colorful abstraction lined all four walls, and in the center of the exhibit sat a sculpted flower, as if one of her creations had jumped straight off a canvas.

I was immersed in the colorful panels until the gallery was about to close, and last minute, I jumped in the line for her 3D work. When I finally entered her renowned Infinity Mirror Rooms exhibit, I lost all sense of self in blinking lights and floating orbs, as my eyes peered into the reflective endlessness. Viewing each room was limited to a minute per patron, so I was left alone to marvel at the blinking dots for a moment by myself. If you’ve ever looked into one of her works, you know how ethereal, personal and unearthly it feels to look into her mirror rooms.

The thing that struck me was how simple, yet psychological her artwork is. Her obsession with polka dots and pumpkins is whimsical, but also a bit eerie. Even her appearance, as a little old Japanese lady who wears an eye-catching red wig, is full of contradictions. Everything about her is loud, yet she speaks quietly. Kusama is original, self-made and undeniably wacky, just like the artwork she’s known for. When I look at her obsessively repeated dots and paint strokes, I feel a sense of peace within all the visual commotion.

Kusama’s background is unconventional. Born in 1929, she grew up in a wealthy Japanese family where her father was a womanizer and her mother was abusive. With the help of famous American artist Georgia O’Keefe, she escaped to New York where she thrived for 16 years.

She immediately became an influential figure in the pop art and conceptual art scene that was gaining traction with figures like Claes Oldenberg and Andy Warhol. She was open about her history of mental illness, beginning in her childhood with visual hallucinations of dots, and her lifelong anxieties. Her art gives her a way to create something beautiful from the things that haunt her.

Infinity Net Paintings

Even though she’s known most for her “Instagrammable” Infinity Mirror room installations, she’s had almost four decades of work preceding the 21st century. Her ongoing series of Infinity Net paintings are what first brought her fame. These pieces seem monochromatic from a distance, but when you move closer, you see the tiny marks that are made with obsessive precision. Kusama’s textured brush strokes are neither random nor calculated but the intricacy creates a sense of overwhelming endlessness.

She describes her work as “very large canvases without composition—without beginning, end, or center,” as if these colorful nets could expand out infinitely beyond the edges of the paintings themselves. Her first solo show at the Brata Gallery in 1959 incorporated a huge white-on-white Infinity Net painting, which not only reflected her personal hallucinatory visions of dots, but represented the invisible netting that separates us from others, and sometimes even us from ourselves.

There is something ridiculous about how intricate these monumental paintings are. I imagine the painting process to be meditative as each small brushstroke is made with the idea that it is only significant in its role in the large scheme of dots. Kusama says she often creates these pieces in 50- to 60-hour stretches, in a trance-like process she’s called an “indescribable spell.”

Accumulation Sculptures

Obsessive repetition continues in her three-dimensional series “Accumulations” in the 1960s. Her piece “Accumulation No. 1” consists of an armchair covered in small stuffed phallic sculptures created from white fabric. The repetition of this male form is both aggressive and humorous, and the process allowed her to overcome her sexual anxieties.

Many of her three-dimensional soft sculptures at this time are similar to those of Claes Oldenberg, who was known for making super-sized pop art sculptures. Her first Infinity Mirror Room, “Phalli’s Field” (1965), was a 25-square meter room with the floors covered with hundreds of the same stuffed white phalli motif, except this time, she covered them with red dots.

The phallic forms were mirrored over and over in the Infinity room, multiplying her fear to an impossibly large yet hilarious scale. Her fear of patriarchy and male sexuality is turned into something both light-hearted and therapeutic.

Happenings in NYC, Infinity Mirror Rooms

Kusama was also known for her activism, staging “happenings” in the 1960s and early 1970s, where she directed anti-war and anti-capitalist nude demonstrations at locations like Wall Street and the Brooklyn Bridge. She returned to Japan in 1973 and laid low in the international art scene for a few decades, choosing to live voluntarily in a mental hospital to treat her neurosis. In the 2010s, she made a huge comeback, spurred by a major retrospective in 2011 and 2012 at the Whitney Museum in New York. Her “Infinity Rooms” became a part of the “Instagrammable” sightseeing trend. Mirrored rooms like “Fireflies on the Water” (2000) and “The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away” (2013) are made up of LED lights floating in the dark, reflected against mirror after mirror after mirror, seeming to go on forever, in a space that’s so obviously finite.

When I saw her exhibit in New York, the experience felt extremely personal. Surrounded by an unearthly view, my self-awareness slips away as I lose myself in the shimmering dots that seem to go on forever. There is no end in the Infinity Mirror Room. To me, it felt like a sort of aesthetic sensory deprivation tank; I was floating in the mind of Kusama and her idea of what the universe really looks like, and how insignificant we and our problems are in the grand scheme of things.

When Kusama made her past works, paintings of repeated dots or sculptures of repeated form, she always described the process as obsessive and simultaneously introspective, a sort of meditation for her to cope with her mental illnesses. Her Infinity Rooms are a way for her to communicate her experience of art-making to us, as we experience the infinite calm and absurdity of her mirror rooms.

In the midst of the pandemic, as every system we thought of as secure — from our public health systems to our police departments to our political institutions — is falling to pieces, Kusama’s art shows us that she’s always known that our sense of control was a facade.

She’s been pointing out the foolishness of petty everyday worries ever since she started making art, and she’s shown us a way out: By allowing ourselves to let go and understand our minuscule existence, we can let go of our own anxieties and work toward something better. When we can see how ridiculous our reality is, it’s easy to realize how funny, petty and absurd our everyday stresses are.

Her Infinity Rooms are just physical representations of a mindset, a mental space where we are free to see the infinite truth beyond ourselves. As Kusama says, “Our earth is only one polka dot among a million stars in the cosmos. Polka dots are a way to infinity.”