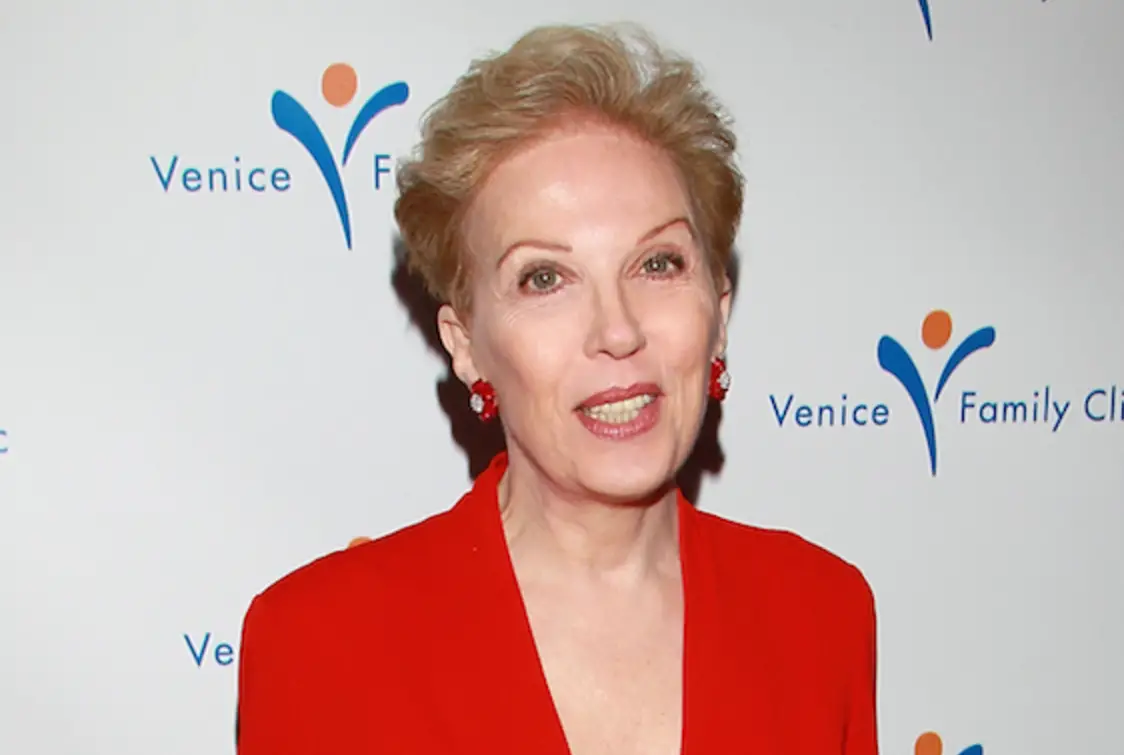

On Sept. 13, “Dear Abby,” the advice column in newspapers around the United States, featured columnist Jeanne Phillips’ response to a man who wanted to start a family with his wife but was struggling to agree with her on names for their future children. The mother, who was born in India, wanted their children to have names that speak to their ethnic roots. The father wanted their children to have Western names, ones that would be considered normal in the United States. And Phillips agreed with the father.

In the “Dear Abby” column, Phillips published her explanation about why she sided with the concerned husband. She said, “Not only can foreign names be difficult to pronounce and spell, but they can also cause a child to be teased unmercifully.” She continued, “Sometimes the name can be a problematic word in the English language. And one that sounds beautiful in a foreign language can be grating in English.” Phillips, who goes by pen name “Abigail Van Buren” or “Abby,” received backlash for her advice.

You would think that by now, Americans would be more accepting of other cultures and not feel the need to anglicize the names of those who live here, but evidently, some people do not feel that way. The “Dear Abby” column was first published in 1956, and from its recent publication, it is clear that the column maintains the mentality of the ’50s.

In 1956, the most popular baby names in America were Mary and Michael. Although these names are Westernized, they, like most other names, come from other cultures and languages. Without this foreign influence, many American names today wouldn’t exist. Names heard in classrooms and conference rooms and displayed on office doors all over the country today were once foreign several years ago.

What Phillips fails to consider is how much thought parents put into naming their children and how much those foreign names can mean to the parents. Every name has a meaning, and every child was given a name for a reason. If parents are putting careful, loving thought into selecting their children’s names, why shouldn’t they be able to make that decision freely?

Hearing about Phillips’ response in the “Dear Abby” column made me think about my own name and how it was chosen. One of the memories I cherish the most is hearing the story about how my parents chose my name and how much thought they put into naming me. My parents, like the couple in the column, argued about what name they should give me. My mother suggested name after name to my father, and he kept responding with resounding noes. After quite some time mulling through names, they finally came across one they agreed on, Kaitlyn. They were pleased with the meaning. It means “pure,” deriving from the meaning of the Greek word “katharos,” and it is the Gaelic form of the name Catherine.

Upon their announcement of what my name would be, another argument ensued: how to spell it. My grandmother and aunt argued about which spelling would reflect my Irish roots the most. One of them claimed it was “Caitlin”; the other said it should be “Kaitlin.” Eventually, my parents decided on Kaitlyn, a variation not as traditional as others. It was the American way to spell my name, but they liked it.

My family wanted my name to show who my ancestors were and, in turn, show who I am and who I was to become. My name is Irish-American, as I am. I am proud when people see or hear my full name and say, “Can’t get more Irish than that!” or “Ah, Irish girl you are.”

For me and many others whose names are a central part of their identity, Phillips’ remarks in the “Dear Abby” column hit home. If a parent wants to give their child a name with a meaning behind it, why should anyone object to such a wish?

It was unjust, then, for columnist Phillips to rhetorically ask, “Why saddle a kid with a name he or she will have to explain or correct with friends, teachers, and fellow employees from childhood into adulthood?”

Any child who is given a foreign name will one day have the ability to reflect about their origins. They will know they were brought into the world with their historical legacies in mind. Someday, they might have the opportunity to give their own children names reflective of their culture.

Of course, the parents must agree on the name they wish to give their baby, and this can be problematic when the parents come from different cultures and want their children’s names to be reflective of that culture. In the situation of the man who wrote to the “Dear Abby” column, he and his wife had different views about what kind of name their son or daughter should have. Their children will share their DNA — one part the mother, one part the father. The children’s identities should not reflect one parent more than the other, especially if both parents do not agree.

Perhaps Phillips believed their argument would arrive at a resolution if they settled on a more traditional name and gave their children Indian middle names, as the father suggested. Maybe she made her suggestion because she genuinely thinks they would benefit from having names others can easily pronounce.

Whatever her intentions were, Phillips failed to acknowledge the fact that this country is a land of many cultures and people who wish to celebrate them. By siding with the husband, Phillips is sending the message — not only to the wife but to readers everywhere — that diversity should not be celebrated in America.