May is here once again, and so is Asian and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month. Originally signed into law as an official 10-day period in 1978, it eventually became an entire month by 1992. In the last few years, it has gained more public recognition as the collective confrontations with America’s disregard for people of color (POC) have continued to increase. It’s meant to be a nationally sanctioned nod of acknowledgment toward a historically marginalized group in America.

However, AAPI consists of many groups, and they encompass too many cultures to be sufficiently described by a generic umbrella term. A video from PBS shows there are multiple variations, such as AAPIDA (Asian American Pacific Island Desi American) and AANHPI (Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander). The fact that there are this many acronyms — and that they are complicated mouthfuls of letters — feels no more validating, at least to me personally. For me, it’s difficult to connect with AAPI Heritage Month for two reasons.

The first reason is that I have never liked having specifically designated months for POC, because they tokenize their identities and treat them like props. If there is anything these months really teach us, it’s that diversity sells — literally. For all of May, you can find a variety of AAPI-themed merchandise in stores everywhere. It lets companies feel good about supporting people of color by engaging in the national pastime of temporary conscience-clearing.

Professor Vanita Reddy raises an excellent point in a Q&A for “Texas A&M Today” about how multiculturalism can actually cause harm: “Multiculturalism does three things: One, it is the politics of recognition which is saying, ‘We see you as a non-white racial other.’ The second thing it does is celebrate differences, which is saying, ‘We celebrate your traditions as a non-white racial other.’ Third, multiculturalism tolerates this difference, saying, ‘I tolerate you because of those traditions and the way that they add value to making our society more diverse.’ So recognizing, celebrating difference, and tolerating difference are the three things that multiculturalism does.”

I had never considered how multiculturalism could be considered detrimental because the stigma against criticizing any mechanisms for diversity and inclusion is alive and well in America. As parents, educators and politicians continue to spar about critical race theory, the need for diversity is stronger than ever, but Reddy’s argument shows that if diversity is truly to be sustained in society, it must be done with care.

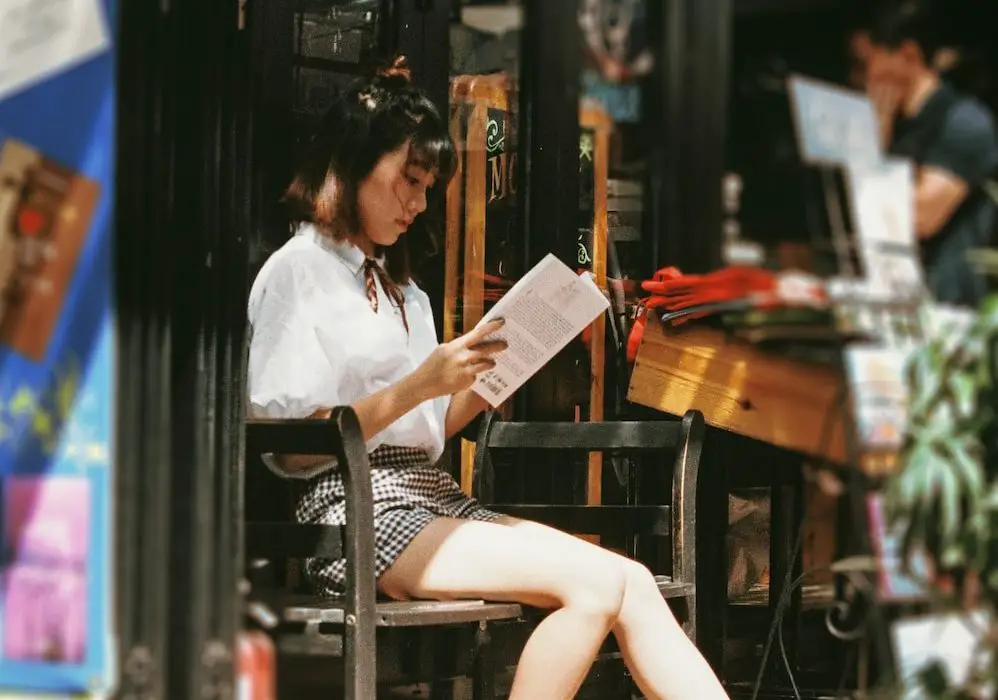

The second reason I feel indifferent to AAPI Month is because it tends to support entire AAPI cultures, presumably people of full AAPI heritage. As a half-Filipino woman, I should feel like this month is extending itself toward me too, but I have felt little to no attachment. When asked if I grew up with the culture — a question that is always asked about my Filipino side, not the Jewish culture of my white side — my answer is no. I don’t speak Tagalog. I rarely eat the food. I didn’t become a nurse and I’m not Catholic. Many common markers of Filipino heritage are scant or missing in me. Because of this, I feel like I have little to no rightful claim to my AAPI identity, especially when May comes around.

We may live in modern times, but some minutiae have yet to be tended to. I still occasionally have to check “Other” to mark my race on forms, and when I do, I hate not having enough options to describe what I am. When I wrote for the VCU chapter of “Her Campus,” we were trained on how to navigate the publishing software, and when filling out our profiles we were asked to list our race. The editor-in-chief noticed my confused look over the Zoom session and asked what was wrong. I felt almost embarrassed to pipe up that I was biracial — I was alone in doing so — and that there was no way to indicate this on the software (however, they did eventually enable that feature, and I take pride in having planted the seed).

Other times — though this is a relatively newer development — I have the opposite problem where there are too many options to describe what race I am. I get confused about whether I should identify as Asian or if I should be more specific and say Southeast Asian. I wonder if I even count as Asian American. I wonder if I count as a person of color because I am only part Asian or — because I am very light-skinned and pass for white — if I am barred from saying so. Who gets to decide the right answers to these questions, though?

Suffice it to say it’s a unique experience to be biracial because you have a wonderful blend of cultures shaping you. You are the embodiment of cultural exchange through love and family. However, it can also give you certain responsibilities that shouldn’t have to feel like yours alone, mainly to be equally well acquainted with the different sides of your heritage.

I recently spoke to my older sister and asked how she was feeling about this month. Every biracial person’s experience is different, though there can be some overlap, of course. She is the only person I know whose attitude toward biracial identity is similar to mine. Although she looks more Filipino than I do, we share the experience of passing for white while also balancing our Asian heritage. We agreed that we both experience indifference towards AAPI Month and that it really just feels like any month. This month is supposed to recognize our heritage, but its failure to resonate with both of us feels like a disappointment.

AAPI Heritage Month reminds me how I often feel like a statistic, something to be sold to. I don’t want my racial identity to be sponsored by Ulta Beauty, Spotify or Barnes & Noble when it already is fractured enough. I’m not arguing for ending the recognition of AAPI Heritage. What I am arguing for, however, is a more organic and legitimate incorporation of its celebration throughout the year. It’s worth considering how we can have it both ways. We can celebrate the history of people from everywhere and truly include everyone as we do.