Suzanne Collins deliberately subverts fan expectations in “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes,” her highly anticipated “Hunger Games” prequel, by crafting a seemingly dull narrative as a means to interrogate our enduring cultural obsession with violence in entertainment.

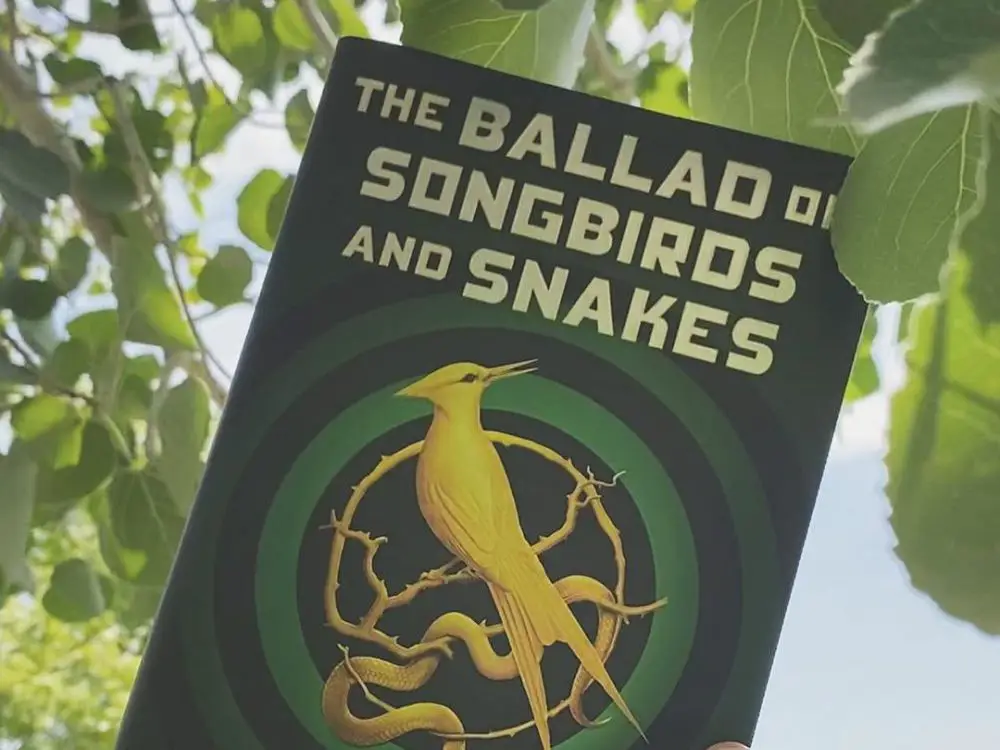

“The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” provides the backstory of villainous President Coriolanus Snow and tells the story of how the titular Games came into existence. When I first picked up the book, I was surprised.

Subverted Expectations

Before the narrative even begins, there is a vast epigraph that boasts how the prequel takes inspiration from a wide range of literary and philosophical sources, including the likes of Hobbes, Wordsworth and Mary Shelley — seemingly more apt for a 19th century tome than a young adult novel.

On the very first page of the book, two revelatory bombshells are dropped on the reader, a pair of major Easter eggs that immediately link the prequel to the original series.

Number one: Coriolanus Snow, the embodiment of the Capitol’s sickening injustice and opulence, was once as “poor as district scum,” resorting to filling his stomach with cabbage soup to mask his poverty from his classmates and teachers at the prestigious academy he attended in the Capitol.

Number two: Snow lived in the crumbling penthouse of a decaying legacy with his cousin, Tigris, the gone-to-seed stylist from “Mockingjay” who helps Katniss and her fellow rebels when they attempt to overthrow Snow and the Capitol.

Yet, what struck me most while reading “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” is that it just didn’t feel like “The Hunger Games.” Where the dystopian series revolutionized the world of young adult literature by interspersing a cutthroat political commentary on consumerism and violence amidst fast-paced action and neat prose, its prequel suffers from laborious pacing, weak characterization and an overwhelmingly florid writing style.

Lack of a Strong Protagonist

The 18-year-old Snow, while facing his share of struggles and moral dilemmas, is simply not as compelling a narrator as Katniss. The story of a girl fighting forces larger than herself that she inevitably must overthrow is a familiar one, yielding a believable and relatable protagonist.

In contrast, Snow is far from being a multidimensional character. For most of the narrative, he is little more than a budding Machiavellian. Snow obsesses over his blond curls and academic achievements, oblivious to the lives of the people surrounding him: the sacrifices a young Tigris has to make to protect him, the plight of his friend Sejanus and a District 2 boy whose father bought his way into the Capitol. He only considers them when he wants to better himself or get something from them, namely money or warm food. Snow is self-involved and superficial, an ostentatious peacock to Katniss’ fiery mockingjay.

“The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” also makes no attempt to garner the reader’s empathy for its protagonist — although, I didn’t find Snow to be an unbearable narrator, as some had feared. In fact, I found his ambition to be somewhat admirable. Still, Snow felt oddly flat and distant. His distance stems from the fact that “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” is narrated in a clinical third-person, unlike the immediately empathetic first-person narration in “The Hunger Games” series.

In the prequel, instead of being thrust into the arena by a cruel Capitol with Katniss Everdeen, we become spectators of the Hunger Games, watching while children are forced to fight each other to the death in a rudimentary death match. Perhaps, in looking over the shoulder of mentor Snow, we are even more complicit, actively helping the Games run smoothly. This leads me to discuss the most unexpected (and disappointing) aspect of “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes”: the Games themselves.

The Games

Set 64 years before the events of “The Hunger Games,” “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” depicts the 10th annual Hunger Games, in which a brand new setup for the event is introduced — students at the elite academy are chosen to mentor the district tributes.

Unsurprisingly, Snow’s puffed-up pride is hurt by being assigned the “lowest of the low,” the female tribute from District 12: Lucy Gray Baird. She immediately stands out from her fellow tributes; she has a way with snakes, wears a rainbow dress and often breaks into song.

Although this differs from the original series, where previous victors act as mentors to the tributes, it is understandable, considering the Games are so early in their creation in the prequel. Nevertheless, much like the sadistic Capitol citizens, I was still excitedly anticipating how the Games would take shape, comparing them to those of the original trilogy.

Would the tributes be transported to the Capitol in a high-speed train, pampered with luxury clothing and food before their slaughter? What would the arena look like? Which extreme climate would it take place in? What would the costumes in the Tribute Parade be like?

But alas, in “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes,” the Capitol has not yet become a center of wasteful decadence, as it is fresh from the destruction of the First Rebellion. The Games take place in a crumbling arena of indeterminable size, once used for military parades, and further damaged by an unsuspected bomb attack — more akin to the Roman gladiator games that inspired Collins than the futuristic environment seen in the original trilogy. The tributes are treated like animals, transported to the Capitol via cattle car, kept behind bars in what is essentially incarceration and seen to by a veterinarian for their injuries.

Instead of a glamorous Tribute Parade, they are displayed in a cage and denied food and drink; some of them even die before the Games begin. The Games also lack the bloodthirsty audience from “The Hunger Games.” Most of the Capitol citizens can’t bring themselves to stomach the brutality of it, and those in the districts don’t have access to television.

Dull Characters

At best, the Hunger Games in “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” echo the drab delights of a circus performance. At worst, they are simply dull. The tributes, apart from the colorful Lucy Gray Baird, are unwilling to work with their mentors and remain silent during the interviews. They are essentially indistinguishable from one another.

Likewise, their mentors, students of the Capitol’s Academy, are equally one-dimensional. With their ludicrous Capitol names (Lysistrata Vickers, Florence Friend and Domitia Whimsiwhick, to name a few), they border on caricatures at times, more akin to the copy-and-paste Sugar Rush racers from Disney’s “Wreck-It Ralph” than meaningful characters. The characters simply feel lacking in contrast to their skillfully written and fully formed “Hunger Games” counterparts. The sheer number of them (one mentor for each of the 24 tributes) leaves no room for adequate characterization.

The drab characterization of “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” notwithstanding, many criticized the prequel for being “boring,” with the Games themselves being unexpectedly anticlimactic. I also was initially disappointed with how they turned out, finding them to be dull and flat.

Intentional Monotony?

Then, after digging deeper into reviews of the book, I started to wonder whether the monotony of the Games was intentional on the part of Collins. After all, as the Games only fill around 100 pages of the staggering 517-page narrative, perhaps Collins made them purposefully insignificant and unentertaining for the reader to make them question their own expectations surrounding entertainment and violence. What did we expect from the Games? Gory deaths narrated in full detail, with some added emotional impact, as it was in “The Hunger Games”?

Well, there certainly were a few violent deaths depicted in “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes.” So, what made these Games dull? Nothing happens — the tributes aren’t always actively killing each other. Most die of indirect causes, such as rabies or ingestion of rat poison.

If this was Collins’ intention for her book, then she succeeded. My readerly expectations of “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” were entirely overturned. For those who want a more exciting Hunger Games, like the gory battles of fan favorites Johanna, Finnick or Haymitch, I implore you to consider: Why do you want to see such violence depicted as a source of entertainment?

In the end, is there a meaningful difference between those in the Capitol who watch children murder each other for entertainment and those in our capitalist society who read young adult novels about it? The boundaries become especially blurred in the current time of consumerism, but the key distinction is education versus entertainment. Reading about the dystopian horrors of an imagined future can potentially lead us to reflect on our own societal issues.

Upon my first reading of the novel, I was deeply disappointed as a fan of “The Hunger Games.” It diverged from the original trilogy, its characters were flat and most of all, its Hunger Games were unexpectedly dull; however, a deeper delve into the philosophical backdrop of “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” proved the novel’s apparent dullness is its greatest strength.