They’re gray. They’re blocky. They’re ugly. They are the massive buildings of unpolished concrete and rebar that litter America’s hallowed halls of learning. These dystopian slabs are the imposing monuments of the brutalist style of architecture, and for a short time, brutalism was considered a promising glimpse into the future of public spaces.

The Great War left many European cities in ruins. Villages and towns in the warpath were pounded flat with artillery, while the great cities that remained untouched saw their streets and buildings stripped for excess masonry and metal.

In those desperate times, many urban planners and artists developed a disgust with the excesses of traditional construction. Other countries, especially those in Eastern Europe, needed to construct reliable buildings fast as they quickly industrialized. The old way of building wasn’t cutting it anymore, and a replacement for traditional architecture was sorely needed.

This was the beginning of a new dogma in architectural theory: “form follows function” — a radical idea inspired by a quote from the great architect Louis Sullivan. Sullivan’s original theory held that form should not interfere with function. He did not think it needed to be eliminated altogether, however; after all, he was known for his appreciation of Celtic embroideries in his buildings.

The architectural community didn’t care for his praxis, however, and extrapolated his theories into principles like architectural Functionalism, which held that a building’s aesthetics should be informed only by its purpose.

Brutalism had its start here, in the Functionalist wave. It was the brainchild of a group of English architects and academics inspired by the bare and simplistic style of “Funkie” houses in Uppsala, Sweden. These architects were captivated by the houses’ plain geometries and lack of ornamentation — features that stood out among the city’s intricate neoclassical architecture and vibrantly-colored row houses. In these quaint dwellings, the architects saw a promise for a new, more honest form of pragmatic architectural expression that would herald the modern age.

Alison and Peter Smithon were the first architects to put this new idea into practice in the 1950s. First, they constructed a small public school in Norfolk, England, and they followed that with corporate and public buildings, most notably the Economist office in London. The Smithons designed their buildings around a personal philosophy that their work was an “ethic, not an aesthetic,” those ethics being a functionality over all, as a reflection of postwar English values. As such, Smithon buildings were left bare of ornamentation, made of raw concrete and glass and intended for abuse.

The Smithons saw their work as a canvas for life, a place where occupants could feel free to live and clutter without feeling shamed for potentially ruining a grandiose environment with the mundane wear of working life.

The prominent French architect Le Corbusier was a prominent user of concrete. He called this style “Beton Brut” — French for “exposed concrete.” Architecture critic Reyner Banham later re-coined the phrase as “brutalism,” which was a pun meant to mock the bare and harsh stylings of the buildings that he saw as bereft of humanity.

The name was embraced by the Smithons and their contemporaries. Even for its time, brutalism was not well-received by critics and the public, but popular opinion did little to dissuade the construction of new brutalist buildings, and the movement spread like wildfire throughout Europe.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BdDeN3QhhSK/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

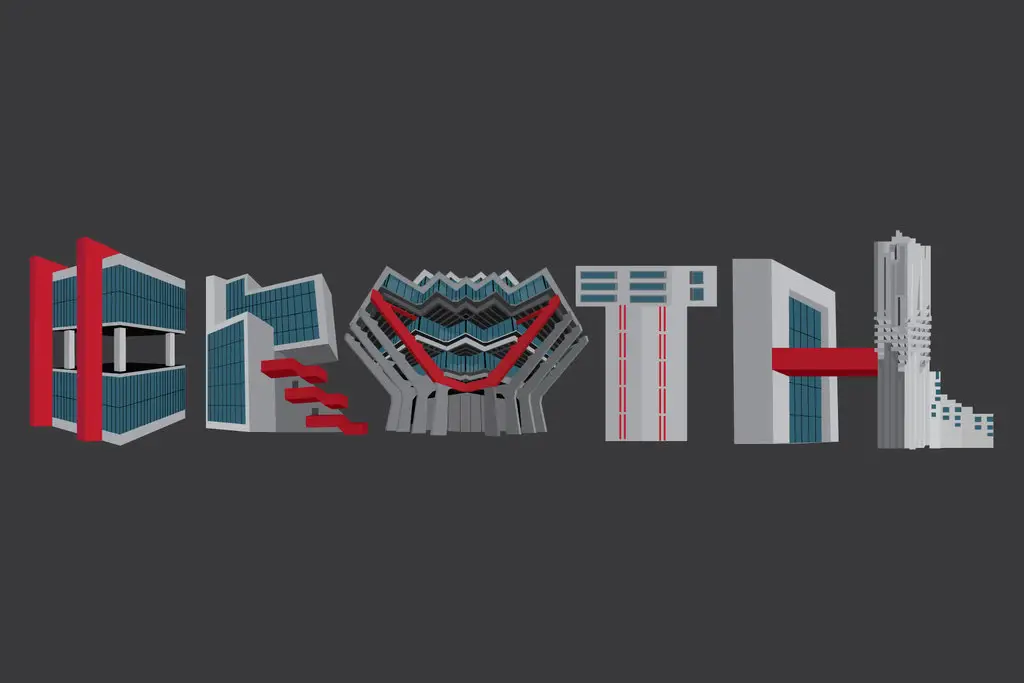

Brutalism did have its advantages over other contemporary styles. The poured and treated concrete basis of brutalist buildings was plentiful, strong and moldable. Unlike traditional architecture that had to be built brick by brick, whole portions of brutalist buildings could be cast like metal then assembled in construction. In contrast to its minimalist roots, this allowed for brutalist buildings to become truly massive and elaborate in form without the need for artisans and masons.

Architects were also drawn to brutalism’s egalitarian vision. To them, it offered a chance to build affordable housing and public spaces free of pomp, while pragmatic city planners and money-conscious institutions fell in love with brutalism’s cost-effective solution to large-scale projects.

America’s cosmopolitan universities were among the first U.S. institutions to adopt brutalism, with Yale’s Art House extensions predating many British structures after finishing construction in 1949. As it was a revered Ivy League school, Yale’s early adoption of brutalist architecture made the movement vogue in U.S. universities, and other schools started building new brutalist structures wholesale. The quick adoption of brutalism by American universities was spurred on by many of the same factors that made it such a popular movement in Europe.

The baby boom and miracle economy of the late ’40s and ’50s had produced a much larger population of potential students than had ever existed before in American history. Few universities had the facilities to meet the demand, and fewer had the housing — before the ’50s, students primarily resided off campus. The dorms and residence halls that did exist weren’t nearly big or robust enough to accommodate the thousands of new students that the coming decades would bring. Brutalism, with its ethos of building cost-effective and large public buildings, provided the perfect solution to this crisis.

Besides offering some minor extensions and cheap housing, brutalism became the go-to style for the wave of new universities opening their doors to the flood of new students. There was a sentiment that to compete with established schools and the new competition, a university had to have a robust and unique campus. To this end, brutalism was used as the go-to architectural style for designing new stadiums, cafeterias, performing art centers and libraries. If your school was founded in the ’60s or ’70s, odds are that most of its facilities are brutalist in design.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B9ALUFlB6e-/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

For as dramatic and ever-present as the movement was, brutalism was a short-lived phenomenon. It never reached the utopian heights its founders had intended, and rather than empowering the masses with a sense of egalitarian space, it garnered the opposite sentiment. No amount of ethical philosophy or whimsical shapes could hide the inherent hardness and intimidating nature of brutalist buildings.

Worse still, with their popularity in Europe’s Eastern Bloc and U.S. government-operated facilities, the buildings were forever associated with authoritarianism and repressive institutions. Thanks to the backlash and intimidating aura of many of the buildings, a popular urban myth began to circulate around American universities of the ’70s — that their schools’ brutalist buildings were meant to suppress riots and nuclear bombs.

Brutalism was also a victim of the concrete that composed it. Once thought to be a miracle building material, over the course of a few decades, it became inarguable that concrete ages disastrously. Sickly discolorations of black and brown marred the once utopian uniformity of the gray and white material, while its proneness to cracking and weathering betrayed the timeless sturdiness of brutalist monuments. Far from being associated with a bright future, brutalism became a symbol for urban decay and dystopianism in popular culture.

The biggest blow to the movement, by far, was the discovery that brutalist buildings actually cost a lot to run — far more than just about every other conventional building. Though cheap to build, the thick concrete and glass construction inherent in the design provides poor insulation, and it actively thwarts attempts for modernization and renovation.

The many campuses that eagerly filled their grounds with the buildings were left with reviled, giant boxes that were expensive to run, expensive to expand and expensive to tear down. With few buyers of the buildings and the failure of their central ethos of pragmatic functionalism taken out from underneath them, the brutalist school of architecture and its die-hard adherents quietly drifted to other schools of design.

Most great works of public brutalism were knocked down in the ’80s and ’90s, usually replaced with clean modern designs or classical revivalist styles that would have driven the Smithons to tears. It is on college campuses that the now endangered style continues to hold strong, as not many schools can afford the exorbitant cost or time investment associated with tearing down these formidable buildings — these ugly, gray block monuments to the future that never was.