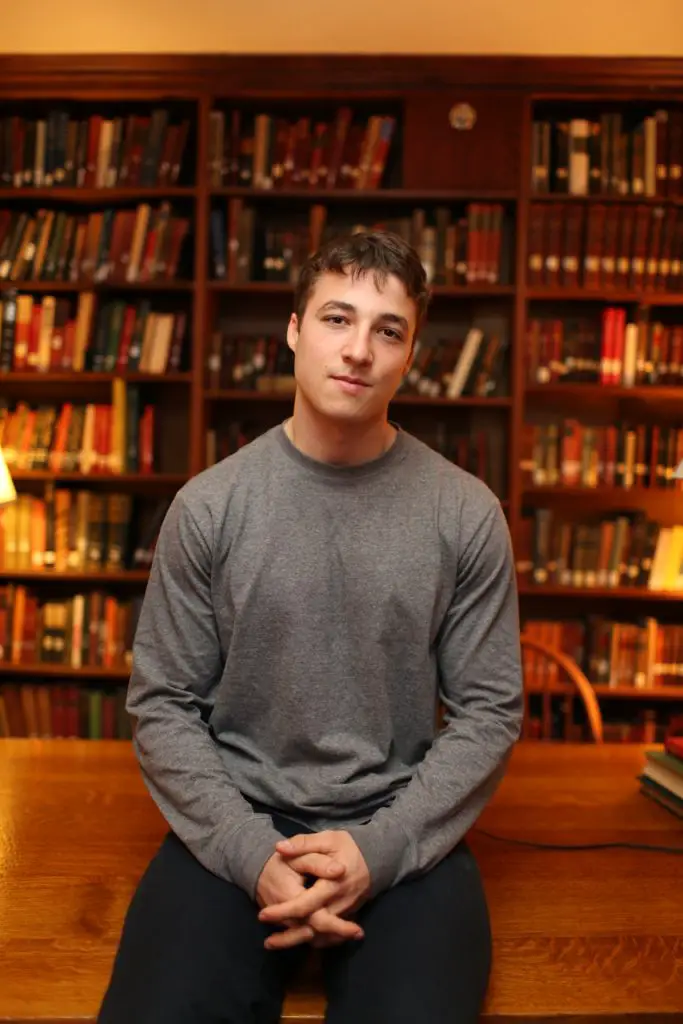

Imagine having, at your fingertips, for free, everything you need to know about college applications: That’s the goal of the Fair Opportunity Project, created by Harvard seniors Cole Scanlon and Luke Heine.

Heine and Scanlon created the Fair Opportunity Project, a guidebook with advice on the college application process, with the intent of giving high school students across the country fair and equal access to any and all available college resources.

Since it first went out in August 2016, the guide has since reached millions of underserved students, been translated into Spanish and Mandarin and helped restore parity to the economically asymmetric world of college admissions. I was able to speak with Heine and Scanlon about the Fair Opportunity Project and the larger task of leveling the academic playing field.

Joiya Reid: How did you guys meet and what’s your story?

Luke Heine: I had taken the semester off to work on the Midwest Information Parity Project, which was essentially a very early stab at creating what Fair Opportunity Project is today. In the process, I reached out to some rural high school counselors and, in a way similar to Fair Opportunity Project, sent a college guide that we wrote to about nine Midwestern states and got really great feedback.

After I came back to Harvard fall semester, I knew that Cole was really interested in education, so we met up and said, “You know, there are a lot of improvements we can make on this guide to turn it into something that can impact a lot more students.” We talked about it in the dining hall and then began working on what is today called Fair Opportunity Project.

JR: So the guide is not solely constructed by you guys, correct?

LH: Correct. The proto-guide, which was the Midwestern guide, was written using the feedback of about two hundred rural high school counselors, which came from a form that I sent out asking them where their students were having difficulty applying to college. I received their input, wrote this proto-guide and then sent it out to these counselors again to be reviewed.

Then, after going through this review process, I sent it out to these students. The following year, when Cole and I really started taking this on, we sent it out to an editorial team of fourteen student editors from around the country because we wanted to get a wide perspective and editorial review on the guide.

We received input from the editors, used it to tune up the guide and then started sending it to admissions committees. After that, we created a mentorship team that has since been really instructive in making sure that we provide high-quality college application information.

The nice thing about this is that Cole and I both approached the project with a mindset of constantly receiving feedback and improving the system. We have a feedback link on every guide that we send out, in addition to the one on our website, just so that we can hear from counselors, teachers and students on how to continually make it better.

JR: This guide is very highly marketed toward public schools. Is that because you think that public schools lack access to the resources that private schools have?

Cole Scanlon: First, we’ve made the guide extremely accessible so that anyone can download and use it; we’ve gotten awesome responses and feedback from private schools, charter schools and various private institutions across the country.

But, when looking at the data and identifying the geographic areas in which students would benefit the most from this — i.e. the pockets in which students are most deprived of this sort of information — we realized it’s concentrated one, in public schools, but two, specifically, in the rural South and rural Midwest.

In addition to socioeconomic differences in areas, we also encountered other geographic nuances. For example, when we first sent out the guide to fifty-seven thousand public schools, we got a lot of emails from California and Florida requesting a Spanish version of the guide.

That’s something we didn’t have at the moment and, to be honest, we didn’t really consider. When we realized there was this need, Philip Alfano, the superintendent of Paterson Joint Unified School District in California, offered to fund our guide to be translated into Spanish. He then sent it back to us, and we sent it out to all the schools that wanted it.

JR: How have your previous work experiences, as an intern at the World Bank and as a U.S. delegate for the World Internet Conference, helped you guys in creating advice for this college guide?

LH: More important than our professional experiences is our background of getting into a school like Harvard. I grew up in a rural town in northern Minnesota, and the last kids who had gone to Harvard from a school like mine had gone thirty years ago. So when I was a sophomore, no one really thought about the Ivy League — really the farthest you would go would be Madison, to the University of Wisconsin.

For me though, my parents were very clear that I would pay for my own education, so, only after finding out about the existence of college applications and financial aid after talking to a guy in a take-out line, I started looking at financial aid programs.

Later, after finding out that you could study for the ACT, I got into Harvard, but if I were to roll the dice 99 other times, I probably wouldn’t be in this school. That’s why, after getting into this kind of position, the agency was definitely on us to make sure that there was an easier, more streamlined, more accessible process for other students down the road.

That then is what motivates the application of tech to this sort of deal, to see how we can have massive impact. Cole and I, we’re both big fans of altruism and think about how we can live lives that have the largest impact on others.

This was a way that we could, with a very small team, impact what might now be up to a million students, and I think that’s an amazing story: that you can impact so many kids from a dorm room, or, like when I started it, in my boxers in my basement in Minnesota. As college students, I think that it’s so important to never forget that with this education comes a responsibility to help others.

CS: Both of our professional experiences — in my case, my experience in tech and at the World Bank—definitely made us more effective, as it created a network of students and advisors who could give us mentorship. But second, to Luke’s point, perhaps the most important part was our personal backgrounds. Although different, they are similar in that we both feel extremely lucky to have the opportunities we have and think that luck played a big role in them.

I went to a public urban school in Miami as a low-income student. Although the average ratio of students to counselors in public schools is about four hundred to one, in my case it was eight hundred fifty to one. So students, some of whom didn’t speak English, got very little advice in terms of how to fill out the complicated financial aid forms or write a college essay. As a result, our experiences made us more eager to scale the project and find how it could serve other students.

JR: Where do you believe high schools fail in terms of preparing students for college?

CS: I think a lot of it isn’t on the school level; the funds are just set up so that schools can’t afford many college counselors. In both of our experiences, we were really proud of the people on the school level and the work that they were doing. So, our resources are by no way a means to supplement what people on the ground, like counselors, provide; they’re only meant to complement and enhance what they’re able to provide.

LH: Unfortunately, there is a lot of interest and money invested in keeping this space asymmetric, keeping the application process such that you can only find out about certain things if you pay someone. In particular, there are a lot of college consultant companies right now that do very well charging families, much of which is done on the backs of anxiety, people feeling unsure about the process.

So, just because the space has become so competitive, it’s unrealistic to think that a town in Nebraska would have all the same information that maybe Greenwich or Cupertino do, where there’s all this money being poured into the question of: “How do we get the best information to our students so they can put their best foot forward?” That’s why we want to take some of the pressure off of the market and say, “Look, our resource is forever free. All the best information on this entire process is free.”

We see it almost as a human right, in that this information dictates so much of the rest of their lives. I was in China this summer, and I was asked by a student who was familiar with Fair Opportunity Project, “Don’t you know you’re putting a lot of college consultants out of business?” I said, “Yeah, absolutely.” This information is free and it should be free for students; that’s what we believe.

JR: So would the idea be to eventually get rid of college consultant services that require students to pay money?

CS: Exactly — we want to flip the table on the whole college consultant factor and, honestly, I think that we’ve made awesome progress on that. In fact, when we sent out the guide, some college consultants actually emailed us to see if they could use it for their services.

All of our resources of course are free; they can be printed and shared for free, so we can’t police people in terms of other people charging to use our stuff, but in that case we did say no. We just said, “Make this available for your students.” The whole goal of Fair Opportunity Project has always been to make this information free and accessible.

JR: The idea of continuing this business without making a profit is kind of crazy. How do you finance your efforts?

LH: We have a couple different models. First, because we’re so intent on flipping an industry that is fueled by anxiety, people and funders really respond to that. Beyond that, we are also playing with a couple different ideas for keeping it sustainable, because we’re in this for the long run.

One thing that we’ve done is talk with a couple of institutions to get sponsorship, in terms of providing ways to pay off student loans, ways to finance and ways to think about what it means to be fiscally responsible after school because, while college traditionally is a four-year commitment, sometimes it can be a twenty-year commitment depending on how those loans are financed.

We’re also experimenting with some corporate partnerships, such as bringing in sponsored content that would be a companion guide to the original guide. Finally, another idea we’re toying around with is a way to help counselors better understand their students by providing modular surveys, which would mean releasing a tool that can help counselors assess how their students are doing compared to students in other districts in a more granular way than currently exists.

JR: In terms of your knowledge of financial aid and the college application process, what gives your program its credibility?

CS: That’s something we’ve had to address directly in sending our guide out to educators, because they need to trust us before forwarding these resources to their students.

First, I think one of the reasons why we’ve gained their confidence so quickly is because the quality is pretty clear in terms of the information that’s provided, the tone in which it’s communicated and the thoroughness with which we created the guide. Second, if you look at our advisors list, that speaks to our credibility as well. The people on our advising team have contributed significantly to the guide and have given some awesome feedback.

LH: I think it also speaks volumes that college consultants are trying to use our guide; if that isn’t a good indication of its quality, then I don’t know what is. It’s also been reviewed down to the comma, and we have America’s top education non-profits serving on our advisory board.

The best thing about this is that, while this is great in terms of establishing credibility, we see the responses we get from counselors and teachers, the true experts in the field who have the job day in and day out, taking this information and giving it to students. There can be a lot of hype about it or whatever, but the Fair Opportunity Project works.