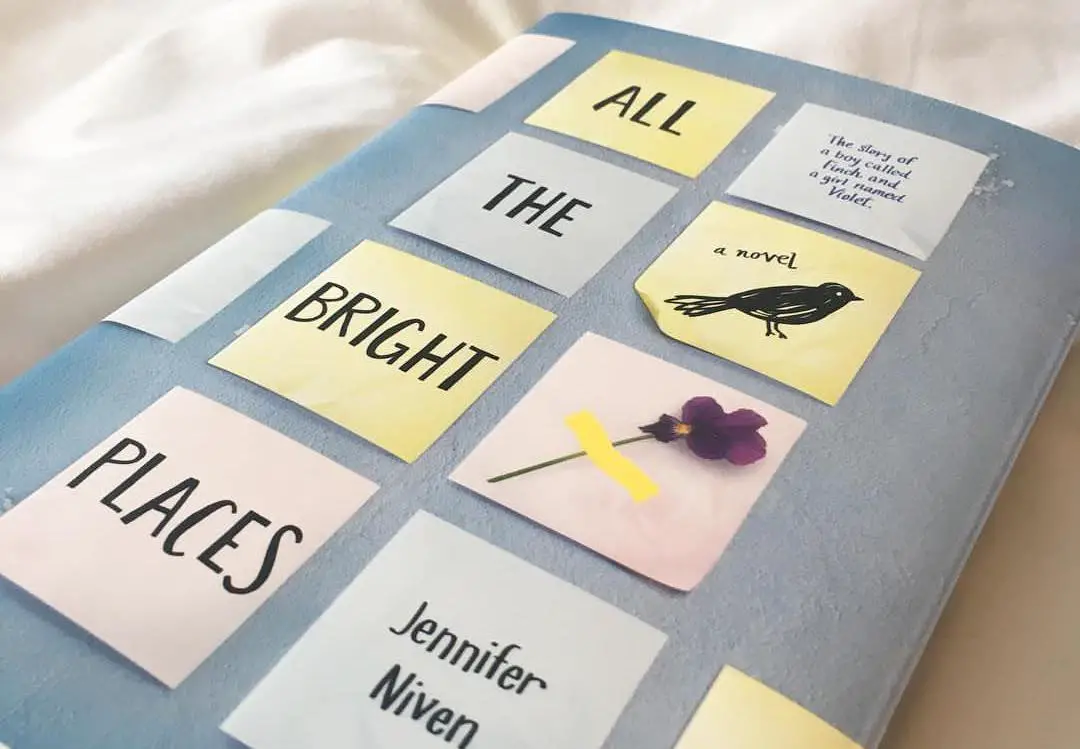

On Jan. 6, 2015, Jennifer Niven took a leap of faith and published her now New York Times’ best-selling novel, titled “All the Bright Places.” Her novel rapidly gained traction amongst teens and young adults, and it soon became a story that many hold deep in their hearts and still to this day continue to cherish.

Understandably, “All The Bright Places” has become a monument of vital significance to many of its readers, partly because of the relatability of the two main characters, Theodore Finch and Violet Markey; however, its reputation and elevated status can be attributed to its theme of mental illness.

Mental illness is difficult to accurately portray. Many writers lack the understanding of how holistically painful and arduous it can be to battle mental illness, and the result is a tendency to romanticize it and use it as a personality quirk. And because many contemporary young adult (YA) novels revolve almost entirely around romantic elements, mental illness acts as an idiosyncratic emblem to set said character apart from the rest of the crowd, thus making them more “attractive” to their romantic interest.

In some cases, novels will even whittle down characterization to this singular trait, communicating the idea that an individual who is struggling mentally is nothing more than their mental illness.

With so many of these flawed literary portrayals out in the market, “All the Bright Places” is most accurately described as a breath of fresh air to many of its readers who resonate with the struggle of living with mental illness.

Suffering deep loss and enduring several loved ones’ suicides, Niven is pragmatic in her approach to mental health through “All the Bright Places.” She does not sugarcoat mental health as something that elicits romance. The story she offers to the world is tragic and traumatic, leaving readers sore in the reality of what our minds can do to us, but also artfully and accurately bringing awareness to the tribulations accompanying mental illness.

Both Theodore Finch and Violet Markey suffered tremendous loss in some form and, consequently, battle with depression. A project on the landmarks of their hometown in Indiana forces the two together, and they find themselves slowly enamored with one another, despite the initial sentiment of loathing on Violet’s part.

As Violet’s relationship with Finch seemingly aids in her emotional recovery, allowing her to see the world in color once more, Finch is undeniably falling into a grayscale world in which he cannot even seek salvation through his fervent feelings for Violet.

Finch and Violet’s relationship is real. Sad and unfortunate, of course, but real nonetheless. Mental illness is not a channel that authors can manipulate in order to ignite romance. The ugly truth is love, or a romantic partner, is not the universal solution to relinquishing mental illness, as is the case for Theodore Finch. What readers take from the novel is a lesson in the true adversity following mental illness, rather than the oversimplified notion that countless other YA novels unknowingly teach their readers.

“All the Bright Places” was truly a milestone in discussions of mental health within the contemporary fiction literary community and has garnered quite the devout following. Many readers have gone as far as to tattoo quotes and symbols in remembrance of feeling intimately understood.

Earlier this year, Netflix started production on a film adaptation of “All the Bright Places,” starring young talents Justice Smith (of “Detective Pikachu,” “Jurassic World” and “Paper Towns”) as Theodore Finch and Elle Fanning (of “Maleficent,” “Super 8” and “20th Century Women”) as Violet Markey. The film is set to come out later this year.

Can we talk about this Elle and Justice reunion? #ElleFanning #JusticeSmith #AllTheBrightPlaces #Finch #Violet pic.twitter.com/yR3ScLZFdQ

— All The Bright Places (@AllBrightPlaces) May 10, 2019

Niven has become known for her interaction with fans through social media, especially in providing updates for the process and progress of the film. She is seemingly thoroughly involved in the production of the film, leading fans to assume that the cinematic adaptation will remain substantially faithful to the tone and themes of the novel.

Given the ardent following of the novel, Niven — and all those working on the film — are under immense pressure to stay true to the essence of the book that caused people to fall in love with it in the first place. The main concern following the adaptation of “All the Bright Places” is whether or not it will handle mental health with identical sensitivity as in the book, or if it will adopt an air of romance as a means of appealing to a wider audience.

It might be safe to assume that the film adaptation will stay true to the heart of the novel, as Niven is an ardent advocate for mental health awareness, working constantly to provide resources to her followers in need of emotional support. It is doubtful she would allow the novel to be misrepresented or stray from an issue she holds so dear. Readers can trust Niven will do everything in her power to produce a film integral to the conversation of mental health and a story of a fulfilling, yet real, love.

Endearing yet genuine, “All the Bright Places” tastefully conveys emotional intimacy holds a certain pricelessness but cannot always ensure refuge — and often does not. Violet made Finch feel, but she could never have expected to be an anecdote to the agony plaguing his mind. Nevertheless, Finch appreciated the experience of escape and support through Violet, a vital resource to those in pain.

In the poetic words of the eccentric Theodore Finch: “You make me lovely. And it’s so lovely to be lovely to the one I love.”

Be an oasis. That simple devotion might be all one needs to feel lovely.