Gerrymandering has been around a long time, but the foul tactic didn’t become popular until 1812. The term “gerrymandering” was coined after Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts enacted a law to redraw the districts to benefit his party, resulting in one of the redrawn districts looking like a salamander.

Gerrymandering has become more widespread and notorious over the centuries, because of districts produced as a result and the criticism it receives for how elections are affected. Now, the Supreme Court faces a decision on Gill v. Whitford—a case that will have a massive impact on gerrymandering in American politics and could influence future elections.

The Court Case in Question

Gill v. Whitford is an extreme example of partisan gerrymandering in Wisconsin, where most representatives and the governor are Republican, meaning they control redistricting in their state. These Republican leaders hired a private law firm to cooperate with staff members to plan, draft and negotiate a new districting plan. Wisconsin Republicans also tested their maps under a variety of conditions including the question “What if the Democrats/Republicans have a good year?” according to their redistricting consultant, Professor Ronald Keith Gaddie, a political science professor at the University of Oklahoma.

All their efforts exceeded expectations because in 2012 the Republican Party received 48.6 percent of the vote and won sixty of the ninety-nine seats in the Wisconsin Assembly. In 2014, they received 52 percent of the vote and won sixty-three of ninety-nine seats.

The Republicans used two gerrymandering techniques: packing and cracking. “Packing” is the act of packing one party’s supporters in one district to win overwhelmingly, and “cracking” is putting supporters of the opposing party in unrealistically shaped districts, so they are unable to secure a majority vote.

The plaintiffs claim these two techniques used by the Wisconsin Republican Party dilute the value of their vote and therefore votes cast are wasted, meaning that the votes cast are either for a losing candidate in cracking or for a winning candidate in an overwhelming majority in packing, thus their vote doesn’t count as much as a Republican vote.

They argue that their vote doesn’t really count because the election results are essentially predetermined and it violates their Fourteenth Amendment rights—equal protection under the law. It virtually squanders their vote as Democrats because it doesn’t count as much as a Republican vote due to the extreme gerrymandering. They also say extreme partisan gerrymandering violates their First Amendment right of free expression because they were discriminated against because of their affiliation with the Democratic Party.

The Efficiency Gap

What the plaintiffs hope to achieve, is to make it harder for districts to crack and pack by enforcing restrictions on extreme-level gerrymandering. These restrictions will force officials to abide by an efficiency gap, which is the number of wasted votes in an election, from both parties, divided by the total number of votes cast. Abiding by an efficiency gap means the lower the number of wasted votes, the better the gerrymandering is in terms of neutrality.

In 2012, the plan adopted by Wisconsin Republicans had an efficiency gap of 13 percent. In 2014, the efficiency gap dropped to 10 percent, which is still a very high number. Hence, the reason the plaintiffs want to use the efficiency gap as a standard for how greatly gerrymandered a state or districts can be.

The Path Through the Courts So Far

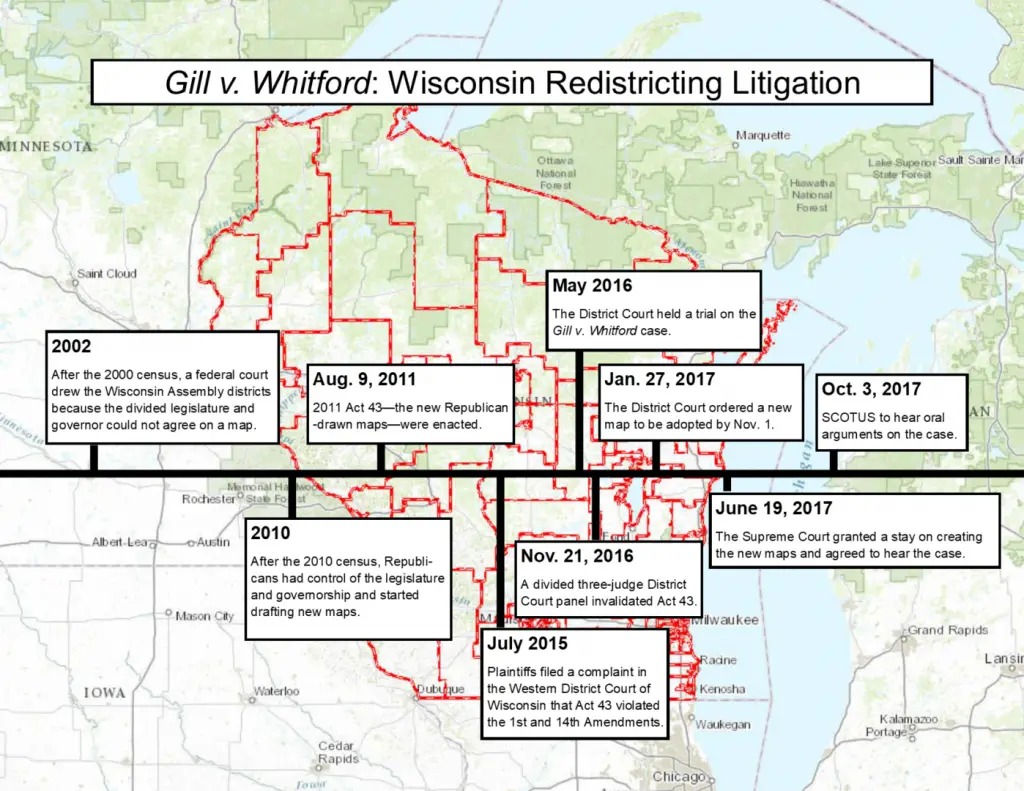

The lawsuits were filed on July 8, 2015 and on April 7, 2017. A panel of three judges allowed the case to go to trial, and the fact that these judges allowed it to go to trial marked the first time in three decades that a partisan gerrymandering case survived a motion to dismiss, which is a request to have a court dismiss a case, usually filed by the defendants.

From there, the trial was held in late May and in November of 2016. The three judges ruled two to one. They determined that Wisconsin redistricting plans were unconstitutional because partisan gerrymandering can’t be justified by the legitimate state concerns and neutral factors such as political topography according to the opinion.

After Wisconsin filed for an appeal asking for the Supreme Court to review the lower court’s decision, the Supreme Court agreed and oral arguments for this case were heard on October 3, 2017.

It probably won’t be until late June that a ruling will be made on Gill v. Whitford, but the central focus is on Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, appointed by President Reagan in 1987 and the court’s swing voter, on how he will vote. Kennedy has sided with moderates in many court cases, such as Lawrence v. Texas (2003), Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) and in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which legalized same-sex marriage nationally.

Impact on American Politics

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Whitford in this case, gerrymandering will still exist. But extreme gerrymandering, where one party is favored to win in almost any circumstance, will be illegal. This will help level the playing field in politics, though not completely. Though, no matter how they are drawn, districts will almost always favor one party over the other. But one party won’t be favored so much that their opposition has almost no chance of winning an election. The efficiency gap won’t be as high as 10 or 13 percent. This may change outcomes of future elections and the majority party in state legislatures drastically, mildly or not at all.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Gill, extreme partisan gerrymandering will continue, and winning districts will remain looking like puzzle pieces. Extreme partisan gerrymandering will also continue to virtually waste votes as the outcomes are predetermined based on the drawing of districts. One party won’t get a majority of the vote but will win most of the seats, whether the party is Republican or Democratic. And, voters will be punished for associating with a certain party because their vote won’t really count based on how a district is drawn. This ruling will also place the responsibility of controlling partisan gerrymandering into the hands of the executive and legislative branches—who will most likely do nothing to curtail extreme partisan gerrymandering—and out of the hands of the courts.

To be completely clear: gerrymandering is not just a Republican problem. Democrats gerrymandered Maryland in order to flip a district from red to blue, ousting incumbent Representative Roscoe Bartlett, with the same tenacity the Republicans had in redistricting Wisconsin. Therefore, whatever decision the Supreme Court comes to will affect both parties and every voter.