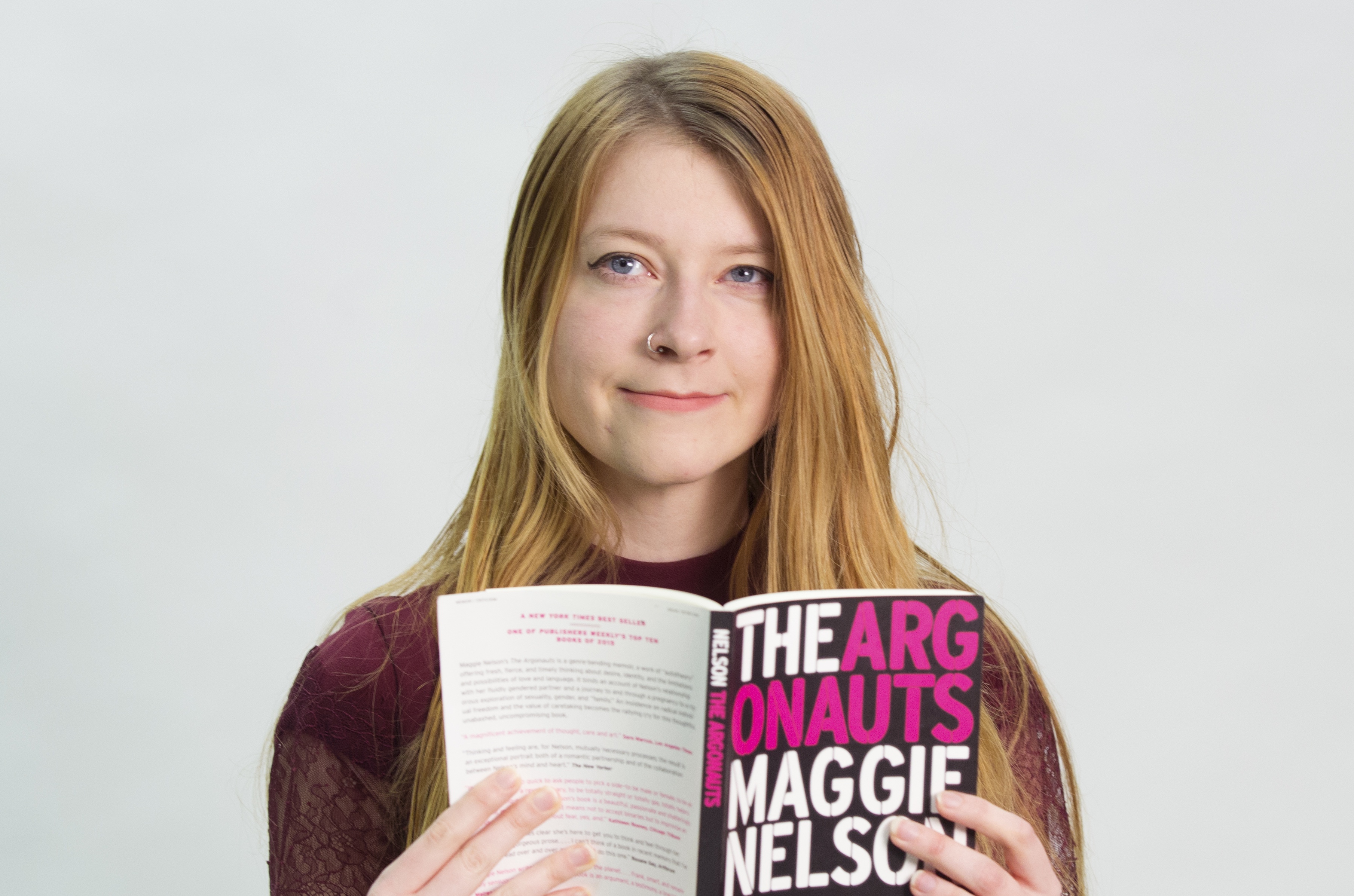

Sarah Hovet is an award-winning poet who has been a member of the UO Slam Poetry team for her freshman and junior years. Currently attending the University of Oregon as a senior, she won the Eleanor B. North Poetry Award for her poem “Edges” in 2017.

While Hovet is a normal college student who runs into writer’s block from time to time, she has already published her work outside of her campus community. Her passion stems from finding inspiration from her studies, surroundings and other poets. Even though the poet is happy with what she has accomplished so far, she wants to continue moving forward in her creative work for the future.

Emily Craig: What did it feel like to win the Eleanor B. North Poetry Award and when did you receive it?

Sarah Hovet: Winning the Eleanor B. North Poetry award feels fantastic. I sent in my poem to The Rectangle, a publication by the Sigma Tau Delta International English Honor Society (STDIEHS), in April 2017. I remember opening my email during the STDIEHS fall 2017 board meeting while attending as a regional representative from the far western region and feeling blown away.

Receiving a poetry award in September is an honor and a $500 dollar prize. It feels fantastic since people tend to tell me and joke (when I say I am an English major and an inspiring poet) that no money comes from either of these job fields. It feels good to know my work has value to others.

EC: Where do you find inspiration for your poetry?

SH: I find inspiration primarily from reading other poets. I think that’s essential to anyone’s poetic practice. I am currently reading a couple of different collections, including “Bright Dead Things” by Ada Limón and “She Had Some Horses” by Joy Harjo.

I’m often inspired by anything that has to do with botany or animals and nature. I like to read a lot of articles about those things, and then often I’ll keep those tabs open on my laptop or my phone until I can put them in my notebook and jot down some notes.

EC: Tell me about your slam poetry experience from the time someone mistook you for the hypnotist?

SH: That article was a companion piece to the University of Oregon commercial that featured a variety of students from all different disciplines and faculty as well, including myself. The author of the article wanted to see a reading of one of my poems, which happened to be the same time as Welcome of Week.

The Welcome of Week organizers put the Slam Poetry Showcase before a hypnotist. It was in the Student Union, and I was there nervously preparing to perform, pulling up my poems on my phone and making sure I knew where the mic was and that my hair looked okay. Someone came up to me and said, ‘Oh, are you the hypnotist?’ And I said, ‘Oh no, I’m a poet.’ That was a little fun performance where I read a full-length poem and full haikus.

EC: What is your preferred style of poetry and what do you tend to write your poems in?

SH: I prefer to write in freestyle or free verse poetry style because I like to put a pen to a page, and with line breaks, usually I know when I want to place them. I like to play around with other styles as well: Shakespearean sonnets, those are fun.

I’m pretty good at getting the syllable count, rhyme scheme and most of the conventions down — I struggle a little with fitting into iambic pentameter, but I just treat this style as an experiment, so I don’t stress out about that while I am writing. Another one I like is pantoum, which is where you have any number of quatrains and the goal while repeating these quatrains is that they take on a new meaning the second time, which is fun. I use those mostly in nature poems because of the cyclical nature.

Also, I like to look through books of poetry and let the styles amaze me, which reminds me of my favorite quote about poetry: ‘Writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down.’ — Robert Frost

EC: Your poem “Grind,” was that an actual dream, and if so, how did you process those images in your head into a poem?

SH: My poem, “Grind,” deals with the theme of anxiety using imagery from an actual dream of mine where my teeth are falling out. Some of the images in the poem aren’t from the dream because I really want to reinforce my point about the troubles about living with anxiety; the closing image is within the dream world when I look into the mirror and see my teeth growing back. Yes, anxiety grinds me down, but it is also a process of resilience; and what anxiety grinds away always grows back.

EC: How did you start writing poetry?

SH: My emphasis within my creative writing minor is actually fiction because growing up throughout my childhood I wanted to be a writer. I wrote a little bit of poetry, but I didn’t think of myself as a poet. Except now that I look back over my notebooks, I actually have more poems than I thought.

Back in eighth grade, I was often inspired by music but had no musical talent and played with the idea of being a music journalist. I look through my old notebooks and still remember which song the poem came about from, whether the musician was the Pixies, David Bowie or any alternative rock band. Early on, my inspiration came from musicians who double as poets, such as Patti Smith.

I have always been producing poetry even if I thought of the writing as a side project, but my transition from high school to college is really when my earnest writing in poetry began my main medium over fiction. During my Freshman Orientation, I became a member of the University of Oregon Poetry Slam team. This was really the period in my life when it became something I associate myself with.

I have a word document of over 100 pages of poems from freshman year until now. Starting college, I was looking forward to being on campus, and wanting to change my life, and poetry was the way to do that.

EC: What is your writing process like?

SH: I carry a little journal with me wherever I go, so I try to pull it out so I can immediately write down everything that’s in my mind. I don’t want to lose anything. Sometimes it’ll happen in class; I just scribble in my class notebook and transfer it to my journal during a break. When I’m doing that essential writing, I often know where I want to put the line breaks and have some word choice in mind, but I don’t I think much more in fragments. Then, instead of trying to put it into a structure, I do a little word bank and list out all the fragments that are in my mind and then go through them and kind of build a structure around them.

Sometimes ideas just come to me with a velocity and I write them down in what their ultimate presentation on the page might look like and then sometimes the process is much more a disjointing process. I make decisions about ordering those fragments, combining them or leaving some of them out. Then when I have whatever I intend to put on the page written, I look at the words.

I can usually tell if I have an entire poem here or if this is more of an introduction to a poem and I need to do some deep thinking about where I want to take the poem from now. In other cases, this is more of just an anecdote and I need to break it down as thoughts for two other poems. If I feel like what is on the page is essential, I go on to writing something else or editing old work because I need to let the new work breathe for a little while and then I come back to it with more clarity later.

EC: What helps your writer’s block when you run into it?

SH: During my day I write notes about what is going on or what I learn in class. The action of writing and remembering sparks ideas. I read through ideas in my journal that can become a poem. I flip through poetry books and inspire myself.

Since my poems are about nature, sometimes nature walks help inspire me. Sometimes my class notes can be translated into a poem. Other times, ideas of a poems are in a one-word-or-sentence inspiration list.

I remind myself that the experience I feel when writing the poem isn’t the same as a reader’s experience when they read the poetry. I produce bad poetry sometimes for something good to come from it.

EC: What was your experience like when your poetry was published?

SH: I am very happy to be notified, but I don’t read my poems when they get published. Instead, I start thinking about the next poem — focus on what I want to write next or my next project. I am glad it makes my family and friends happy, but I move on to the next goal always.

This experience is exciting in two ways — seeing my poetry on the shelf in my favorite bookstore and buying the book for my family. I think of my poems, once their out in the world, as my fruits of labors and I am glad they have value to someone else.

EC: Tell me about your poem “Edges” and how it came about.

SH: My poem, “Edges,” deals with body image concerns from my younger years. I try to honestly portray that experience. But the thing about topics like body image concerns that I notice when I read fiction or poetry is that no matter what the writer’s intending meaning, the poem might have a negative effect on the reader, especially if they are suffering from a body image concern of their own.

I can remember reading a book where a character has an eating disorder, and no matter what the meaning behind the portrayal is, the story kind of makes you feel like you should have one, too. I know there is that danger in writing about the subject, which I don’t think by any means indicates that people shouldn’t write about body image concerns because honest portrayals are important.

I follow this idea of making the body image through to recovery. So, I often use flower and seasonal imagery between winter and spring in my poem. Then at the end, when the speaker is supposedly eating again — the imagery is spring and warmth with beautiful flowers.

I try to follow that idea with a very aesthetically beautiful portrayal of recovery. Making the poem go from a negative place in a character’s life to a recovery place is the goal.