Sexual orientation (who a person likes) is free-flowing and should be viewed on a spectrum. Though spectrums can be complex, as there are an infinite number of possibilities, what’s most important is ensuring a person understands they belong wherever they feel most comfortable.

Important to note: Referring back to the fluidity of sexual orientation, a person’s position on the sexuality spectrum can change at any time—nothing is permanent, and there’s nothing wrong with moving positions, identifying differently or choosing not to use labels as a result. You’re never stuck in one spot on the sexual orientation spectrum, because you get to decide where you fit best.

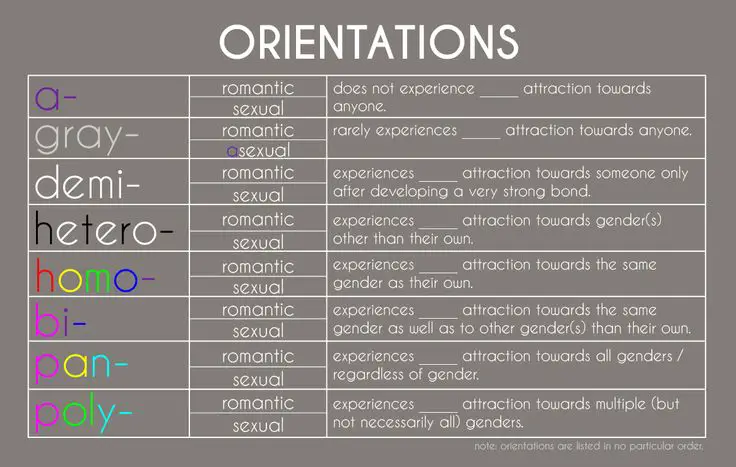

There are a multitude of spectrums, including but not limited to gender identity, gender expression and biological sex. Looking specifically at sexual orientation and attraction, heterosexuality may fall on the far left and homosexuality on the far right, acting as two opposite points. Pansexuality, bisexuality and asexuality tend to fall somewhere in the middle.

Asexuality is an umbrella term and exists on a spectrum of its own. Contrary to popular belief, love doesn’t have to equal sex. An asexual person, also referred to as an “ace,” may have little interest in having sex, though most aces desire emotionally intimate relationships.

A person doesn’t identify as asexual because they fear intimacy. Aces aren’t people who choose abstinence due to unhealthy relationships, support sexual repression due to dysfunction or identify with asexuality because they’re unable to find partners. Celibacy is a choice, while asexuality is a sexual orientation.

Instead, an asexual person wants friendship, understanding and empathy. Aces may experience arousal and orgasm — although an asexual relationship is not built on sexual attraction, aces may choose to engage in sexual activity (but some aces are not at all interested in sex). Within the ace community there are many ways for people to identify, demisexual and graysexual included.

A graysexual person may also be referred to as gray-asexual, gray-ace or gray-a. Referring back to the asexuality spectrum, sexual (someone who does experience sexual attraction) may fall on the far left, and asexual (someone who doesn’t experience sexual attraction) on the far right—acting as opposite points. Graysexuality tends to fall somewhere in the middle.

Graysexuality refers to the “gray” area between sexual and asexual, as sexuality is not black and white. A gray-a person may experience sexual attraction occasionally, confusingly and rarely, under specific circumstances. Essentially, graysexuality helps to describe people who don’t want sex often, but do sometimes experience sexual attraction or desire. Graysexuality connects with the fluidity of sexual orientation—gray-ace people don’t fit cleanly into the “I’m sexual,” or “I’m asexual” molds.

Important to note: Although graysexuality can be confusing, gray-a people may cling to the label because existing without one can be alienating. Having a space for people who don’t clearly fit certain labels like “asexual” is important—gray-ace identities matter, their experiences (although complicated) are real and their feelings are valid. There are people who don’t attach labels to themselves, but having them is crucial for people who need them.

Graysexuality is not a new term; there’s an article on www.thefrisky.com from 2011 entitled, “What It Means To Be “Gray-Sexual.”” The article highlights two women (Belinda and Elizabeth) who identify as gray-ace. Belinda said in the article, “There’s no reason why I should bend over backwards sexually to do something I don’t want just because I should want it or because everyone else wants it.” Referring back to the importance of the term “graysexuality,” people should know there’s nothing wrong with not having sex. Asexual people are not “broken,” but they exist without feeling sexual attraction.

Demisexuality is another term on the asexuality spectrum. A demisexual person only experiences sexual attraction when they are deeply connected to or share an emotional bond with another person. Even then, they may have little to no interest in engaging in sexual activity.

Demisexuality is often misunderstood. Although most people want to get to know someone before having sex with them, feeling sexually attracted to someone is much different than having sex with them.

Sexual attraction is uncontrollable: you either have sexual feelings or you don’t, but engaging in sexual activity is a person’s choice.

A person who’s not demisexual (or doesn’t find themselves on the asexual spectrum) may have sexual feelings for people they find attractive—classmates, coworkers or celebrities for example. A demi-ace person doesn’t initially feel sexually attracted to anyone—they need to feel emotionally connected, and again, may still choose not to engage in sexual activity.

There’s an extreme lack of academic sources detailing asexual experiences, which directly correlates with the lack of asexual representation in scientific studies. Also, when asexual studies are conducted, the study participants need to be diverse—asexual people can be of any gender or age, etc. Knowing more about asexuality from a scientific perspective is important, which is why asexual research and diversity is necessary.

In addition to scientific studies, there’s a lack of asexual representation in mass media—newspapers, magazines, radio, television and the Internet. People rely heavily on mass media to provide them with information regarding political/social issues and entertainment, and yet movies ignore asexuality or promote harmful stereotypes.

For example, “The Olivia Experiment” is a 2012 film focusing on a 27-year old graduate student who suspects she may be asexual. Within the film, however, asexuality is presented as a temporary condition rather than a sexual orientation—Olivia’s asexuality is something she can “fix” if she just has sex. Like previously stated, sexual attraction and sexual activity are different because one isn’t controllable (sexual attraction) while the other is a choice (sexual activity). Also, “The Olivia Experiment” could have highlighted a friendship most asexual people desire, and yet the film desperately failed to do so.

Asexual representation in mainstream media is imperative because aces, gray-aces and demi-aces need to know not being sexually attracted to another person is okay. Asexuality should not be undermined, and not experiencing sexual attraction doesn’t make anyone who most identifies with the asexual spectrum boring.

Note: Asexual Awareness Week is from Sunday, October 23 until Saturday, October 29, 2016.

[…] Getting Familiar with the Sexual Spectrum, Bri Griffith of Carlow University, explains that while someone who is not on the asexual spectrum […]

[…] грейсексуальностьEverything You Need To Know About Asexuality And Graysexuality (так называемый серый спектр) описывает людей, […]

[…] грейсексуальностьEverything You Need To Know About Asexuality And Graysexuality (так называемый серый спектр) описывает людей, […]

[…] грейсексуальностьEverything You Need To Know About Asexuality And Graysexuality (так называемый серый спектр) описывает людей, […]

[…] грейсексуальность Everything You Need To Know About Asexuality And Graysexuality (так называемый серый спектр) описывает людей, […]

[…] грейсексуальность Everything You Need To Know About Asexuality And Graysexuality (так называемый серый спектр) описывает людей, […]