In an age of informal segregation, capitalism-fueled climate crisis, soaring housing prices and an ever more precarious precariat, it shouldn’t be a surprise that many are clamoring for a change to the American economy. The government has been glacially slow in meeting these demands, struggling to follow through on the Green New Deal and refusing to increase the minimum wage despite wide public support. Under these circumstances, some localities have decided to take matters into their own hands by minting their own currencies.

These complementary currencies are not meant to replace the dollar. Instead, they work alongside legal tender, subsidizing the income of those who may not be earning a living wage. Though complementary currencies can be implemented on a regional or national level, they are most often ultra-local.

Here’s how it works: You do an hour of work and receive a specified amount of complementary currency. You can then spend that complementary currency at local businesses, including grocery stores and transportation companies. If you decide to spend your complementary currency at a local restaurant, then that restaurant can use the currency to pay its employees or to buy goods or services from other local businesses that accept the currency. Essentially, complementary currency is just a very limited, localized version of legal tender. Because it can’t be used at national or international corporations, complementary currency encourages those who use it to spend locally and keep wealth in the community.

Complementary currency is not a new idea. From 1690 to 1775, there were various complementary currencies minted throughout the American colonies in order to ameliorate the consequences of a shortage of British money, which was the legal tender at the time. In times of economic hardship since then — or even before then, outside of the United States — complementary currency has appeared alongside legal tender to help soften the hard times. During the Great Depression, complementary currency was at an all-time high, issued by corporations, communities, barter clubs, banks and even local governments.

It should come as no surprise, then, that complementary currency saw much success during the Great Recession in 2008 — and some of them have stuck around until now. The most notable of these is the BerkShare, minted in Berkshire County, Massachusetts. This community of 19,000 has managed to rally 400 local businesses to participate in the exchange of the BerkShare since its inception in 2006. There are now at least 140,000 BerkShares in circulation, all of which are exchangeable for legal tender at various banks in the area — 100 BerkShares can be exchanged for $95.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BAitMZpkoeb/

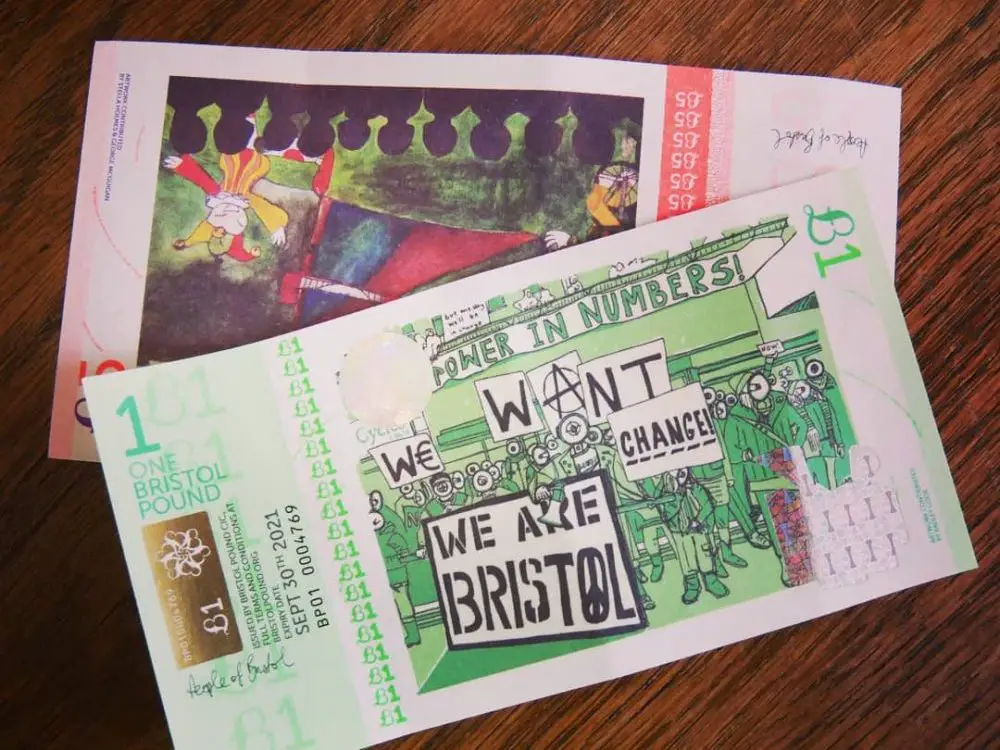

Businesses accept BerkShares at face value, i.e. 10 BerkShares is equivalent to $10, providing community members with an incentive to use their BerkShares instead of exchanging them. BerkShares come in physical bills that are somewhat similar to cash, with an image of the rolling hills that characterize the county, portraits of several important local historical figures and varying shades that denote the worth of the bill.

Some communities are propelling complementary currency even further into the future. The Hudson Valley Current, a complementary currency local to the Hudson Valley in New York, is completely digital. Community members are able to pay simply by sending a text message, which makes the currency inclusive to those who may not have a smartphone. The lack of physicality makes the currency much less clunky and leans into the overwhelmingly popular trend of digital payment methods such as Venmo or PayPal.

Community members can earn up to 5% of their paychecks in Currents, and businesses can opt to receive Currents as either full or partial payments for goods or services. As of now, the Current is accepted at 100 businesses. No matter the fluctuations in legal tender, one Current is equivalent to one dollar, but unlike BerkShares, Currents cannot be exchanged for dollars, keeping the exchange of the currency entirely local.

Of course, the challenge is that a complementary currency only works if large numbers of individuals and businesses are willing to adopt it. In Pittsburgh, a company called involveMINT is attempting to get a complementary currency, TimeCredits, off the ground in impoverished neighborhoods such as Hazelwood and Braddock. The idea is that involveMINT will essentially hire long-term volunteers — ChangeMakers — to provide whatever service is needed in the community, whether that be composting food waste, growing fresh produce or tutoring children in underserved school districts.

These ChangeMakers will then be paid one TimeCredit, which is roughly equivalent to $15, for every hour that they work. Several local businesses have already agreed to accept these TimeCredits, but the road to a productive local currency is a long and bumpy one. It may take years for the TimeCredit to be up and running.

Even though it takes time and a whole lot of effort to launch a complementary currency into circulation, the demand for economic change remains, and overall the future of complementary currencies appears bright. In fact, the state of New York is currently considering a bill — the Inclusive Value Ledger — that would essentially create a statewide digitalized complementary currency.

The goal of this system, which would function like a “public Venmo” without any of the fees included on that platform, is to provide an easy and free way for low-income people without bank accounts to transfer money. In this way, the currency would ultimately stimulate circulation of funds and economic growth in those communities within New York that need it most.

Perhaps this sounds idealistic, but the proof is in the pudding — thousands of complementary currency systems have flourished throughout history, and plenty are still flourishing now. Of course, we haven’t seen anything quite on the statewide scale — yet — but with the implementation of new technology and a drive toward economic reform, more is possible than ever. Times are changin’, indeed, and we should not be afraid to change with them.