Although I usually avoid promoting culinary trends to college students, there’s a strong case to be made for foraging.

Hunter-gatherer jokes aside, the ability to identify local plants and the desire to serve them has become commonplace within the gastronomic community. Chefs describe foraging as eating hyper-locally, an intensification of the “eat local” movement. It means utilizing not just what grows in your state, but what grow in your backyard. The result: fresher foods with a stronger sense of place.

Fernando Arias is a chef at qui in Austin, a nationally renowned restaurant that emphasizes locally grown and foraged ingredients in its cuisine. Restaurants cooking at the highest level refuse to use anything less than the best products available, as they know that compromising on the components of a dish lowers its potential. “As far as cooking with local foods,” says Arias, “they’re just a much, much higher quality than imported ingredients.”

Given the same product—one grown locally and one imported—chefs will almost always choose the local ingredient. “If you have a tomato that someone grew in Austin,” explains Arias, “it’s just always going to be fresher than one imported from Florida. You don’t have to transport it, which means you get it days sooner.” In the culinary world, days make all the difference.

As a result, some of the best restaurants in the world routinely forage for their ingredients. They get fresher product, yes, but it’s more than that. Chefs go through the extra effort because foraged products differ from locally grown products in that they thrive naturally in an area, giving them a geographic idiosyncrasy. The appropriate term for this phenomenon is terroir, a word that describes the complex relationship between place and taste. Unfortunately, most chefs lack the required time or knowledge needed to forage their own ingredients.

So, they turn to farmers.

Dorsey Barger is an urban-farmer in Austin and co-proprietor of HausBar Farms, a sustainable urban farm that offers vacation rental space, day camps and workshops. She supplies many high-end restaurants in Austin with vegetables and lesser-known edibles.

“The problem is,” says Barger, “there’s going to come a day when the factory farming system can longer sustain itself.

“If we don’t have people who are educated about what we can eat around us, then as a society we’re in a lot of trouble.” Barger quickly distances herself from doomsday types, acknowledging that any monumental shift in agriculture will likely take place a century from now.

To her though, that makes the knowledge even more important. “This education about what is edible around us needs to be preserved,” she says, unaware of her pun. “We need to be able to reteach ourselves how to eat from things that want to grow.” Cultivating lesser-known, naturally occurring edibles is more than apocalypse insurance for Dorsey: she takes a huge enjoyment in growing plants that most people have forgotten they can eat.

Unsurprisingly, restaurants love her. A chef having exclusive product to cook with is like an artist having exclusive colors to paint with, and qui uses Barger like their secret weapon. Every week she brings in leaves, plants and flowers that no one in the city gets but them. “We basically buy everything she brings in regardless of what it is,” says Arias.

Dorsey’s produce makes it onto some of the most revered tasting menus in the country, partially based solely on the rarity of the product. “Right now she’s bringing in okra flowers,” Arias says. “There’s really no reason for anyone to sell [them] because you pretty much have to lose the okra to get it. But Dorsey thinks they’re cool.”

These exotic ingredients provide chefs with more options, upping the ceiling of each dish. “The sauté cook fried [an okra flower] the other day and it was amazing—like tempura on the outside but gooey on the inside like okra,” Arias says. And while okra grows throughout the south, a lot of Dorsey’s product is indigenous to the central Texas area. That means the restaurants that use her edibles are some of the only places in the country to eat it.

Working with Barger has introduced Arias and other chefs to an entire world of local edibles, many of which grow wild throughout the city. “I’ll be cooking for my girlfriend and go outside,” says Arias, “and I’ll see some oxalis. Maybe it’s not a huge part of the dish but I’ll rinse it off and put it in a salad. It’s got a crazy lemon flavor that’s amazing.”

Arias underscores the central irony of foraging: many of the ingredients on qui’s $120 tasting menu grow in parking lots throughout Texas.

“I mean it’s kind of silly that we have to pay for them obviously,” says Arias, “but we do such big volume that I don’t have the time to pick a pound of henbit.” It’s not just qui and it’s not just Texas: people across the world are paying top dollar to eat plants that grow in their front yard.

Purslane grows in the cracks of the sidewalk in front of the UT Co-op and Turk’s Caps surround a UTSA parking garage. Sorrel grows along the banks of the San Marcos River and gardeners mix oxalis in with bedding plants at Texas Tech. College campuses are teeming with edible plants so delicious that the best restaurants in the country pay top dollar for them—you just have to know what they look like. As Arias says, “You can eat the world around you.”

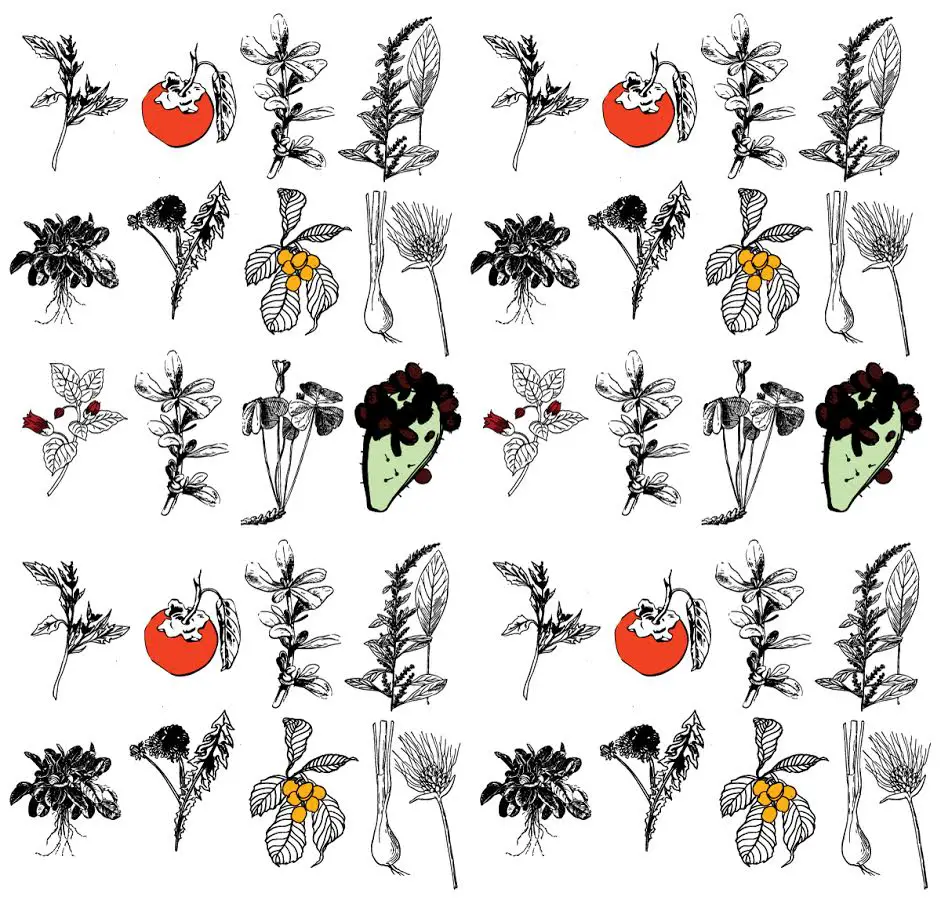

In that spirit, Study Breaks has created a field guide of forageable plants that grow on college campuses in Texas. These carefully curated edibles are an assortment of shoots, fruits and leaves that satisfy the holy trinity of foraging: they’re wild, tasty and very convenient.

The guide focuses on convenience, as no lazier demographic exists than the 18-23-year-old college student. The sloth of this age group is legendary, especially when it comes to cooking. Many college students would skip a meal rather than cook one, and I have witnessed my friends ordering Jimmy Johns while Jimmy Johns sits in their fridge. Trust me, I realize that people who eat uncooked ramen to save two minutes of cooking time are unlikely to wander the woods searching for begonia petals.

But that’s the beauty of foraging: if done right, it’s the easiest way to feed yourself. It requires no grocery shopping and no cooking. You’ve most likely passed past dozens of edible plants as you walk to class. The only thing preventing you from delicious free food is the inability to identify it.

The Study Breaks Field Guide for On-Campus Edibles will eliminate that problem, making feeding yourself as easy as plucking persimmons off the tree near the San Jacinto parking garage. You can eat Turks Cap at crosswalks, loquats in hot tubs, Lambs Quarters at ACL and green garlic at the north entrance of Texas State Tubes. It’s all delicious and all completely free.

Just make sure to double-check what you grab and wash it before you eat it.

Sorrel

On a bachelor party canoe trip down the San Marcos River, the canoe containing all our food capsized several times and waterlogged our supplies. When we finally stopped for the night, the only thing that survived was the alcohol.

Luckily, sorrel dotted the tiny island where we camped. All night we dined on the bright, lemony plant and drank, which might explain the euphoric feeling I associate with eating it. The leafy green looks like spinach and is edible raw. It can be cooked but becomes a nasty brown color when exposed to heat, so aim for raw or light preparation.

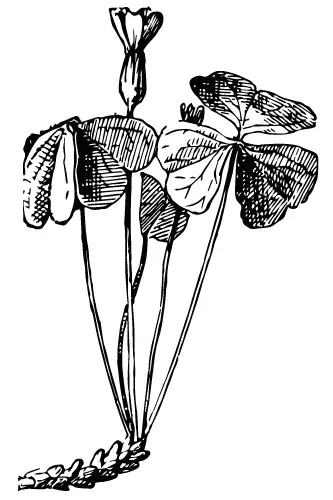

Wood sorrel/oxalis

Referred to in the culinary world as oxalis, the tiny clover-resembling leaf has trifoliate leaves, each of which is heart-shaped and adorable, and is often used as a bedding plant as result.

So if you’re looking at a flowerbed and see cute three-leafed plants, you’re most likely looking at oxalis. Cooks often use oxalis to garnish dishes because of its petite figure and tart, lemony flavor, so go ahead and pluck some to garnish your Cabana Bowl.

Purslane

Often considered a weed, this succulent hugs the ground like a delicious net. Purslane is also incredibly nutritious, containing more omega-3 fatty acids than any other leafy vegetable, in addition to a high concentration of Vitamins A and C.

More importantly, it’s delicious and can be eaten raw, stir fried or lightly cooked. It makes a wonderful base for a salad because the entire plant is edible, including the stalk and leaves. Purslane is tender but firm and has a refreshing snap when broken.

Restaurants throughout the country feature purslane during its growing season, and you can find it at local farmer’s markets and in parking lots.

Turk’s Cap

These beautiful bell-shaped flowers are perhaps the most proliferate edible on this list: a trained eye can find Turk’s Cap bushes nearly anywhere in the state.

Simply pluck the tiny red flower off the stem, pull out the stamen, remove the petals from their base and eat them. In the spring, Turk’s Cap petals taste incredibly sweet, and in Mexico the flowers are called manzilla.

Their sweetness mollifies as the heat increases but they’re worth eating any time you spot one. Barger brings plastic bags filled with hundreds of Turk’s Cap to restaurants throughout Austin, leaving unlucky prep cooks to painstakingly deflower the tiny petals.

Lambs Quarters

Barger thinks that these green weeds are the most underrated wild edible in the state. “Lambs Quarters are the only leafy green plant that grows in Texas during the heat,” she says. “If you’re trying to eat locally during the summer, these are your only option for leafy greens. Kale, chard and spinach don’t grow well in the heat.”

Lambs Quarters’ leaves always look dusty due to a white coating but they’re fine to eat raw. Although sturdier than spinach, they can be cooked in many of the same ways: Barger suggests a simple sauté with garlic and salt. The smallest leaves on the stalk are the most tender and make for a perfect addition to a salad.

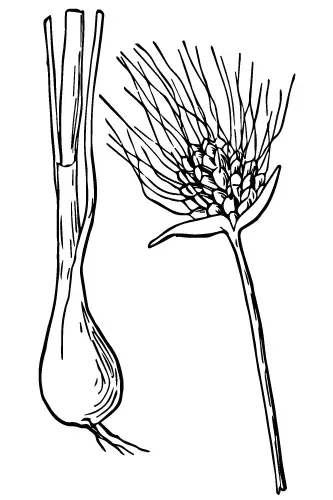

Wild Garlic

Wild garlic and wild onions are easily confused, but the good news is that it doesn’t really make a difference. The best way to tell is their stalk: round and hollow means wild garlic; flat and broad means wild onion.

Either way, if the plant you pull up has a white bulb and smells oniony then you can eat it—and should! Pull them out of the ground and chew on the garlicky stalk if you’re looking to stay single, or barbecue or grill them whole with olive oil and salt.

Dandelion greens

Dandelion greens are the plant version of the ugly but intelligent sibling that everyone ignores. Every human on Earth is familiar with the innocent joy of blowing dandelion seeds into the air, but very few have taken the time to get to know the greens behind the flower.

Dandelion greens are one of the most nutritious greens available, boasting a full DV of Vitamins K and A, in addition to fiber, iron, calcium and a million other things. They are, if we’re being completely honest, a little bitter (as they should be, considering their sibling’s popularity!).

Bitterness means a high presence of antioxidants and vitamins, but that’s irrelevant if the plant tastes terrible. Fortunately, a quick sauté or blanch will leach the unpleasant taste and still retain most of the health benefits. Cutting the greens into small portions and mixing them in with salad also works well if you’re looking to eat them raw. Any way you slice it, dandelion greens are everywhere and they’re incredibly healthy.

Prickly Pear Fruit

Harvesting prickly pear fruit is the most dangerous task on the list, but it’s also the only one that leads to alcohol—a classic pairing. The only thing standing between you and homemade prickly pear margaritas are tiny, fiberglass-like needles on the mahogany cactus fruit.

Most experts suggest using tongs to remove and handle the fruit, but anything that prevents your skin from touching the bulbs will work. Using tongs or gloves to handle the fruit, cut off the tips and then cut away the hard casing to reveal the sweet treasure within.

Puree and strain the fruit to create prickly pear juice. If you want margaritas, use some of the juice to make a prickly pear simple syrup, and then go ahead and die because that’s the best thing you’ll ever taste in your life.

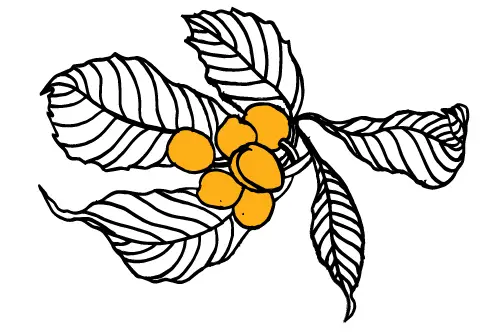

Loquats

Loquats were the first foraged fruit I ever ate. At the time I had no idea what they were or whether they were safe, but it was fruit hanging from a tree in my friend’s backyard and I was ten.

These delicious, sour fruits grow all throughout Texas in the spring. They are delicious when picked straight from the tree and are truly the people’s fruit.

Amaranth

Legend has it that amaranth was so important to the Aztecs that when Cortes arrived he destroyed all the granaries storing its seeds and declared growing it a crime. As a result, the delicious leaf nearly disappeared as a food source.

Luckily the hardy plant grows voraciously anywhere it can, and chances are you’ve seen it growing through a crack in the sidewalk. The beautiful plant has dozens of variations, but one red-hued species is particularly well received in the culinary community for its vibrant coloring and peppery taste.

Persimmons

Despite the fact that persimmons are native to Texas, the most commonly consumed variety is the Fuyu, a Japanese species. One tree near the San Jacinto garage on the UT campus bears these beautiful real-life emojis.

They are light orange with tiny stems that must be removed before eating, and must be eaten only when they are incredibly ripe. Otherwise the fruit’s high level of tannins produces an unpleasant mouthfeel. I recommend peeling away the skin although it’s not necessary: simply slice and enjoy, taking care to avoid biting the seeds.