Combat Partisan Politics in the Classroom

To what extent can a teacher’s political opinions show up in the classroom?

By Liam Chan Hodges, Franklin and Marshall College

You truly live in a time of enlightenment, for the archaic days of political philosophers, with their outdated theories and mental forays into the realm of idealized politics, are long gone.

The world has replaced such antiquated approaches with the insightful words of clickbait headlines, Snapchat news and whatever your “activist” aunt decides to share on Facebook. Anyone with half their fingers, three quarters of their brain and a semi-functional keyboard can scream political rhetoric into the abyss and reach a significant audience.

So, how do you filter through such a cacophony of views, the majority of which are either biased, unfounded or just fucking stupid? To whom should you turn for guidance?

For those individuals who are lucky enough to still be in school, whether it be college or high school, this answer should be simple. Teachers, professors, mentors and advisors serve as guides to point the way and provide the sieve with which to sift through the mess of voices that is American politics. And yet, if these are the individuals to whom young adults should look for guidance, the question remains, to what extent should these individuals impress their own beliefs upon their pupils?

The vast majority of issues in this country have become extremely partisan, yet it is a standard belief that those in education must abstain from partisanship. The reality is, though, there must be some issues which have definite right and wrong answers. Should professors not take a clear stance on these? Should they not express to their students when a line has been indisputably crossed?

The issue arises when it’s taken into account that all political and moral boundaries are relative. Every individual draws a line in the sand in a different place. There are certain actions that are cross-culturally sinful, such as murder, rape and theft, but even the ways in which these atrocities are dealt with are oftentimes hotly disputed, because every person is defined by a different moral compass.

Therefore, it would be nearly impossible for any professor or teacher to subjectively say that one thing is immoral or wrong, without in some way expressing bias. When it comes to teaching students and earning their respect and trust, bias is a most definite enemy.

Taking a trip back through time to the day following the election of President Donald J. Trump, I will illustrate an actual scenario that I experienced, wherein a group of professors exhibited such a bias.

The morning after America’s 45th president shocked the world with his devastating victory over opponent Hillary Clinton, reactions were mixed. Some celebrated, some mourned and others were indifferent, having long since given up all hope of a favorable outcome to such a divisive election, one that had long since made a mockery of American democracy.

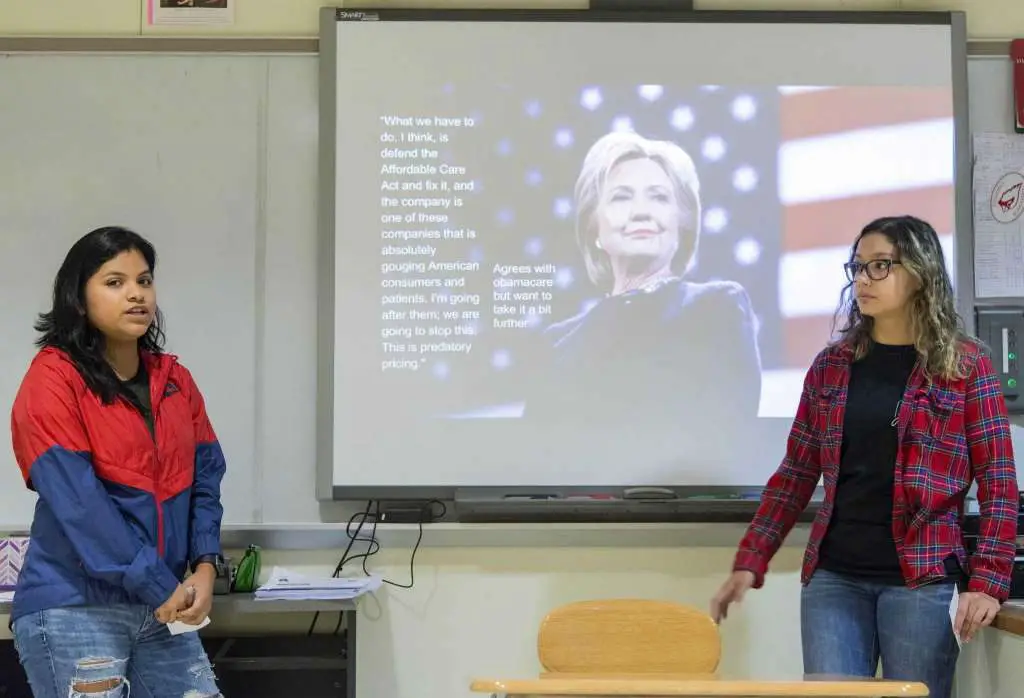

The issue throughout my campus was not so much the way that students felt, nor how they reacted to those feelings. For me, the issue arose when individuals who were supposed to act as objective academic guides responded in a way that was both unbecoming and unprofessional. Throughout Election Day and the few that followed, more than a few faculty members canceled classes so that students could participate in a day of grieving.

Though I voted against President Trump, such actions by the faculty rubbed me the wrong way. Had the election results been reversed and Hillary Clinton had been named America’s 45th president, I find it highly unlikely that those same professors would have canceled their classes as they did for Trump’s victory. This bias was so blatant that, in my eyes, it weakened the academic credibility of the professors who participated in such actions.

Yet, even as I write this, I have not completely convinced myself as to where I stand on this issue. If professors do take a backseat in politics, then they are simply the equivalent to encyclopedias or scientific instruments that can measure, analyze and recount facts, but cannot act in any way upon the present. To limit their opinions is to seriously hinder their ability to shape the generation of bright young minds that will follow them.

Though it may require making a political statement, should a professor of women’s and gender studies not take an open stand against policies that endanger women’s rights? Should those professors who lecture on constitutional law not bring to a student’s attention constitutional discrepancies in recent laws when they appear? How can educational institutions hope to produce a new generation of young Americans who are unafraid to challenge tyranny and injustice, if those whose job it is to guide them cannot uphold their own moral positions while teaching?

The bottom line is that students must be willing to trust that their professors are taking stands and making statements based on their academic and moral integrity, not on partisanship. More important still, professors must not violate such a trust once it has been established, for in this day in age, perhaps more than ever, young people need help cutting through the bullshit. And nothing cuts through sensationalist headlines, alternative facts and fear mongering quite as sharply, or as swiftly, as the cold, hard facts of academia.

More than anything, this article is meant to start a dialogue and raise awareness on both the side of the guide and the guided. Professors and students must work together in order to establish a political reality based on fact, free from the partisanship, bias and falsehoods that all too often cloud judgement and curve reality.

In order for this to happen, all those involved in institutions of education must be aware of the variety of differences in people’s beliefs and party affiliations, and must be willing to discuss these differences in an academic setting with an open mind. It is my belief and my hope that through such an expression of genuine mutual respect, American universities and high schools can produce a generation of citizens who are smarter and more compassionate than those who came before.