It’s basically a truism at this point that American political discourse is in a rough place. Liberals and conservatives fail to see eye-to-eye on almost anything, and there’s an ugliness to political language that (allegedly) has never been this bad before. Amid all the nastiness, it’s comforting to know that plenty of shows worth watching can explain serious current events with a humorous touch.

Satire of the news has a long history, but since John Stewart’s tenure at “The Daily Show,” its role has morphed and expanded: Stewart’s writing team and often astounding use of archival footage gave satirical news a reputation for investigative journalism and witty truth-telling. As early as 2004, some admitted to using “The Daily Show” and its imitators as their primary source of news, and Pew Research found that 12 percent of Americans cited it as their main source by 2015.

After Stewart retired, the market exploded with satirical news shows, with “The Nightly Show,” “The Opposition,” “Last Week Tonight” and “Full Frontal” being some of the biggest examples. Those that have survived provide incisive, funny and very informative current event analysis, effectively filling the post-Daily-Show-Colbert-Report void.

But what if the popularity of political news satire has something to do with the rise of rigid partisanship and dysfunctional democracy? These political satire shows have the uncomfortable tendency to accomplish the opposite of what satire should do.

For a classic example: Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” satirized England’s lack of response to the Irish famine by (ironically) pointing out that the Irish could just eat their babies, thus solving both the overpopulation and famine crises at the same time. Swift intended to shock English readers out of complacency.

But regular viewers already know what they’re getting into when they turn on “Last Week Tonight.” The majority of these shows share a liberal political bent, so, more often than not, they wind up bolstering their audiences’ beliefs instead of challenging them.

I find this aspect of satirical news very troubling. Although late night comedy features mostly liberal hosts, conservative news satire exists as well, and the self-reinforcing nature of these bubbles of news sources cause the national conversation to become both sides talking past the other.

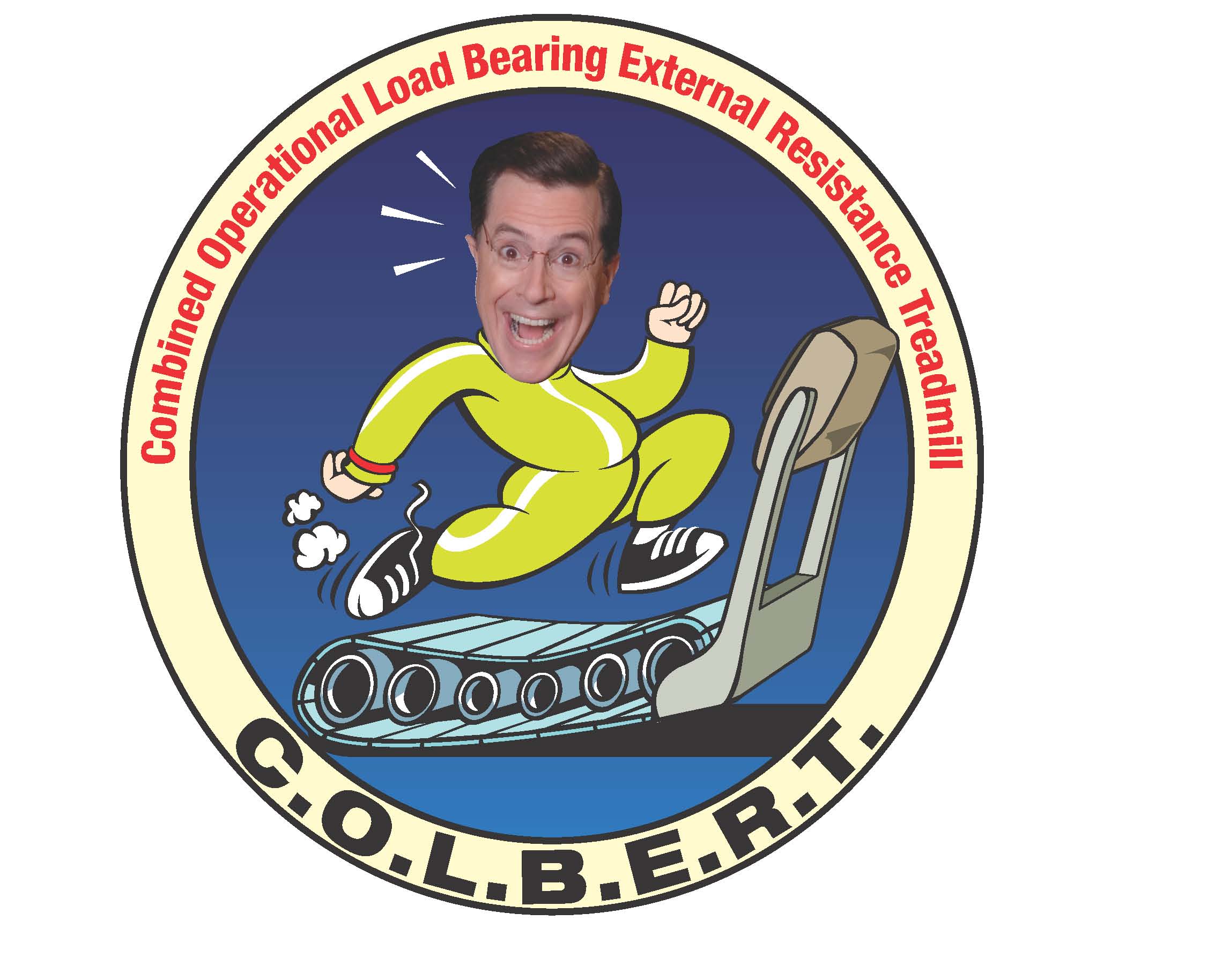

When comparing them to traditional news sources, satirical programs have a surprising ability to explain complicated subjects. A 2014 study at the University of Pennsylvania, for example, found that viewers of “The Colbert Report” understood campaign finance better than viewers of any other cable news source. But if viewers in different bubbles don’t listen to each other, how effective is that knowledge, really?

The apathy inspired by political satire also unsettles me. When viewers rely too heavily on satirical sources for news, and those sources only ever satirize the political process, they reasonably conclude that the political process is either ineffective, corrupt or ridiculous.

A recent segment of “Full Frontal with Samantha Bee” that compared the special counsel’s investigation into Trump’s presidential campaign to the Watergate investigation fully displayed that nihilistic tone. Using sound bites from both Nixon and Trump, followed by a testimony from a Watergate expert, Bee established that the two investigations had striking similarities. Then she said the checks that limited Nixon’s executive power all appeared to be either inactive or neutered in Trump’s case.

A former executive producer on “Full Frontal,” Jo Miller, claimed in 2017 that the show didn’t have a partisan tilt. Miller left the show later that same year, but even if the show was or still is politically unbiased, messages about how nothing can be changed to hold politicians accountable are anything but constructive for a democracy struggling with voter turnout. The end result creates a viewer with a good grasp on the issues lacking the hope or perspective needed to solve them, and that kind of fatalism poisons democratic discourse.

“Last Week Tonight” notably attempts to avoid this kind of hopelessness; along with actions targeting a number of other issues, host John Oliver turned heads by flooding the FCC website with comments on net neutrality and wrote an Amazon bestselling children’s book about a gay pet rabbit. In the long term, it’s hard to say if either of these pushes translated into real-world results — net neutrality rules were officially repealed in June, for one. Put that into context with the dozens of times Oliver has ranted at Trump on his show, and it just becomes another example of how one-sided satire fails to reach anyone not already interested.

It’s worth noting that most hosts don’t want you to characterize their shows as “news.” Stewart, Oliver and Bee have all rejected the idea that they are journalists or news-people, but political satire now includes searching archival footage, conducting interviews, fact-checking and high-level policy explanations. If that’s not real journalism, what is?

I don’t think political satire will die out anytime soon — and it shouldn’t. Satire is actually a healthy part of a functional democracy, capable of making people uncomfortable about positions they were previously convinced of, and that’s exactly what the political conversation needs more of right now. Unless it can find a way to break out of playing to familiar crowds, though, it might just continue making things worse.