The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the xenophobic sentiment against the Asian American community as U.S. President Trump adds fuel to the fire with misleading statements in the press. Not only do we call on our family and friends to wear masks, but we also tell them to stay safe when they leave their homes. There is danger in the form of human beings — people who lash out against Asians and Asian Americans because of their fears.

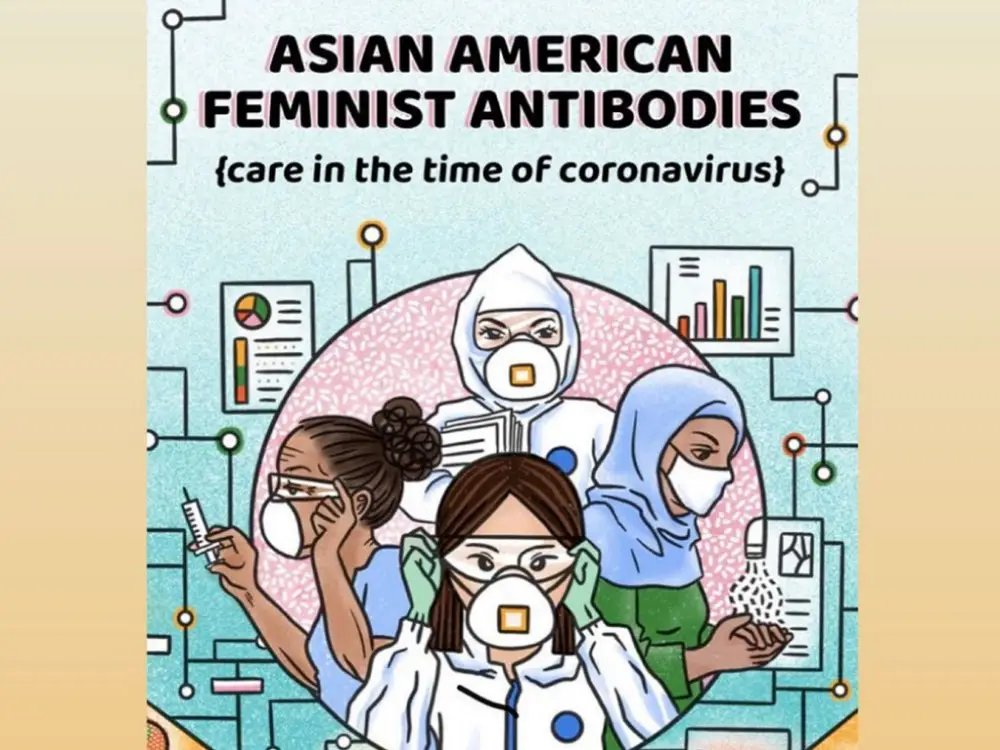

In order to bring the community together through this crisis, the Asian American Feminist Collective released their third magazine, titled “Feminist Antibodies.” The Asian American Feminist Collective is a New York-based nonprofit organization that focuses on intersectional feminism to advocate and provide space for the Asian American community.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-Se_4gAWyV/

At the beginning of March, the group started calling for personal accounts from the community as they began to create the zine. They wanted stories about xenophobia, especially from frontline workers. Through a collective effort, the organization was able to publish “Feminist Antibodies” on March 25.

The title itself emphasizes how people of Asian ethnicity are not the virus, playing with the symbol of racism through the analogy of pathogens. As a society, we need antibodies against the spread of hate and discrimination.

History of Discrimination Against Asian Americans

So, you may already know the rise and fall of the perception of Asian Americans throughout U.S. history. If not, that’s okay.

During the 19th century, Chinese workers came to the U.S. to work on the railroads, facing backlash as foreigners. This led to the Page Act of 1875, which prohibited entry to undesirable immigrants, particularly Chinese women. People feared that they carried diseases that would affect white people.

A virus that’s racially oriented? Sounds familiar? The alienation of Chinese women in the public eye fed into their exoticization. Lotus Blossom. Dragon Lady. They came to seduce the white man.

Then the Yellow Peril hit. Western countries feared the threat posed by Asian countries. It was the “us versus them” mentality as people labeled these countries the Orient — the Other.

The name Yellow Peril holds negative connotations. It highlights the dangers of Asian people by their skin color. In doing so, it cements the idea of white as innocence. Nonwhite skin colors equate to danger.

In “Feminist Antibodies,” activist Amanda Yee writes about how COVID-19 has brought back the ideology of the Yellow Peril. Among the names that the virus has received, CCP virus — as some have taken to calling it — explicitly links it to the Chinese Communist Party.

Is this accidental? No, it’s a political move. Yee says, “Coverage of coronavirus and its consistent framing…as a crisis of CCP legitimacy is not accidental, but deliberate, revealing the U.S.’s thinly veiled anxiety over emerging Chinese economic and political influence, and its own declining hegemony.”

It circles back to the threat posed by an Asian country. In 2016, Donald Trump was elected as the 45th U.S. President with his slogan “Make America Great Again.” His platform centers on racial discrimination, such as deporting undocumented immigrants and building a wall at the Mexican border. Perhaps it’s also a hint of anxiety from the American public, as Yee mentioned.

By keeping people divided through racial stratification, the government and the media enforce the image of the distant enemy — the CCP. The rise and fall of the Asian American image is very much linked with the American political agenda across the Pacific.

Unfortunately, the Asian American community takes the brunt of xenophobia as the “forever foreigners” on domestic soil.

How Xenophobia Affects Asian Americans

Even though it’s easy to discuss ideology in the political sphere, it’s hard to understand such beliefs when one considers the ramifications on individual lives.

How can people hold so much hostility against another group of people? “Feminist Antibodies” dedicates an entire section to personal essays and accounts from people affected by xenophobia in the past and in the present.

From poet to restaurant worker to graduate student, every snippet shows the motif of racism. Each story is a person who has been discriminated against. It’s a representation of what the community has been experiencing.

“A guy on my train started yelling at all the Asians to get out with our ‘egg roll virus’ and ‘samurai virus,’” said Veronica, a Chinese American nonprofit worker.

The current issue of racism reminds me of the French Canadian movie “Ararat,” which was directed by Atom Egoyan. It is a historical retelling of the Armenian genocide that occurred between 1915 and 1918, and it explores the issue of representing history in film and media. It also delves into the erasure of the Armenian people’s history as the Turkish government denies the occurrence of the genocide.

One Armenian character, Edward Saroyan, says, “Young man, do you know what still causes us so much pain? It’s not the people we lost or the land. It’s to know that we could be so hated. Who are these people who could hate us so much? How can they still deny their hatred, and so hate us? Hate us even more.”

Hatred. Hostility. Xenophobia. While there is no justification for these feelings, “Feminist Antibodies” offers solidarity and lists of resources as a way to fight back. It was also made to inform the public of the issue occurring to the Asian American community. Through the magazine, Asian Americans use their voices to speak out.

Because, in the end, we need to take care of ourselves, of each other, of everyone in the community. That’s what we need to do as a nation.