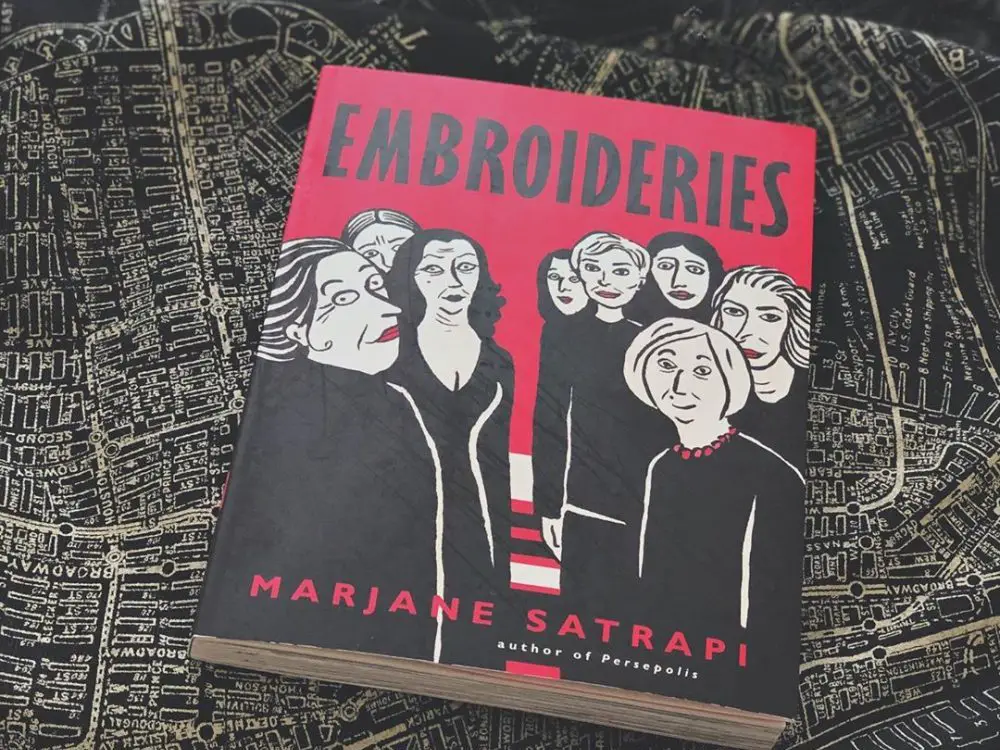

I was introduced to Marjane Satrapi in high school by my enthusiastic (and to this day) favorite English teacher. We were assigned to read her autobiographical graphic novel “Persepolis” and I instantly fell in love. So of course, I had to read the sequel, “Persepolis 2,” and “Embroideries.”

What makes Satrapi’s story so relevant was that she was born in Rasht, Iran, in 1969. As anyone who knows about Iranian and many Middle Eastern countries’ cultures, calling it a male-dominated world is an understatement. It’s easy to glorify the idea of feminism (or womanism) in places like the United States and the United Kingdom; however, in countries such as Iran, traditional values weigh heavily in society and are a lot tougher to break away from.

While we in America are fighting the gender wage gap and the repealing of abortion rights, these women are still fighting for the right to not wear the veil, and they only recently earned the right to drive. I am not downplaying the importance of wage gaps and abortions, I just want to point out there are places that have it so much worse, and as sisters, we shouldn’t forget the ones who don’t have the rights that we already do.

“Embroideries” was published in 2003. The feminist movement started much earlier of course, but it didn’t necessarily become mainstream until the ’70s. (FX’s “Mrs. America” is a great show to binge if you want to learn more.) Although it’s not necessarily documented as thoroughly as in America, feminism in Iran still exists. However, due to a society that favors men, it’s very rarely discussed, and women only really get to talk about it when they are out of the country.

As a womanist, the reason why I find “Embroideries” so powerful is that it portrays these women’s strength, instead of the expectation of weakness. In Iran, women can get thrown into jail for not wearing the hijab. There are physical consequences for the basic human right to have a choice in clothing, which is ridiculous.

In March 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini rose to power, and his Islamic Revolution brought on the chauvinistic regime that forced these women to wear the veil. While Iranian feminists are not fighting to completely eradicate the veil — it holds a symbolic place in the culture — they do want the choice to wear it. This is similar to the fight to preserve abortion rights in the United States; it’s about choice.

Despite “Embroideries” being published almost two decades ago, it is still very relevant to today’s feminist issues. “I realized Satrapi’s little comic had taken on a new meaning: as an embodiment of certain principles of the #MeToo movement. … [It could] have been written today as a paean to the power of women sharing their stories,” said LitHub’s Gabrielle Bellot, a global literature professor who has used “Embroideries” to analyze the depictions of Iran, sexuality, the cult of virginity and the use of artistic perspective as its own interpretational device.

The story starts with Satrapi as an adult, finishing up dinner with some family and family friends. Like many in traditional Iranian culture, men and women retire to different rooms. There they talk about life, love, motherhood, families, the regime and, most of all, sex. Reading this book was very liberating considering that these women are much older than me and even my parents, yet they were so comfortable talking about their views on sex and marriage. They told stories of themselves, of ones they knew and loved, and provided opinions that can be seen as universal lessons for all women.

One of the first stories told is from Satrapi’s grandmother, first seen in “Persepolis,” who is a very hilarious and progressive lady. She proudly mentions that she was married three times, which is admirable, because even in America, many women find that reprehensible — as if the woman is at fault, while the men rarely get blamed. The women in my family are very religious so it was interesting to compare how liberal Satrapi is with her culture and values.

She tells a story of a woman she knew who lost her virginity to her lover while engaged to another man. Traditionally virginity has been a prized gift no matter the culture. It represents purity, and the notion was once you lost your virginity, you were damaged goods.

The grandmother tells an anecdote of a friend who was advised to use a razor the night of their honeymoon to cut herself after sex, to imitate the after-effects of a hymen breaking. The friend was handed a razor and told, “He’ll be proud of his virility and you’ll keep your honor intact.” Unfortunately, instead of cutting herself, she cut her husband in the testicle. Luckily, the shame of being cut by a woman was worse than the shame of not being a virgin, and dishonor didn’t befall the woman.

One of Satrapi’s aunts claims that she has never seen a penis, despite being married for years and having children. She says it’s because she allows her husband to have more control during sex. It’s ironic because in America, children are often exposed to such things early; even before the internet, there were magazines like Playboy always lying around in either your or your friend’s homes. It highlights the cultural differences when an older woman has yet to see a body part of her own husband, yet children four times younger than her have probably already seen the opposite sex’s anatomy.

Another prominent moment in “Embroideries” is when another aunt of Satrapi’s stands up for mistresses. After being married at 13 years old to a 69-year-old man, she became a minister’s mistress. She claims that “It was perfect.” Her argument? Wives have to deal with the husband’s feelings, their dirty laundry, tantrums, bad moods, bad breath, and she even mentions something about hemorrhoids. Meanwhile with mistresses, the men usually only want to have a good time, they always look good, smell good and are in good spirits.

Now, I’m not endorsing infidelity; however, this demonstrates how this story breaks down the preconceptions of Iranian women — especially women of their age. Granted, mistresses have been around since the beginning of marriage and sex, yet when it comes to the idea of Iranian women, because of their conservative attire, I doubt many people expect them to entertain such thoughts. To this day, the book always reminds me to never judge a book by its cover. This story humanizes these women and reminds the world no one is exempt from such human subjects.

Initially, I didn’t understand why the book was called “Embroideries” when there were no signs of sewing or needles and thread in the story. It wasn’t until reading over the end that I realized why it was named the way it was. “The stories are mostly bawdy but devastating. The book’s title refers to surgery, ‘the full embroidery’, to reinstate a woman’s virginity,” said Samantha Ellis from The Guardian. Imagine fearing your husband finding out that you’re not a virgin so much so that you go to have surgery to close up your vagina.

In the graphic novel, Satrapi’s grandmother states: “That’s life! Sometimes you’re on the horse’s back and sometimes it’s the horse that’s on your back.” Despite circumstances out of their control, these women still choose to live their lives to the best of their abilities. They don’t let discouragement stop them or hinder their happiness. They know certain aspects can be unfair, however instead of dwelling on it, they put their focus on the things that they can control and change.

As an American womanist (which is a whole other article) I am thankful to those before me that fought for the rights that I have today. Little things such as choosing your own clothing can be taken for granted when others around the world don’t get a choice.

“When the snake gets old … the frog gets him by the balls,” says the Grandpa (Grandma’s third husband) when he tries to interject himself into the women’s conversation. Grandma authoritatively shoos him out of the room and he huffs in defeat. Even if society has them down throughout it all, in the end, the women do prevail.